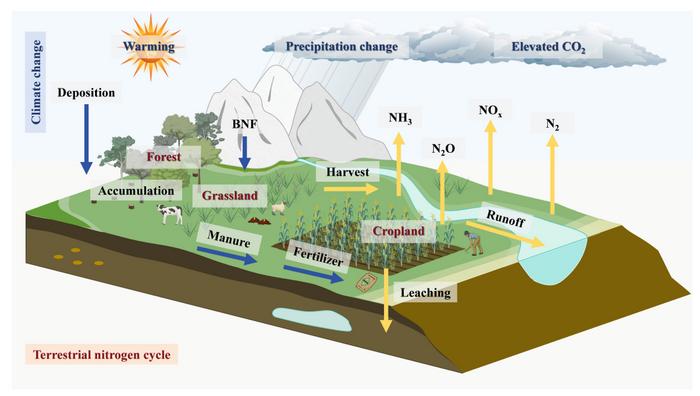

Climate change is widely known for rising temperatures and shifting rainfall or intensifying winters or summers, but scientists say it is also transforming something far less visible and just as critical. It’s transforming the global nitrogen cycle.

New research shows that climate-driven changes in how nitrogen moves through croplands, forests, and grasslands could have major consequences for food security, water quality, biodiversity, and climate policy.

Nitrogen is a basic building block of proteins and DNA, and healthy ecosystems depend on a careful balance of nitrogen in soils, plants, and microbes. When this balance is disrupted, agricultural yields can decline, rivers can fill with algae, and more greenhouse gases can be released into the atmosphere.

“In a warming world, nitrogen is becoming a make-or-break factor for both food security and environmental health,” said lead author Miao Zheng of Zhejiang University. “Our study shows that climate change is reshaping nitrogen cycles in ways that can either support sustainable development or push ecosystems beyond critical thresholds.”

A farmer measures nitrogen level in his paddy field in Karnal, Haryana. (Photo: Reuters)

WHAT WAS EXAMINED AND FOUND?

To reach the alarming conclusion, the study reviewed 30 years of field experiments and global model simulations to assess how three major climate drivers are altering nitrogen flows worldwide.

These three major drivers were rising carbon dioxide, higher temperatures, and changing rainfall patterns.

By combining hundreds of local studies, the researchers mapped how nitrogen inputs, plant uptake, harvest, losses, and long-term storage respond across different ecosystems and regions.

One of the key findings of the study was that higher carbon dioxide levels can increase plant growth.

Forests and grasslands show yield gains of 10 to 27 percent, while major crops such as wheat, rice, maize and soybean see increases of around 21 percent. However, the review warned that this growth often comes with a decline in nitrogen content.

“More calories do not automatically mean better nutrition,” said co-author Baojing Gu. “We may be harvesting more biomass but with less nitrogen per unit, which matters for both human diets and livestock feed.”

Impacts of climate change on global terrestrial nitrogen cycles. (Photo: EurekAlert)

CLIMATE CHANGE DRIVING TREND

Rising temperatures generally have more damaging effects.

Warming reduces yields of key crops, particularly maize in tropical and dry regions, while increasing nitrogen losses into the air and water.

Warmer soils stimulate microbes, releasing more ammonia and nitrous oxide and allowing nitrates to leach into rivers and groundwater.

Rainfall changes add further complexity.

Extra rain can boost growth in dry regions, but intense or frequent rainfall increases nitrogen runoff, worsening water pollution and raising the risk of algal blooms.

Storm runoff from a recent rainstorm in Southern California. (Photo: Reuters)

The study concluded that climate change is amplifying inequalities, with developing regions facing the greatest risks to food production and environmental health.

The authors called for integrated nitrogen management that connects fertiliser use, water management, climate action, and biodiversity protection.

“We need to move beyond treating nitrogen as just a farm input and start governing it as a global commons,” said Zheng. “If we manage nitrogen wisely under climate change, we can support zero hunger, protect clean water, and limit greenhouse gas emissions at the same time.”

– Ends