On February 24, 2022, Putin shocked the world by invading Ukraine, shaking European stability to its core. Claiming to be protecting Russian-speaking populations and resisting Ukraine’s drift towards NATO, Moscow launched the largest European war since World War II. Although it stunned the world, this was far from a sudden move. This invasion echoed a familiar pattern seen in Georgia and Crimea years earlier, a pattern the West had been too scared to recognize until it was too late. Understanding these earlier conflicts is essential to recognizing the recurring nature of Russia’s aggression and the dangers of Western complacency.

At the 2008 NATO Bucharest Summit, the alliance considered admitting Georgia and Ukraine, but faced disagreement, with some concerned about antagonizing Russia. Although NATO ultimately refrained from initiating the formal accession process, it decided on a compromise. It issued a statement declaring that, in the future, “these countries will become members of NATO.” From Moscow’s point of view, this wasn’t much of a compromise. Putin himself declared that the admission of these two countries into NATO would represent a “direct threat” to Russia. With NATO increasing its outreach to its neighbours, Russia became hypervigilant towards pro-Western movements in both countries.

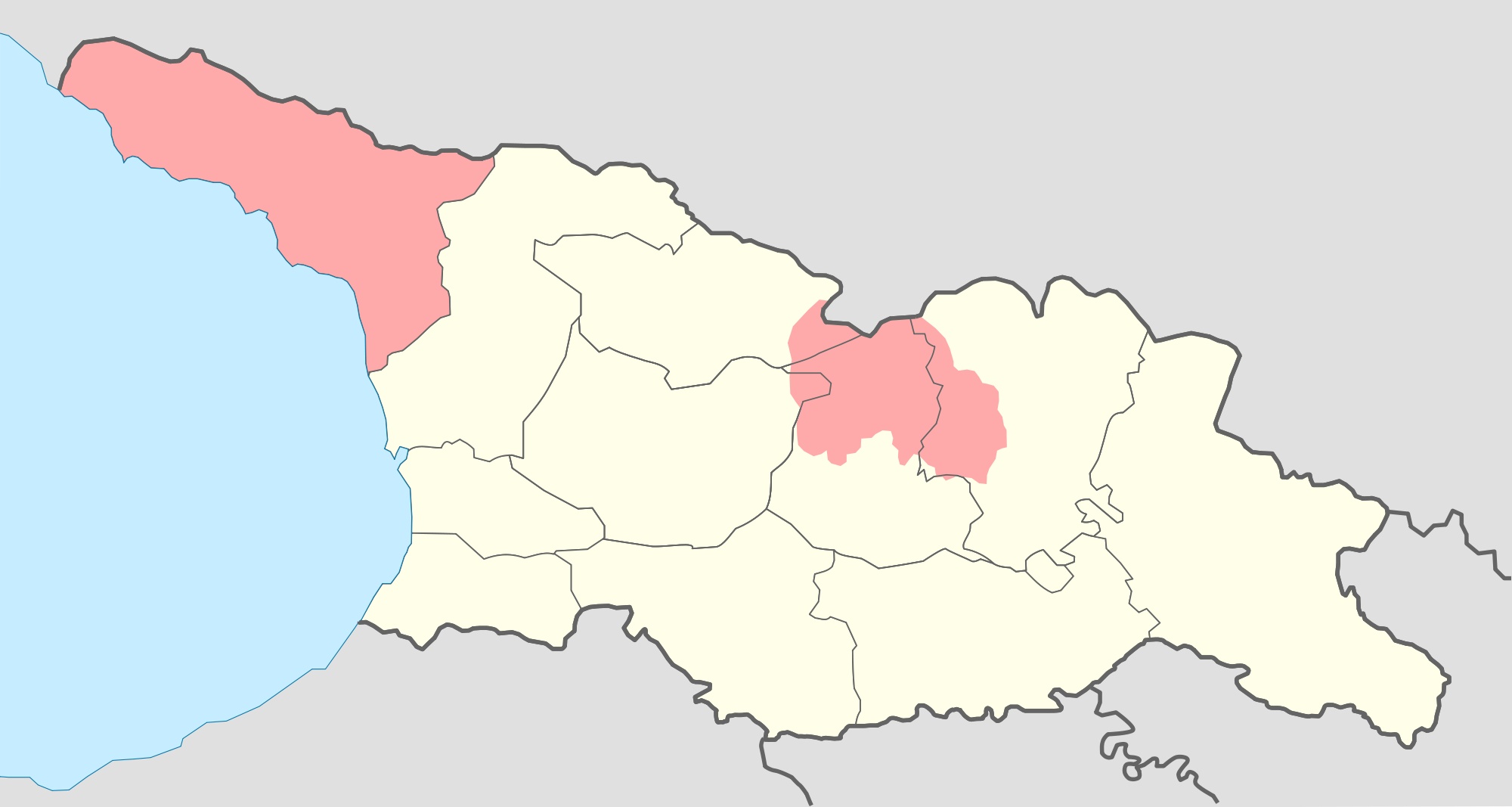

Map of Georgia highlighting the Breakaway regions of Abkhazia (highlighted region to the left) and South Ossetia (highlighted region to the right). “Map of Georgia with Abkhazia and South Ossetia Highlighted” by Alaxis is licensed under the public domain.

Map of Georgia highlighting the Breakaway regions of Abkhazia (highlighted region to the left) and South Ossetia (highlighted region to the right). “Map of Georgia with Abkhazia and South Ossetia Highlighted” by Alaxis is licensed under the public domain.

In August of 2008, conflict erupted between Georgia and the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, regions that both touch Russia’s border and have strong pro-Russian ties. Under the guise of protecting the Russian speakers in those regions, Russia swiftly intervened. In a five-day-long conflict, Russia defeated the Georgian troops, displaced almost 200,000 people, and declared Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states.

This move was loudly condemned by the West, namely the US, the EU, and NATO. However, in practice, Russia faced little to no consequences. Although the EU temporarily ceased partnership talks with Russia and Russia’s membership in the G8 was frozen, no coordinated sanctions were enacted, and NATO and the US, save for sending humanitarian aid to Georgia, did not intervene. In fact, within just a few months, all EU-Russia relations were normalized, and the conflict was viewed as a regional issue rather than a sign of broader aggression. With little more than a slap on the wrist, Russia likely inferred that any of the benefits from invading Ukraine would exceed the minimal costs.

The conflict in Crimea began in late 2013, when then-President Viktor Yanukovych scrapped an EU-Ukraine trade agreement that would bring Ukraine closer to EU membership in favour of trade with Russia. This outraged many Ukrainians, who took to the streets in protest during the Euromaidan Revolution. These nationwide protests quickly turned violent, leading to over 100 deaths and Yanukovych fleeing to Russia.

In late February, unidentified pro-Russian militants, only identified by Putin as Russian soldiers at the end of the conflict, seized several public buildings in Crimea, including the airport, military bases, and Crimea’s governmental headquarters. In Russia, Putin publicly condemned the pro-West shift in Ukraine, claiming that the new Ukrainian government was made up of “nationalists, neo-Nazies, Russophobes and anti-Semites”. This conflict culminated in a referendum overseen by pro-Russian troops that took place in Crimea to vote for or against their annexation. The referendum passed with an astounding 95.5 per cent in favour of annexation. Despite the loud protests of the West and accusations of rigging the referendum, Russia annexed Crimea.

The Euromaidan protests, which began in late 2013, sought to remove then-President Viktor Yanukovych from power. “Euromaidan” by jlori is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The Euromaidan protests, which began in late 2013, sought to remove then-President Viktor Yanukovych from power. “Euromaidan” by jlori is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

There are many parallels between these two conflicts. In both cases, Russia used humanitarian rhetoric of ensuring the safety of Russian speakers in Georgia’s breakaway regions and newly pro-West Ukraine to justify its attack. In both cases, Russia’s interventions were swift and decisive, five days in Georgia and just a few weeks in Crimea, and relied on surprise attacks and special forces troops to quickly gain control.

Most importantly, both countries were taking decisive steps towards alignment with the West when Russia struck. Georgia had Mikheil Saakashvili and his administration, who made EU and NATO membership central to his foreign policy goals. Russia, through the invasion, propaganda, and other subtle manipulations, undermined his administration, and he was replaced with a more Russian-friendly leader. This same pattern can be observed today, with Putin continually attempting to undermine Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s administration in similar ways. After their respective invasions, both countries were left with frozen conflicts, making NATO membership impossible for the foreseeable future.

Russia faced greater consequences after annexing Crimea, receiving economic sanctions, trade limitations, and diplomatic isolation, such as suspension from the G8, now the G7. However, despite harming Russia, the consequences were at best moderate and failed to curb its aggression. Russia had not yet faced strong enough costs to outweigh the benefits of invasion, leading to its actions from 2022 to now.

Another similarity between the two invasions is the economic state of both Ukraine and Georgia at the time of their respective conflicts. Right before their invasions, these countries’ economies were on the rise, with Georgia’s economic growth averaging just over 10 per cent per year between 2005 and 2007, and Ukraine’s GDP growth rate around 3 per cent. This growing economic independence led both countries to seek closer economic ties with the West, a development Moscow disapproved of. As these countries reduced their economic dependence on Russia, the regional hegemon’s sphere of influence inherently decreased. To prevent this economic integration with the West, Russia resorted to hostility to dampen their economies and keep them both under Russia’s firm thumb. Although Russia’s actions damaged both countries’ economies, they also ironically led to both countries strengthening their efforts to trade with the West. This outcome reveals that while Russia employed similar strategies in Georgia and Ukraine, it ultimately did not learn from its previous mistakes.

Perhaps the most crucial similarity between these two conflicts is the West’s reaction. Although the West imposed certain consequences, they did little to deter Russia’s aggression. Western leaders may have publicly denounced Russia’s actions and issued statements reaffirming Georgia and Ukraine’s sovereignty, yet their fear of confrontation with Russia prevented concrete action. From the five bloody days in Georgia in 2008 to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine today, Russia has consistently demonstrated its persistent aggression and willingness to follow through.

In 2009, following payment disputes between Russia and Ukraine, the Russian-controlled company Gazprom cut off gas supplies to Ukraine, leaving southeastern Europe without gas for 13 days and resulting in significant economic losses for Ukraine. In 2017, a massive cyberattack known as “NotPetya” targeted Ukrainian government agencies and companies but ultimately spread worldwide, causing extensive collateral damage. Although Russia has denied responsibility for the event, multiple intelligence agencies, including the British National Cyber Security Centre and the American Central Intelligence Agency, have concluded that Russia was behind the attack.

Putin has gone as far as to discredit the existence of Ukraine on multiple occasions. In an article published in July 2021, he called the modern Ukrainian state “project anti-Russia,” and menacingly wrote, “We shall never allow our historical territories and the people living there who are close to us to be used against Russia. And I want to tell those who try it that by this they are going to destroy their own country.” Amidst these glaring warnings, the West continued to hesitate and offer weak, delayed, and largely symbolic reactions, allowing Russia to continue its pattern of aggression.

Russia’s actions in Georgia, Crimea, and now the whole of Ukraine reveal a clear pattern: swift attacks justified as defence, and aggression were met with a hesitant Western response. Ignoring these patterns allows history to repeat itself, often at a high cost. Recognizing these actions should not be done in hindsight—it must be done now to predict future conflicts and respond before it’s too late.

Edited by Avianna Zampardi

Featured image: “Vladimir Putin with Mikheil Saakashvili-4” by Presidential Press and Information Office is licensed under CC BY 4.0.