Economic Note explaining why Canada must resist the temptation to follow the example of the European Union and its AI Act

* * *

This Economic Note was prepared by Pierre Bentata and Nicolas Bouzou, Research Associates at the MEI. The MEI’s Regulation Series aims to examine the often unintended consequences for individuals and businesses of various laws and rules, in contrast with their stated goals.

According to an international study on artificial intelligence conducted in 2025 across 21 countries,(1) Canadians seem aware of the positive impacts that artificial intelligence (AI) could have on productivity and innovation, but remain more worried than the average respondent regarding the risks it represents. The majority of Canadians are first and foremost preoccupied by the risks posed by AI and favour specific regulation, a position shared by a comparable proportion of European respondents. Canada could therefore be tempted to follow the example of the European Union and its AI Act.(2)

However, before going down this regulatory path, Canadians should be aware of its complexity and of the negative consequences it could entail in terms of innovation, the competitive environment, and international competitiveness. They would thus avoid “importing” the errors observed in Europe’s regulation of AI.

Benefits, but Also New Risks

From logistics to finance, e-commerce, agriculture, education, and of course medicine, AI takes the form of specialized systems designed to automate tasks and improve decision-making.(3) Its benefits include time savings, better flow management, and improved services, which lead to substantial productivity gains. The most cautious estimates predict an increase in overall productivity of 0.53% over ten years, while some studies project a gain of 14% for low-skilled “support” workers thanks to large language models (LLMs), another kind of AI.(4)

The EU adopted a regulation aiming to protect health and safety, but also fundamental rights. Despite these good intentions, this regulation of AI is encountering several pitfalls.

It is precisely the introduction of these LLMs (ChatGPT, DeepSeek, Grok, Mistral, Gemini 3), allowing anyone to formulate precise prompts in order to obtain specific responses, which so far constitutes the biggest promise in terms of innovation and the promotion of a competitive environment. These models favour the internalization of tasks that have until now been expensive for businesses—legal advice, accounting, communications—and reduce barriers to entry for certain sectors formerly sheltered by significant fixed costs, which could lead to more intense competition and lower prices. As for their application to health care, it raises the prospect of predictive, personalized medicine.(5)

Yet, the use of AI, whether specialized systems or LLMs, generates certain specific risks. The most obvious is manipulation and social control. This is the case when AI uses biometric data to predict behaviour deemed dangerous or identify individuals in order to alter their judgment using subliminal techniques.(6)

Another risk has to do with the relative autonomy of AI in the case of an accident or damage, whether a road accident caused by an autonomous vehicle, a diagnostic error arrived at by an AI, or a discriminatory hiring process following the automated sorting of candidates.

Finally, LLMs pose a particular risk related to the possibility that someone might misuse them to access protected content, create false information or “deep fakes,”(7) or produce computer viruses or even explosives.(8)

A Source of Legal Uncertainty for Entrepreneurs

Faced with these new risks, governments are tempted to regulate AI. On May 21, 2024, the European Union adopted a regulation aiming to protect health and safety, but also the fundamental rights of European citizens that could be infringed upon by the use of AI systems (including equality, non-discrimination, the protection of personal data, democracy, and environmental protection).(9)

A part of the law came into effect in August 2024. Another part was supposed to come into effect in August 2026, but on November 19, 2025, the European Commission proposed to delay this until the end of 2027, while maintaining its scope. (This proposal must be ratified by the European Parliament and adopted by the member States.)(10)

The European regulation risks restraining innovation and reducing the competitiveness of businesses, all without guaranteeing better protection for citizens.

Despite these good intentions and this delayed implementation, this regulation of AI still weighs on the sector, as it is encountering several pitfalls that deserve to be highlighted and avoided.

Impossibility of quantifying risk

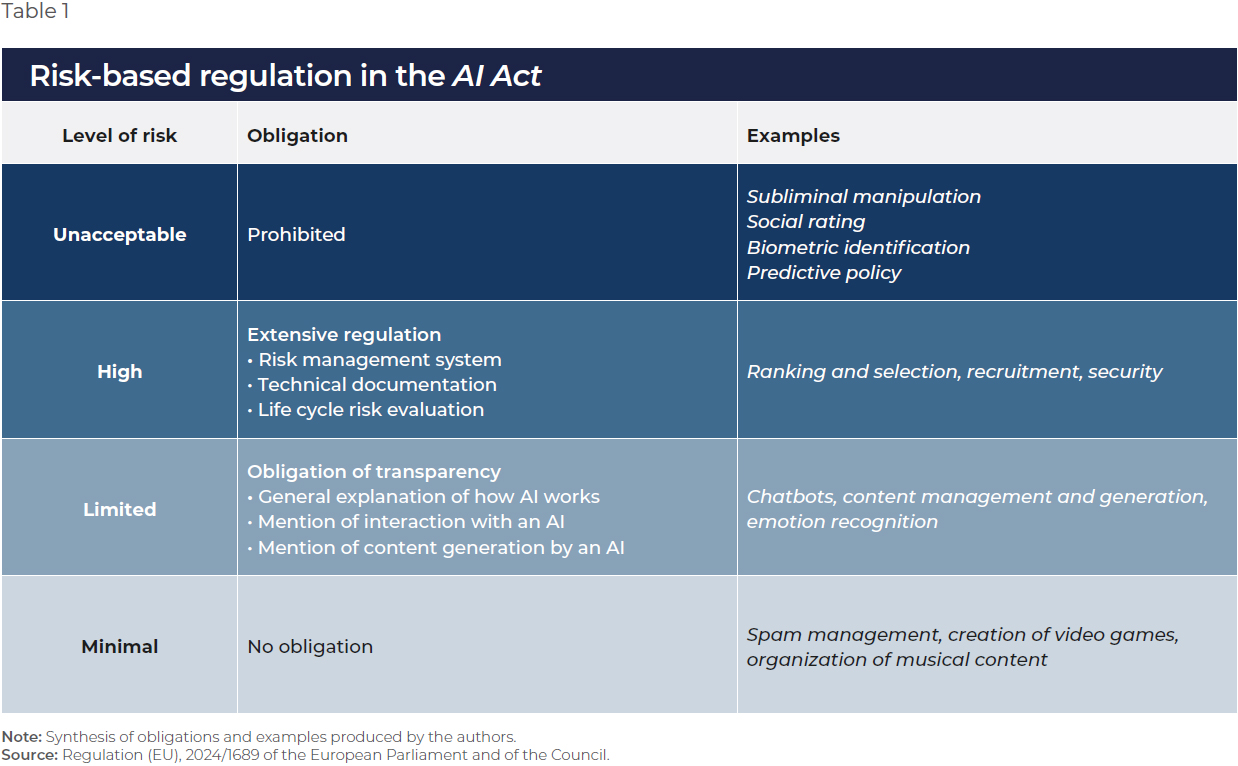

The general idea behind this regulation is to impose obligations upon AI suppliers and deployers based on their product’s presumed risk. As shown in Table 1, four levels of risk are stipulated, from minimal to unacceptable, with specific constraints for each. Intuitively, this approach based on risk makes sense, since it aims to encourage businesses to take appropriate precautions. This is what is done when it comes to health care, the environment, and defective products.

However, the measurement of risk here poses a specific problem, as it is not simply a matter of evaluating material or physical damages, but rather infringements of fundamental rights.(11) In order to comply, suppliers and deployers must estimate the likelihood and the severity of a possible infringement of those rights. Yet, no business is in a position to carry out such a calculation. Indeed, they can neither quantify the impact of such infringement nor determine the probability that it will occur—these elements depending in large part on the way in which the AI will be used.

Rigidity of the new regulation based on economic sector

The AI Act provides a list of the sectors concerned for each level of risk and singles out eight sectors for which the use of AI is by definition considered “high risk.”(12) It thus adds sector-based regulation on top of the risk-based regulation. This can be justified in the sectors mentioned previously where AI can represent a more easily identified unacceptable risk.

For large businesses, the cost of regulatory compliance is relatively easier to absorb, while for a new business, it constitutes a real barrier to entry.

In contrast, for the other categories of risk, this distinction by sector can prove highly problematic, as it is essentially arbitrary, for two main reasons.

First, this rigid sectorial structure imposes very restrictive obligations on all suppliers and deployers of sectors considered “high risk,” such as:

evaluating the AI’s level of risk throughout its life cycle;

creating a risk management system that i) describes all the data used by the AI, ii) analyzes each bias and error, iii) details the solutions adopted, iv) specifies the volume of data required to train the AI, and v) ensures the AI’s accuracy, robustness, and safety.

Concretely, this means that any use of AI in such a “high risk” sector will be saddled with a substantial regulatory cost, and the supplier or deployer could be sanctioned with a fine of up to 15 million euros or 3% of annual global sales (section 99) if it fails to comply with requirements.

Second, this sector-based approach does not take into account the diversity of uses within a given sector. For example, the video game sector is considered “minimal risk,” entailing no regulatory obligation. Yet it is entirely possible to use AI to analyze the behaviours of players in order to elicit addictive reactions that could lead to the purchase of objects and equipment online. In this case, such an AI (in a low-sensitivity sector like video games) would be much more dangerous than an AI used simply to sort résumés by level of schooling, or an AI trained to predict the risk of insured parties having traffic accidents. Nonetheless, the former would be subject to no restrictions, while the other two would have to comply with the most severe regulatory requirements.

Restraining the Sector’s Development

The European regulation risks restraining innovation instead of encouraging it, and reducing the competitiveness of businesses when it comes to AI, all without guaranteeing better protection for citizens.

A barrier to entry for start-ups

The sector-based regulation of “high risk” AI imposes a uniform cost on all players active in or wishing to enter these sectors, which necessarily leads to a distortion of competition to the benefit of the largest corporations.

The impact study published by the European Commission estimates that just implementing the management system described above could cost up to 240,000 euros for a business with a single employee, and up to 401,000 euros for a business with 100 employees,(13) or roughly 60 times more per employee in the first case. Thus, the regulation is like a fixed cost which is much easier to defray when a business has already reached a certain size and has a substantial workforce. In other words, for large businesses, the cost of regulatory compliance is relatively easier to absorb, while for a new business, it constitutes a real barrier to entry.

The AI Act risks bringing about an automatic slowdown in AI development in Europe, leading it to fall further behind the United States.

The AI Act could therefore hurt the AI sector, just as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) hurt the European personal data collection and processing sector.(14) Since coming into effect in 2018, the GDPR has aimed to oversee and anonymize the collection, use, and monetization of personal data by digital players through the imposition of obligations that act like a fixed cost. Early estimates of its economic impact show that it mostly just reduced the sector’s competitive intensity by favouring large platforms, better able to absorb the regulatory costs and provide their partners with guarantees of compliance with all obligations.

In less than five years, more than one in ten companies disappeared—mainly young companies. This allowed large digital companies to increase their market shares(15) and led to a slowdown of innovation in the sector in Europe compared to the United States. Indeed, the number of available apps fell by a third, and the entry rate for new apps plummeted by 47.2%.(16)

A drag on the creation of an AI ecosystem, as Europe falls further behind

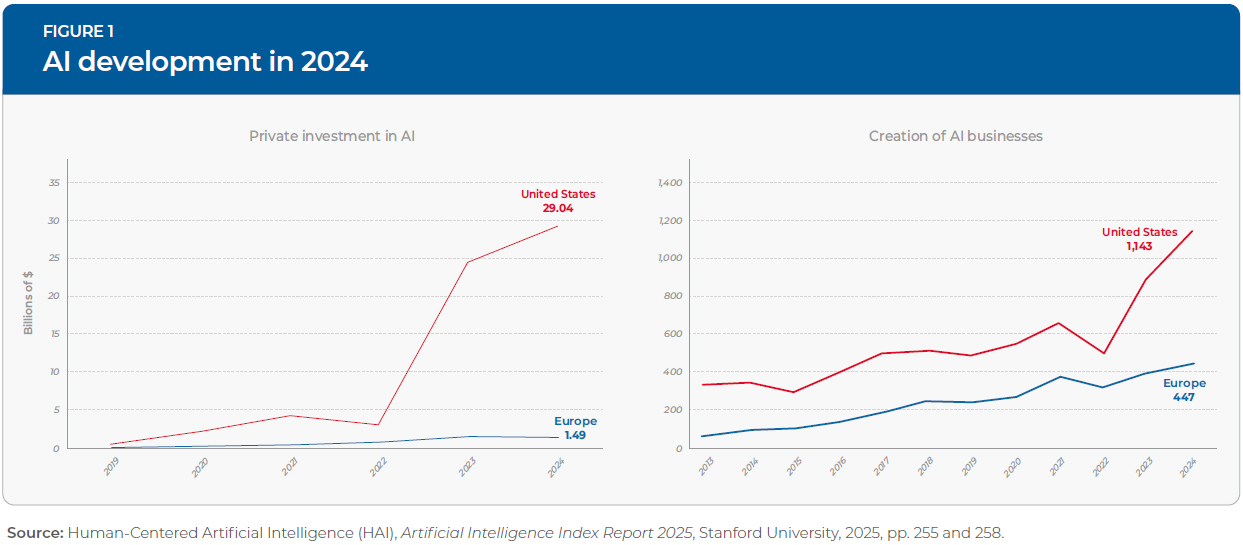

If the AI Act were to have similar effects, the European AI sector would find itself in an even more worrisome situation given that it already lags far behind its American counterpart. As can be seen in Figure 1, since 2022, the creation of AI businesses has increased substantially in the United States, and in 2024 there were almost three times as many as in Europe. At the same time, private investment in AI grew exponentially in the United States, whereas in Europe, it stagnated. Over $29 billion were invested in the U.S. in 2024, almost 20 times the $1.5 billion invested in Europe that year.(17)

The development of a dynamic and competitive digital ecosystem requires substantial investment and the presence of large companies, but also a large number of young companies. By imposing barriers to entry on small businesses and a surcharge on the entire ecosystem, the AI Act risks bringing about an automatic slowdown in AI development in Europe, leading it to fall further behind the United States. This is all the more likely given that digital technologies, with their network effects, provide a competitive advantage to first movers and companies that are able to quickly achieve critical mass.

Conclusion

Before adopting specific AI regulation inspired by the European model, the implementation of which even the European Commission now wants to partially delay until the end of 2027, the Canadian authorities should draw the lessons learned from the AI Act. Three pitfalls in particular should be avoided:

First, it seems unrealistic to force businesses to implement an approach based on the risks to fundamental rights. It would be preferable to opt for regulation based on an AI’s degree of autonomy, with only the less controllable AIs being subject to specific oversight.

Second, a more flexible approach could apply to other AIs by simply extending existing rules of civil liability to the damage they could cause.

Finally, the sharing of risks should include final users, especially in the case of LLMs. Indeed, no LLM producer can foresee everything final users might use it for, and effective regulation should include measures designed to dissuade such users from causing harm.

By following these recommendations, AI oversight could be set up without undermining innovation and the competitive dynamic of the sector.