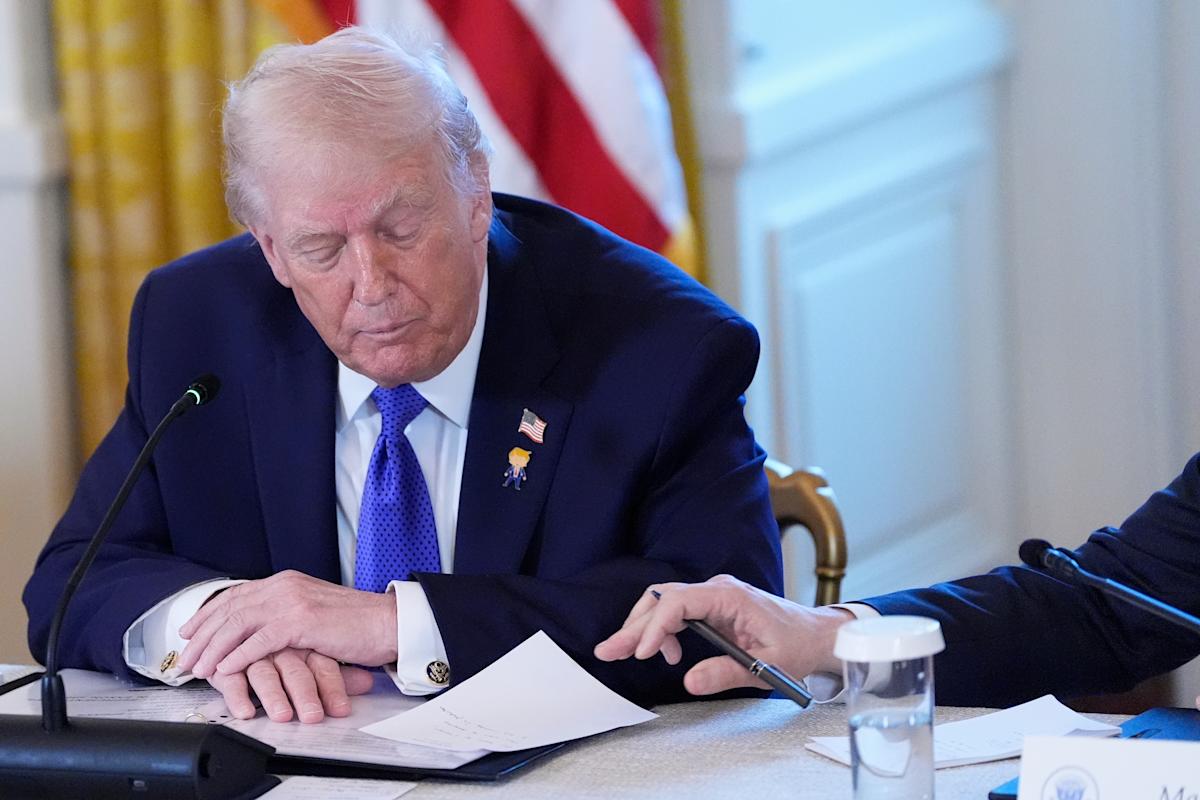

(Bloomberg) — President Donald Trump’s demand that credit-card lenders cap interest rates at 10% for a year takes aim at one of the banking industry’s crown jewels — a business line they guard doggedly.

After a week of jarring markets with announcements aimed at making homes more affordable, the president swiveled to another consumer burden: the cost of carrying a credit card balance from one month to the next. This time, his social-media missive pushed a slew of card issuers led by JPMorgan Chase & Co. (JPM), Capital One Financial Corp. (COF) and Citigroup Inc. (C) into the crosshairs.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Card interest rates — hovering above 20% in recent years — have become a target of lawmakers on both sides of the aisle, with bills popping up and meeting stiff resistance from the industry. Banking trade groups have conjured foreboding predictions of what would happen if rates were slashed, endangering profitability: Americans on the brink could lose access to credit and be left with payday lenders and pawn shops.

But in response to Trump’s call for rates to drop by Jan. 20, industry groups including the Bank Policy Institute and Consumer Bankers Association struck a more measured tone.

“We share the president’s goal of helping Americans access more affordable credit,” the groups said in a joint statement late Friday. “At the same time, evidence shows that a 10% interest rate cap would reduce credit availability and be devastating for millions of American families and small business owners who rely on and value their credit cards, the very consumers this proposal intends to help.”

For cash-strapped consumers who rely on cards for extra expenses, the cost of carrying a balance can be painful. The average interest rate remained around 21% at the end of last year, according to the Federal Reserve. At that level, paying down $10,000 over three years generates more than $3,500 of interest.

In contrast, the rate on a typical 30-year fixed mortgage — another familiar consumer product — is just above 6%, according to Freddie Mac data.

Banks have long argued unsecured card debt needs a high rate because of the inability to cushion losses when borrowers default: There’s no house or car to repossess. Indeed, after the financial crisis, charge-off rates on credit cards soared north of 10%, while those on residential real estate loans stayed below 3%.