Nearly two decades after Adolphus Greely was wounded three times during the Civil War, he accepted a much more perilous mission.

In 1881, the United States partnered with 10 other countries to develop a series of circumpolar stations to study the Arctic. Part of the first International Polar Year, the expeditions sought to learn more about a region of the world widely considered a “sheer blank” at the time. Greely was placed in charge of the northernmost station off Lake Franklin Bay in Greenland, roughly 500 miles from the North Pole.

Greely, who fought at Antietam and Fredericksburg, saw firsthand some of the worst things a battlefield has to offer. Still, it couldn’t prepare him for the Arctic, where he and the 24 other members of his expedition were stranded for two years. During that period, they endured unbearingly cold conditions, starvation, and desolation as they awaited rescue.

Related: This extreme winter survival course teaches troops how to stay alive in Arctic conditions

“To die is easy; very easy; it is only hard to strive, to endure, to live,” Greely wrote in his journal during the ordeal.

Greely’s words would be proven prophetic. By the time a ship transporting the last remaining members of the Greely expedition arrived in Portsmouth, N.H., on August 1, 1884, only six of the original 25 were still alive, including Greely.

An Expedition that Began with Such Hope

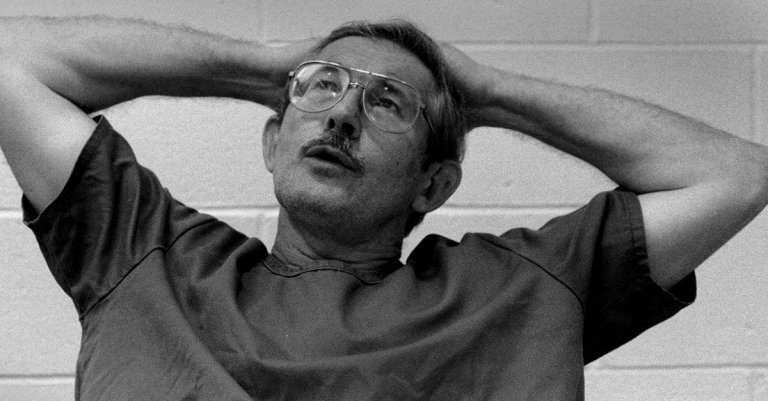

An undated portrait of Civil War veteran and explorer Adolphus Greely. (National Park Service)

An undated portrait of Civil War veteran and explorer Adolphus Greely. (National Park Service)

Born in 1844, Greely was only 17 when Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter. Even though he was under age, he enlisted in the 19th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, and his responsibilities steadily increased as he reportedly rose to become the first volunteer private soldier to reach regular Army general officer rank during the Civil War.

In 1867, Greely joined the U.S. Army Signal Corps, where he learned about telegraphy and meteorology and helped Brig. Gen. Albert Myer, the chief signal officer, to establish the U.S. Weather Bureau. When he learned about the expedition to the Arctic, Greely was eager to be included.

“There was fame to be gained, there was glory to be gained, and he had this very, very strong drive to make himself exceptional so he would be recognized by the military,” author Jim Lotz said in the “Greely Expedition,” a PBS “American Experience” documentary.

The USS Proteus departed St. John’s, Newfoundland, with the expedition team and 350 tons of supplies (enough for three years) aboard in July 1881. When they reached Lake Franklin Bay, they had no idea what they were about to encounter.

Contingency Plans Fail

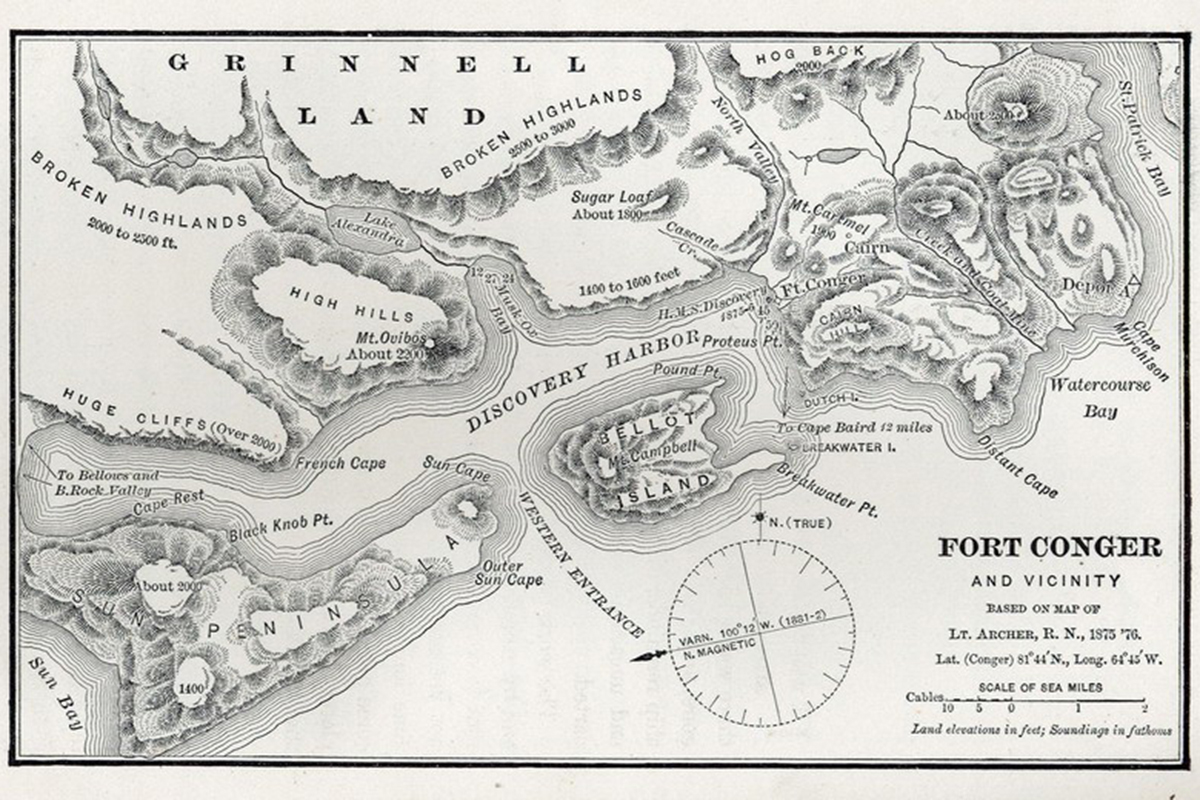

A map of Fort Conger and its vicinity. (CECOM History Archive Collection)

A map of Fort Conger and its vicinity. (CECOM History Archive Collection)

The men constructed a base of operations on Ellesmere Island that they named Fort Conger after a U.S. senator whose fervent support played a pivotal role in the expedition. For the next two years, their daily duties revolved around learning more about the Arctic. They compiled more than 500 around-the-clock observations daily, according to a 2010 article by the U.S. Naval Institute. The data collection fell into various categories: meteorological, tidal, magnetic, and astronomical, among them.

As their work continued, it was always with the knowledge that contingency plans were in place to bring them home. A resupply ship was to arrive at Fort Conger in 1882, with another ship being dispatched the following year to bring them home. Neither vessel made it to Lake Franklin Bay, because ice either crushed them or prevented their advance. Other reasons contributed to the plan going awry, including “bureaucracy and half-baked resupply attempts,” according to the U.S. Naval Institute story.

After the first ship didn’t reach Fort Conger, the disappointment was a tremendous blow to the team’s collective psyche. They were isolated, and the mental toll of not having contact with the outside world was agonizing. Even though they dutifully continued their work, their morale suffered.

When no relief ship again failed to appear in 1883, Greely made a fateful decision: They would travel 250 miles to the south to a previously agreed-upon site, Cape Sabine, where they would await rescue. Although the decision to leave the relative security of Fort Conger almost resulted in mutiny, according to the PBS documentary, the expedition team departed their base in small boats in August 1883. When they arrived at Cape Sabine, their disappointment only intensified after they found a smaller than expected cache of supplies.

“We have been lured here to our destruction,” Greely recounted in his journal. “…It drives me almost insane to face the future.”

Death Ravages Greely’s Men

A glacier in northern Greenland is shown from the view of NASA’s P-3B aircraft on May 3, 2012. (NASA/Michael Studinger) Michael Studinger

A glacier in northern Greenland is shown from the view of NASA’s P-3B aircraft on May 3, 2012. (NASA/Michael Studinger) Michael Studinger

Crammed into a small shelter, Greely rationed the men’s food in hopes that a two months’ supply could last until they were hopefully rescued. Deprived of an adequate supply of food, the results were tragic. On Jan. 18, 1884, the first expedition member died, according to PBS’ timeline of events. Greely’s team did whatever it could to survive, including eating candle wax, boot soles, and bird droppings, but the odds were insurmountable and more men perished. It was not only their bodies withering away with each passing day; their mental states were deteriorating as well, with one man talking “at times like an infant” as he succumbed to the horrific conditions.

By the time a rescue team arrived in June 1884, only seven men were still alive, their gaunt figures a stark reminder of what they endured. One man died on the trip back to North America, his body weighing only 78 pounds.

While Greely’s team was greeted with a hero’s welcome upon their return, criticism soon followed. There were reports of mismanagement by Greely and, worse, cannibalism among his team, including evidence that flesh from seven corpses had been cut away with knives. Greely denied those allegations, with The New York Times reporting: “As to the eating of human flesh, Lt. Greely stated, with much feeling, that… no act of this sort had been committed by anyone connected with the party.”

Greely was never tried on such charges.

What the Greely Expedition Accomplished

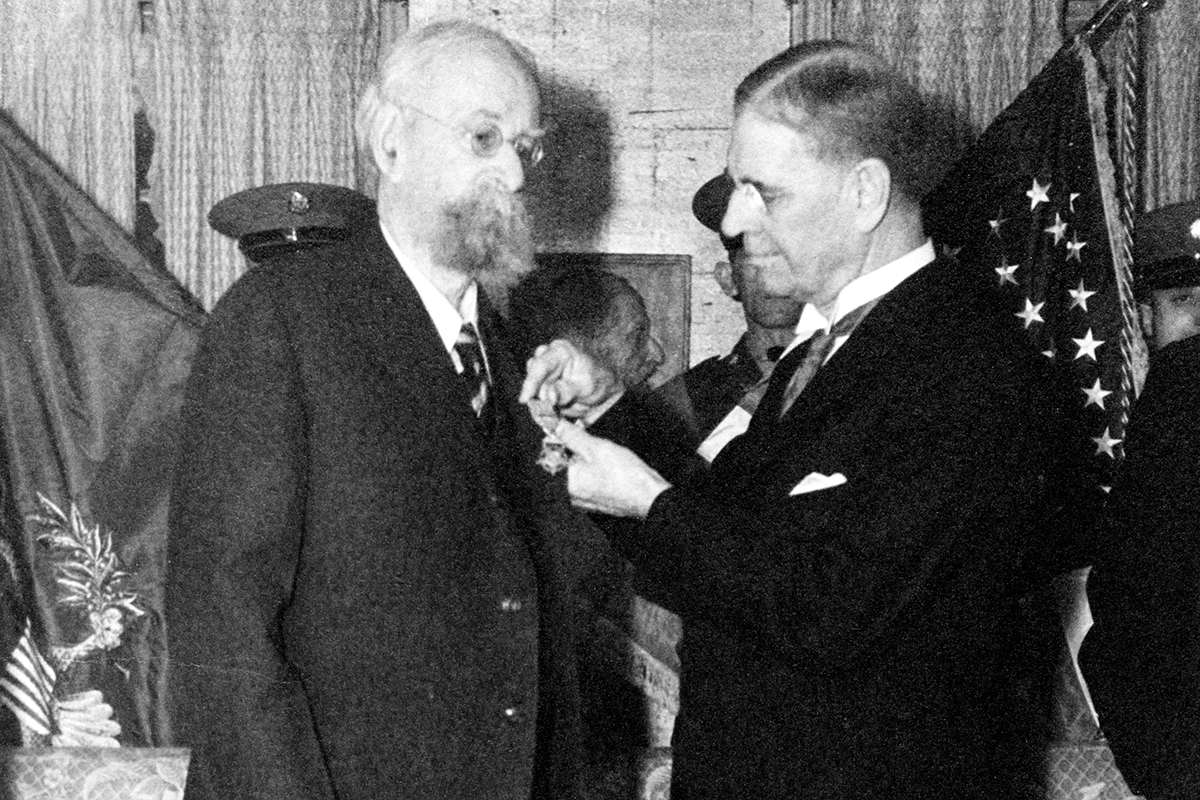

War Secretary George Dern pins the Medal of Honor on Civil War veteran and explorer Adolphus Greely in 1935 for his ‘splendid public service.’ (Library of Congress)

War Secretary George Dern pins the Medal of Honor on Civil War veteran and explorer Adolphus Greely in 1935 for his ‘splendid public service.’ (Library of Congress)

From a purely scientific perspective, what the Greely expedition accomplished was remarkable. His team manned one of 14 international stations that combined to explore more than 6,000 square miles of new terrain. Their hard work advanced the understanding of global warming, as well as providing the U.S. with the distinction of traveling to the farthest northern point on Earth at the time.

Greely went on to become chief signal officer of the Signal Corps, where his innovations led to the introduction of wireless communications, the airplane, and automobile into the Army. He retired from military service in 1908 and received the Medal of Honor for “splendid public service” in 1935, a few months before his death at the age of 91.

Greely is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Don’t Miss the Best of We Are The Mighty

• The only time a Medal of Honor recipient killed another Medal of Honor recipient

• The American mafia teamed up with the Navy to get even with Mussolini

• How the US deleted Venezuela’s air defenses so quickly (and why the real war might be starting)