Thousands of film critics, columnists and student journalists have written at least one piece about the brilliance of director Martin Scorsese. There are few who can see the world so clearly through the dirty and broken windowpane of life — and even fewer who can help others see the same. Your grandfather loved Mean Streets, your father vouches for how great The Goodfellas was, and you probably loved The Wolf of Wall Street, but that film doesn’t exactly fit into the same category as the two above, or does it?

When the prolific director entered into this century, he was doing so on the backs of films like Bringing out the Dead (1999) and Kundun (1997). None of these films were ‘out of the park’ ordeals, but they weren’t necessarily bad films. But films were now changing, and so was the audience. The young rebels who related to Henry Hill or Max Cady had now grown up and were probably lining up to watch The Lion King with their kids. Martin had to change too, but just like everything else in his career, he did it his own way (that’s Paul Anka, by the way, not Frank Sinatra).

Margot Robbie as Naomi Lapaglia. (Photo: IMDb)

Margot Robbie as Naomi Lapaglia. (Photo: IMDb)

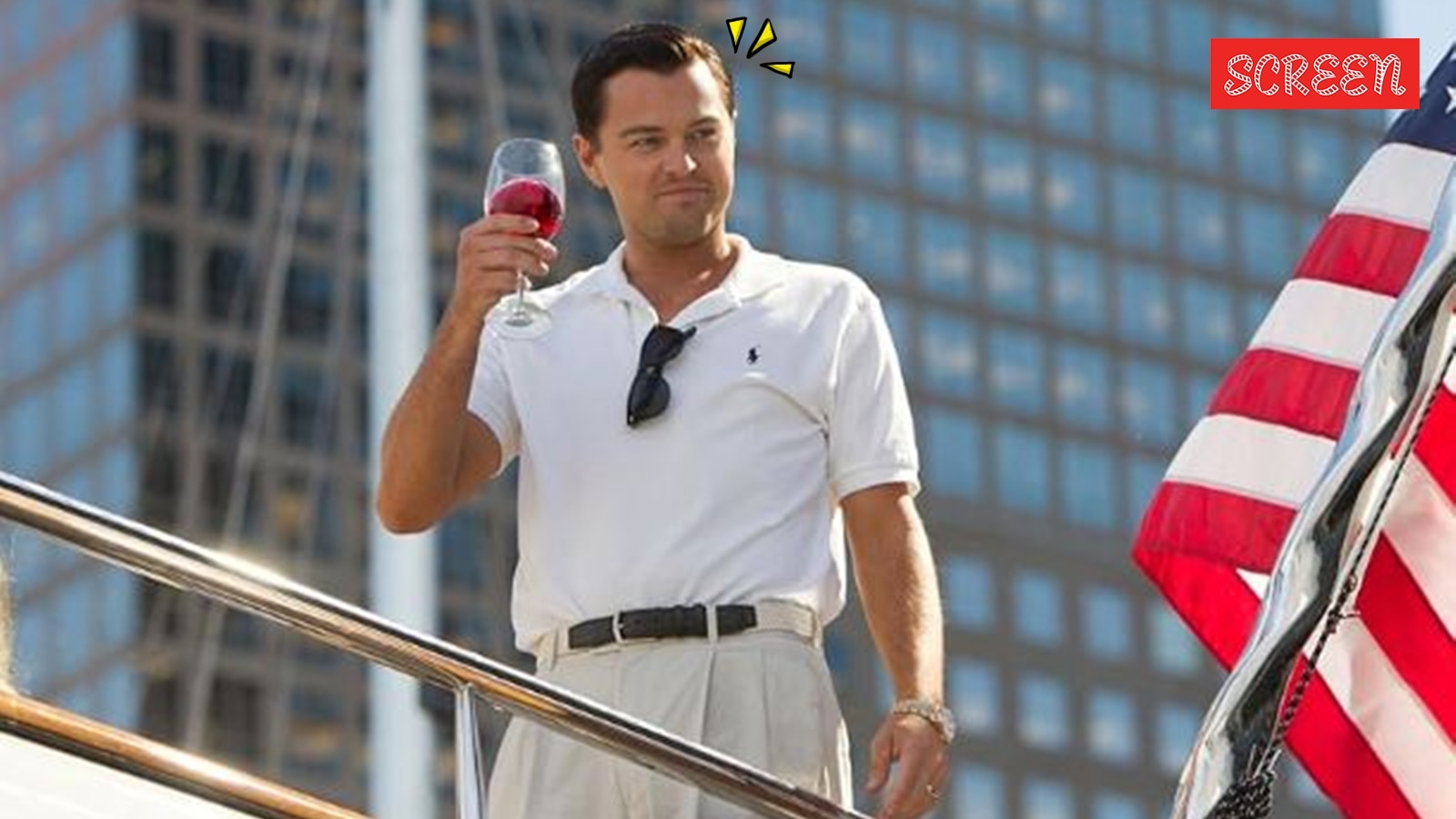

After giving the moviegoers films like The Aviator (2004), The Departed (2006) and Shutter Island (2010), no one saw his collaboration with Leonardo DiCaprio reaching new heights or a parallel plane. Then came The Wolf of Wall Street, which was a culmination of every delinquent character arc that Martin had ever thought of, told with the finesse of a crime drama. The films boasted a cast which could not just fill every single theatre in the country but could also transform every harsh critic into an avid fan. I always thought it was The Goodfellas meets Wall Street, because it’s a story about ruthless criminals who would do anything to earn an extra buck and anything to spend it even faster.

Just like the 1990 gangster drama, the film is loosely (literally hanging by a thread) based on a real-life story. Instead of mobster Henry Hill, played by Ray Liotta, this time it is stockbroker Jordan Belfort, who, through various ‘fugazi’ ideas and schemes, made more money than Scrooge McDuck. Leo, who has played real-life con artists before, fell into the role like a hand inside a tailored velvet glove. It felt wrong seeing the real Belfort’s picture in the newspapers or on the internet because of the way Leo handled that character.

There are many similarities which I notice in The Goodfellas and the movie in question. While we obviously have the ambitious, strong-headed and problematic protagonist, we also have the crazy best friend. Jonah Hill is this film’s Joe Pesci, and both films have their Rat Packs consisting of morally bankrupt human beings. Margot Robbie and Lorraine Bracco also play similar characters, as both of them are beautiful and wilful girls who are doubtful of their partner but still attracted to the way he gets things done, using influence or money. Both aren’t pushovers either, as they take things into their own hands when Henry or Jordan act out of line. Although in that case, I would have to give Margot’s character more props, as she never folded once she knew her husband had gone off the rails.

Henry and Karen Hill (left) are quite like Jordan and Naomi (right).

Henry and Karen Hill (left) are quite like Jordan and Naomi (right).

Amazing soundtracks, fourth-wall breaking, and moments of pure chaos are other generalised similarities, but there is one important thing that is different. Henry in Goodfellas is always aware of his passion and the fact that being a gangster is against the law. For god’s sake, one of the opening lines of the movie is, “As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster.” He didn’t care that he would be on the other side of the law, and he started skirting it as soon as he had the ability to talk or run his way out of a situation.

Story continues below this ad

But Jordan isn’t like that. Take your mind to one of the first scenes of the film, where Jordan is having a meal with Mark Hanna, played by Matthew McConaughey. The latter tells him that the goal of a stockbroker is to move the money from the client’s pocket to his own, to which Jordan says, “But if we can make the clients money, it’s advantageous to everyone. Am I correct?” The answer from the other side is a straight “No”, and from there starts Jordan’s transformation into a man who is hell-bent on making money, without wondering about the consequences.

During that pursuit, Jordan sheds his old skin. His identity, morals, even his wife. For a bigger house, a fancier car, and a model named Naomi Lapaglia, because in his words, “There is no nobility in poverty. I have been a rich man, and I have been a poor man, and I choose rich every time. Because at least as a rich man, when I have to face my problems, I show up in the back of a limo, wearing a $2000 dollar suit and a $40k gold watch.” These words, the way Martin has shot this scene, with the camera following Jordan around a pool of associates and then putting him up on that stage (pedestal), change the dynamics between the audience and the character. It changes Jordan’s image in our brain.

You cheer for the perverse man, who has left his wife and jumped into a lifestyle of debauchery, filled with drugs, booze, stolen money, and the broken hearts of every person he duped. We hate the authorities for catching onto him, and we applaud him for getting away every time he does. The same thing happens when Ray plays Henry. The audience celebrates when he burns down the restaurant with Tommy or when he robs the Lufthansa airlines. They both ascend in our hearts, despite the shaky and bankrupt ladder they used to get there, and they both fall out of grace in the same manner. The last straw breaks when they hurt the woman of the story, the one humanising aspect that this deranged and greedy character flaunted around.

ALSO READ: James Gunn gets his Superman right, he’s awesome and predictable all at the same time

Story continues below this ad

You have to realise that Martin, the master storyteller, was still somewhat limited by what had happened in real life. He had to work his way around it and make sure that the characters don’t get rewarded for all that they did wrong in the film, something many Bollywood films could learn a little something from. They fly high, and they fly fast, but Icarus has to fall down, no matter what.

The genius is in how the director tells this intense story and how at no point he lets the narrative get too overwhelming or serious for the viewer to get through. The comedic timing of the film and its characters is so on point. Jon Bernthal punching Jonah Hill into the next Sunday is one of my favourite scenes from the film, also the way Joanna Lumley handles herself around Jordan – so sensuous and yet so proper. The gang of baboons is filled with actors like P. J. Byrne, Kenneth Choi, Brian Sacca, and Henry Zebrowski. All of them deliver a masterful performance, and maybe I am just a boxing fan, but Choi going full ‘ultimate fighter’ on Jordan’s househelp is hilarious.

Jordan Belfort’s group of delinquents. (Photo: IMDb)

Jordan Belfort’s group of delinquents. (Photo: IMDb)

From someone who is so gifted when it comes to making a gritty, dark and crime-ridden film, this film almost feels like Marty is saying, “I don’t make these, because it’s too easy for me.” A special shoutout needs to go to the DOP of the film, Rodrigo Prieto, and the editor, Thelma Schoonmaker. Their ideas and the treatment of those ideas are so in sync that a sudden slow-motion shot somehow doesn’t mess with the pace of the scene at all. The framing is masterful, and it complements whatever is going on in the whole act, not just a particular scene.

It’s playful, boastful, brutally brash and unapologetically itself. The Wolf of Wall Street might not be the greatest thing Martin Scorsese has ever made, but it is the wildest, most college-dorm, fever-dream flick that has ever come out of that man’s brain.