The results describe participants’ understanding of uncertainty throughout the serious game experience, revealing changes from initial understanding to post-game perspectives. We start by examining how participants’ perceptions of uncertainty shifted between before and after the game, noting their evolving conceptualization of different uncertainty types. We then describe how their responses to uncertain conditions developed during gameplay, as teams adapted their strategies across the five rounds. Finally, we analyse the cognitive and normative learning patterns that emerged, examining how participants’ understanding and decision-making approaches were influenced by the game experience.

Participants perceptions of uncertainty

Before gameplay, participants demonstrated a relatively compartmentalized view of uncertainty, primarily anchored in climate scenarios and their direct physical implications. The pre-game view was characterized by a focus on direct external drivers like climate variability, flooding, and drought (16 participants), with participants typically viewing uncertainty as something to be anticipated and managed (14 participants) through conventional top-down planning approaches (12 participants) that showed limited consideration of systemic relationships. The post-game discussion revealed how this climate-centric anticipation had shaped initial gameplay strategies. When asked what new insights participants gained about uncertainty, one acknowledged: “[we] didn’t think about the political or the food crisis, we were really anticipating droughts”. The discussion moderator’s observation that multiple participants shared similar expectations “ I remember a group in that corner also saying something like, oh, the next thing must be a drought” highlighted the focus on biophysical climate impacts. This emphasis on direct climate impacts left participants surprised by the social and political disruptions that would emerge during gameplay.

After playing the game, the survey data indicated a shift towards acknowledging complexity, including systemic drivers and institutional factors. Post-game, strategic (35%) and substantive (33%) uncertainty became approximately equivalent in prominence, representing a shift from the pre-game dominance of substantive uncertainty (44%) (see Table 1). Additionally, institutional uncertainty grew from 23% to 32% of mentions, reflecting implementation challenges and governance dynamics that became apparent during the game. Analysing the quotes from the open answers, epistemic uncertainty (knowable unknowns) consistently represented a significant part of the described uncertainty, increasing slightly from 33% to 34% of all uncertainty references. Ontological uncertainty (inherent unpredictability) remained the largest category growing from 44% to 48%, while ambiguity (unclear problem definitions) decreased proportionally from 23% to 18%. This pattern suggests participants increasingly recognized limits to predictability while becoming more conscious about problem boundaries. As one participant reflected: “We must adjust and prepare for the uncertainty that comes from social attitudes and the ruling government”. With another participants mentioning: “using measures that are adaptive can more easily be made fit with unexpected scenarios”.

Analysis of coded uncertainty mentions revealed significant increases in both ontological (35 to 75 mentions, χ² = 14.55 df = 1, P < 0.001, φ = 0.36) and epistemic uncertainty recognition (26 to 53 mentions, χ²=9.23 df = 1, P = 0.002, φ = 0.34), suggesting participants identified more uncertainty overall rather than simply recategorizing existing concerns. The object of uncertainty also shifted: institutional uncertainty mentions increased most (18 to 50 mentions), followed by strategic uncertainty (26 to 55 mentions). Substantive uncertainty mentions increased moderately (35 to 51), though this did not reach significance (See SI6.1; Table SI6.1).

Participants developed awareness of system interconnections throughout the game. One participant during the post-game discussion noted that specific land-use types such as intensive agriculture are particularly vulnerable because “there are too many factors that make it vulnerable like both socio-economic as well as environmental”. This is indicative of how increased awareness of interconnectedness also informs participants of cascading effects of climate change impacts. In the post-game discussion, one of the participants explicitly stated players gained “a more complete idea… of different types of uncertainties that can come”. Where a different participant described how their group initially focused only on droughts and floods but was “most surprised” by the food crisis, recognizing diverse uncertainties beyond direct climate impacts. The serious game effectively highlighted multiple dimensions of uncertainty that participants had not previously considered in adaptation planning. One participant highlighted the impact of unpredictable events: “The event cards really influenced uncertainty. It changed the way we selected measures because we were trying to anticipate for scenarios from the event cards but of course we had no idea what it could be”. Not all participants found the game equally effective. Approximately 11 participants (20%) reported the game did not substantially enhance their understanding of uncertainty (ratings ≤3/5). Analysis of these responses suggests heterogeneous reasons: some participants (n = 4) indicated they already possessed sophisticated understanding of uncertainty from prior coursework (“It showed the complexity which I was already aware of”), others (n = 3) found the game’s simplified mechanics did not capture real-world complexity (“This game is an incomplete situation… so it didn’t change my understanding much on a fundamental level”), and several (n = 4) expressed that insights were not revelatory (“It broadens my vision but doesn’t deepen my understanding”).

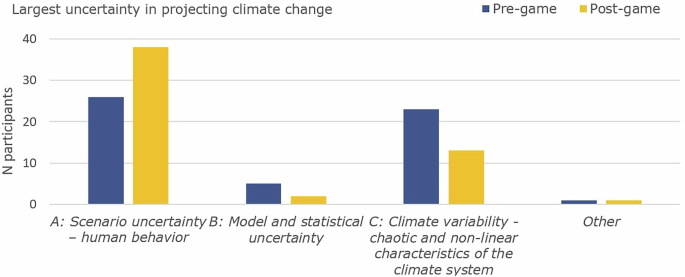

The political dimension emerged particularly strongly, with Speaker 1 finding political shifts impactful: “That experience of the frustration [of political change] is very visceral” and “that’s actually happening now in the real world”. Another participant contextualized this within their broader experience: “when you’re involved with climate in general and adaptation measures, everywhere you look, you always get faced with uncertainty about this sort of build this”. The political event (populist government) prompted a strong reaction, even though political events could often be considered reversible in contrast to some environmental changes due to climate change. The reactions to these events indicate that the game expanded participants’ understanding of uncertainty beyond environmental factors to include the social and political dimensions that can influence adaptation outcomes. Which was also evident in a slight shift towards naming human uncertainty as the largest uncertainty in project climate change (Fig. 3). The impact of this shift was evident when one participant expressed pessimism about the relationship between planning and politics in the post-game discussion: “I feel even more insecure about adaptation planning now because once the populist show up, they’re [adaptation measures] being tossed out of the window… [even]If you plan in the perfect scenario, they don’t come out and then break it apart again as well”. This represented a stark contrast from the pre-game survey quote that “if there is a will in the political world, it will happen”.

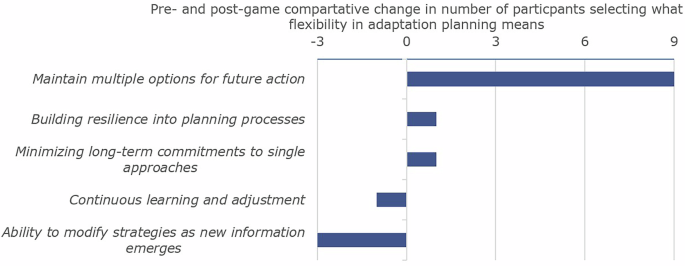

Nearly two-thirds of participants identified either alignment of organizations and governments (23) or practical implementation (15) as the most critical factor for effective adaptation pre-game. Most respondents post-game preferred adaptation measures that are adaptable and flexible (42) rather than tailored to specific scenarios (4), further supported by a shift in preference of 9 participants for maintaining multiple options post-game (see Fig. 4). This preference was supported by Speaker 4’s description of investing in “soil quality and water quality” as “generally good” regardless of future scenarios, showing incentive to find measures that provide long term flexibility. Arguing that these measures are unlikely to be challenged or otherwise impacted by the various events, and therefore keep other options that could respond to events open.

Responding to Uncertainty

In-game survey results show a development in decision-making strategy throughout the game. Initially, most teams prioritized long-term vision, with 82% (9/11 groups) reporting no strategic impact in round 2, reflecting confidence in their ability to anticipate future conditions. However, environmental events and time constraints increasingly disrupted these strategies. By rounds 3-4, over half the teams (6/11 in round 3, 8/11 in round 4) reported strategy impacts demonstrating growing recognition of uncertainty (Table SI6. 4). Group certainty ratings showed a bell-shaped pattern across rounds. Teams reported moderate certainty in round 2 (M = 6.05, SD = 1.88), which increased in round 3 (M = 6.73, SD = 1.35), before comparatively declining in round 4 (M = 6.05, SD = 1.42) and round 5 (M = 6.10, SD = 1.73). While effect sizes comparing round 3 to other rounds were moderate (round 2–3: d = 0.42, round 3-4: d = 0.49, round 3-5: d = 0.44), differences did not reach conventional significance thresholds (all P > .14), likely due to limited statistical power with 11 groups (see Table. SI6. 3). Nevertheless, the pattern suggests participants initially gained confidence in their adaptive responses before implementation realities eroded certainty in later rounds. Looking at individual groups: 3 of 11 groups maintained high certainty, 4 groups showed declining confidence as the game progressed. Teams that focused on resilience and adaptability tended to remain certain, whereas those oriented toward specific outcomes were more vulnerable to change. These dynamics suggest that experienced preparedness for uncertainty could rely less on anticipating exact futures and more on keeping options open to preserve flexibility.

Gameplay observations revealed diverse responses to uncertainty. When the populist government event occurred in round 4, groups demonstrated contrasting reactions. Group 8 noted they “were on the right road and need to align with the events card” choosing to reverse previous nature-focused measures to align with the new political priorities. Their certainty actually increased to 8.5/10 in round 4, suggesting confidence in their adaptive capacity. In contrast, group 7 reported “We sure got more insecure but still did things” with their certainty dropping to 4/10, as they struggled to reconcile their long-term vision with political disruption. Strategic approaches also diverged in response to time constraints. Group 4 maintained adaptive capacity, noting they could still “Get as much done as possible and aim for 80% match to final vision [and prepare for a] green transition” demonstrating intentional maintenance of optionality. The flood event in round 2 elicited varied interpretations. Group 5 reported “We anticipated the right thing and chose caution, got lucky that we focused on water safety” framing their preparedness as strategic foresight. Meanwhile, Group 1 noted they were simply pursuing “long term solution” focused on “Ground water level, [and to] realize [the] vision”, citing they were unaffected because “We did not do something that was affected by the flooding”. This illustrates how external events generated different learning depending on groups’ strategic positioning.

The post-game discussion revealed development in strategic thinking across the gameplay experience. When asked what insights they gained, one participant reflected on the danger of overreacting to individual events: “when we see one event, we might tend to change something, but actually in our experience we just left something the way it is and then the next event come about and actually that earned us some points… the turning point of the changes in the situation doesn’t necessarily mean that’s the new feature to stay, so there could still be more changes to come where our measures might even still work in the future”, suggesting an appreciation of temporal complexity and potential chaotic nature of adaptation planning. Another participant described how their strategy emphasized maintaining broad options: “we keep it flexible… …to increase resilience [by] investing [in] things that doesn’t matter what happens [are] just generally good”. When asked about their approach if playing again, one participant who had initially adopted a “go big or go home” strategy acknowledged they would shift toward “low regrets” measures. Another emphasized they would implement “more flexible options and there’s also just in general more uncertainty that I would think about”. When the moderator probed whether feelings of gambling increased or decreased during gameplay, one participant captured the nuanced reality: “I think it decreased, but even at the very end we were having a discussion… I think it decreases and it increases based on if you’re lucky”. This indicates a recognition that uncertainty cannot simply be resolved through better planning, but must be actively navigated. Taking a more nihilistic perspective a group used chance in their decision-making, with one describing moments “where we’re like, OK, choose a number, and then we’ll decide on if you guess the number correct. If you go for one or [another option]”, illustrating how groups sometimes resorted to randomization when faced with irreducible uncertainty.

Reflecting on the game in the individual surveys, participants’ perception of uncertainty changed throughout the serious game, revealing insights about implementation challenges that extend beyond theoretical planning. As one participant reflected, “The more flexibility you have, the easier it is to adapt to changes in any situation, either geophysical or political”. This highlights a key finding: adaptation involves not only planning under uncertainty but also navigating the uncertainties that emerge during implementation. Participants began to articulate a more sophisticated understanding of temporal dynamics in adaptation planning. When discussing lessons learned, one participant explained: “the lesson that I find most important is basically to think in intervals instead of thinking from now to 50 years… if you were to think now what would happen in 50 years, what do I do to get there, you don’t think about the things that happen within those 10 year [steps] and that shorter term thinking within the long term, that’s something that I found very interesting”. When asked by the moderator on whether this would change their approach “if you were now the civil servant planning for that 15 years, would you change the decisions compared to before the game?” the response was: “I would [choose] more flexible options and there’s also just in general more uncertainty that I would think about”. Ultimately, implementation realities eroded initial strategy adherence, with only a minority of teams maintaining their original approaches throughout the game.

When asked what they might use in future work or studies, one participant emphasized the importance of looking beyond immediate research boundaries: “we don’t only look at inwards to what we’re doing, what we’re researching… it’s very important to really look outside to see how things are changing like weather wise or political wise… that external look is very important. That will give us maybe earlier signal on what we should focus on in the future”. Another participant contextualized this within the broader challenge: “there are things that you just cannot change by studying”. This supports an evolution from the pre-game emphasis on anticipating specific climate scenarios, toward recognizing the need to monitor and respond to diverse external signals.

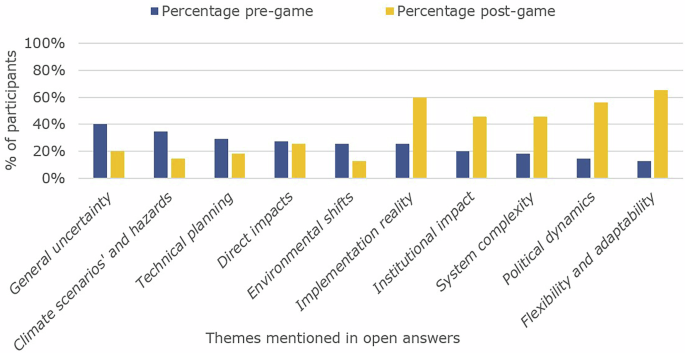

Despite increasing time pressure and the difficulty of mid-game adaptations, participants reported a high level of appreciation for the serious game experience. On average, they rated the game as enjoyable (4.6/5, N = 54), valuable for enhancing their understanding of adaptation pathways (3.7/5, N = 54) and valuable for learning about different dimensions of uncertainty (3.8/5, N = 54). Changes in uncertainty perception based on the uncertainty framework showed several themes and subthemes. Participants referred to ontological uncertainty related to institutional object, uncertainty related to implementation (strategic), environmental uncertainty (substantive), and interpretation of adaptability and flexibility in response to these uncertainties (strategic) (see Fig. 5). Chi-square tests confirmed the significance of these thematic shifts. Recognition of political dynamics increased from 15% to 56% of participants (χ² = 13.56 df = 1, P < 0.001, φ = 0.5, medium to large effect), while mentions of flexibility and adaptation grew from 13% to 65% (χ² = 19.56 df = 1, P < .001, φ = 0.6, large effect). Institutional impact recognition increased from 20% to 45% (φ = 0.31), and system complexity awareness grew from 18% to 45% (φ = 0.34). Implementation reality mentions increased from 25% to 60% (φ = 0.37). Conversely, exclusive focus on climate scenarios decreased from 35% to 15% (φ = 0.29), suggesting participants broadened rather than merely shifted their understanding of uncertainty sources (Table. SI6. 2). Institutional uncertainty proved particularly disruptive (supported by the shift in recognition of political dynamics), as one participant reflected, “My view on uncertainty is largely the same, although now with greater weight on the political aspects of uncertainty”. This shift was also evident in survey data, where scenario uncertainty and human behaviour gained more attention than climate variability (see Fig. 3). Teams that acknowledged time constraints in later rounds were more likely to report strategic impacts, while those that built flexibility in early rounds were sometimes less affected. One participant remarked, “I realised that you become more unsure of your strategy when your plan changes the first time, you get more scared of the uncertainty”.

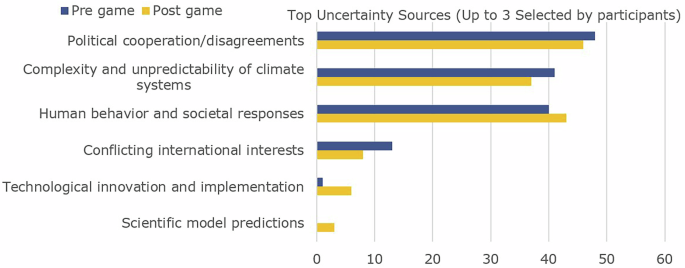

Survey data demonstrated that participants most frequently identified political cooperation (n = 48), human behaviour (n = 40), and climate system complexity (n = 41) as primary sources of uncertainty (Fig. 6). Despite the emergence of new thematic categories (Fig. 5), participants’ fundamental perceptions of uncertainty remained largely consistent between the pre- and post-game survey, in spite of shifting perspectives on political dynamics, implementation challenges, institutional impact, and system complexity. This consistency suggests that the serious game primarily challenged and refined existing uncertainty perceptions rather than fundamentally transforming participants’ conceptual frameworks or imposing deterministic perspectives through the selected event or survey design. The marginal reduction in emphasis on climate system complexity and unpredictability may, however, be attributable to the thematic shifts induced by specific in-game events and scenarios.

Cognitive learning

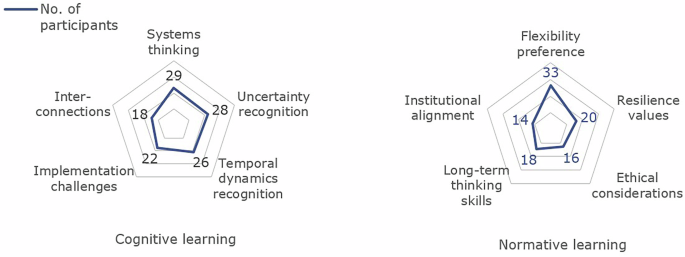

The serious game stimulated cognitive learning effects (acquisition of new knowledge or structuring of existing knowledge31) across multiple dimensions, resulting in participants shifting from linear to systems thinking. This evolution is supported by an increase from 21/55 to 32/54 participants describing multiple forms of uncertainty by the end of the game, mentioning different forms of uncertainty that could impact adaptation efforts instead of focussing on a singular aspect such as physical or social change (see Fig. 7). Additionally, participants developed a more elaborate understanding of temporal dynamics, recognizing that adaptation is iterative in practice rather than exclusively endpoint-focused. The round-based structure to progress the game, comprising five sequential rounds, each representing a ten-year period with limited resources, fostered understanding of how decisions unfold over time, with participants recognizing limitations of planning exclusively for distant endpoints rather than adaptive pathways. This was reflected in an increase from 3/55 to 32/54 participants explicitly naming flexibility as a strategy (see Fig. 7).

Cognitive learning is represented by five themes: Systems Thinking (understanding interdependencies and cascading effects), Uncertainty Recognition (acknowledging diverse forms of uncertainty beyond climate), Temporal Dynamics (recognizing adaptation as an iterative, time-sensitive process), Implementation Challenges (understanding the gap between planning and practice), and Interconnections (seeing how systems and stakeholders mutually influence outcomes). Normative learning is represented by five themes: Flexibility Preference (valuing adaptable over rigid approaches), Resilience Values (adopting resilience as a guiding principle), Ethical Considerations (emphasizing fairness and responsibility in adaptation decisions), Long-term Thinking (prioritizing generational over short-term perspectives), and Institutional Alignment (valuing coordination across organizations and governance levels).

Participants gained practical insights on implementation challenges, with uneasiness about the effectiveness of planning and implementation frequently mentioned. The gap between planning and implementation was observed across 22/54 participants (see Fig. 7). As one participant reflected: “For example: we thought we were implementing effective measures, however in the end they were not as effective”. Another noted: “The fact that taking measures that in the following period were not desirable anymore gives me the feeling that often it is unfortunately not possible to plan long term because of uncertainty”. Some participants demonstrated improved capacity to anticipate uncertain events, moving from reactive responses in early rounds to more strategic anticipation of potential disruptions (25/54 participants, Fig. 7). This was supported by the choice to maintain multiple options and avoiding early lock-in (42/54 participants), a perspective that aligns closely with the pathways approach and represents a cognitive advancement in adaptation planning capabilities. Flexibility was also acknowledged during the post-game discussion through concrete examples. When asked about changing their perspective on uncertainty, one participant noted: “we can’t 100% [be] prepared, but it’s good to be aware of things that can happen”. Another described how “the game provided concrete examples of what can happen and what kind of surprises that can [occur]”. The need for flexibility was primarily driven by the recognition of interconnections and systems thinking when confronted by adaptation planning (Fig. 7). Collectively, these findings suggest that participants developed a more nuanced understanding of adaptive planning, one that embraces uncertainty as unavoidable while building capacity for strategic flexibility and anticipatory decision-making.

Normative learning

The serious game stimulated normative learning effects (learning related to viewpoints, paradigms and value shifts31), with a strong preference for flexible, low-regret strategies emerging post-game. As one participant stated: “Adaptation measures should be flexible, because there can be a lot of change in the future you can’t prepare for”. This represents an evolution from isolated goal-oriented thinking to valuing resilience and adaptability (20/54 participants, Fig. 7). This could also be observed in participants becoming comfortable acting despite uncertainty, moving from trying to predict futures to finding factors contributing to resilience (14/54 participants). This shift is illustrated by pre-game statements such as “This uncertainty mostly refers to uncertainty that is for now impossible to reduce, so you can’t ever be absolutely certain” compared to post-game reflections like “Stay adaptive to tackle uncertainty for what happens after you planned for it”. Participant perspectives on flexibility within adaptation planning also shifted, as illustrated by one participant whose view evolved from pre-game “Not being absolutely sure about the factors involving climate adaption planning” to post-game “By being flexible it allows to adapt to changing conditions in climate but also in for example politics”. Additionally, cognitive learning facilitated normative learning in a subset of participants: increased understanding of system complexity led to greater humility about control limits of the system (10/54 participants) and recognition of diverse uncertainty types prompted value shifts toward flexible approaches (33/54 participants). These interconnected learning processes ultimately influenced participants’ values about adaptation decision-making, with observable effects moving participants from certainty-seeking to uncertainty-embracing approaches that prioritize adaptive capacity over predictive control.

Debriefing responses revealed distinct strategies that had emerged. Some participants adopted precautionary approaches: “We tried to anticipate for scenarios from the event cards but of course we had no idea what it could be” demonstrating attempts to prepare for unknown unknowns. Others embraced opportunistic adaptation through iterative adjustment over long-term commitment. A third pattern emphasized robust baseline improvements, with one participant describing investing in “soil quality and water quality” as “generally good” regardless of future scenarios, indactive of low-regret strategies that maintain flexibility across multiple futures. These reflections, in conjunction with the survey results, provide triangulating evidence for systematic shifts observed in coded survey responses. Participants demonstrated increased willingness to make decisions under uncertainty by building flexibility into strategies, as experienced certainty about outcomes decreased. A subset of participants began incorporating ethical considerations alongside technical solutions (16/54 participants), showing deeper normative learning about value trade-offs inherent in adaptation planning (see Fig. 7). Furthermore, participants experienced increased skill in balancing immediate needs with long-term sustainability considerations (18/54 participants), as reflected in this observation: “You don’t know what [events are] going to happen so using measures that are adaptable is always good. Also considering the long term, we skipped out on changing to [(intensive agriculture] in round 4 as we thought that this wouldn’t be sustainable in the long term, which turned out to be a good decision”. Additionally, there was recognition of the role of institutional alignment and community response (14/54 participants) in successful adaptation strategies, representing a broader normative shift in how participants conceptualized effective climate governance (Fig. 7). However, these shifts should be understood as representing only a subset of all participants, highlighting that though learning is evident; the themes reflect specific clusters of learning within the group and context of this study.