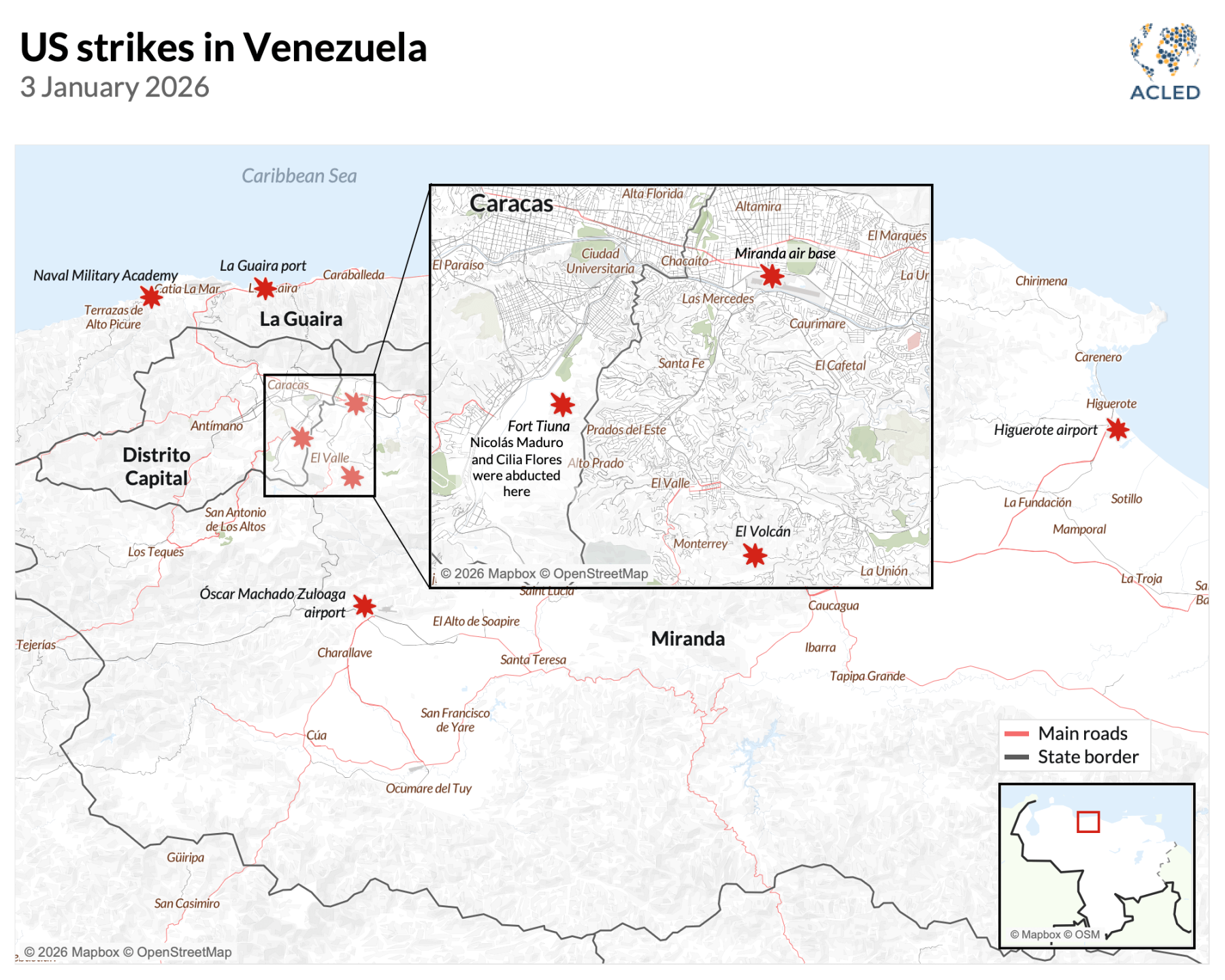

On 3 January, the United States carried out a military operation in Venezuela and captured President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores. During the operation, over 150 US aircraft targeted at least seven different military facilities in Caracas, La Guaira, and Miranda (see map below), neutralizing Venezuela’s defense systems. The precision of the strikes and the complete lack of military response have led some observers to speculate about a possible betrayal in Maduro’s inner circle.

While US forces did not suffer any losses, at least 74 Venezuelan and Cuban soldiers — most of whom were part of Maduro’s security detail and tried to repel the US special forces’ incursion — were killed. At least three civilians were also killed in the strikes, while Venezuelan government officials claim the civilian death toll could be in the dozens.

Vice President Delcy Rodríguez was sworn in as interim president on 5 January by the legislature presided over by her brother, Jorge Rodríguez. She has already received the backing of Defence Minister Vladimir Padrino and of several foreign allies, including Russia and China. At the same time, the Trump administration has apparently excluded the opposition’s main figure, María Corina Machado, from its plans to take control of the country’s oil business, although US Secretary of State Marco Rubio has outlined a three-phase plan that will lead to a transition, without outlining when and how this will take place.

ACLED Senior Analyst for Latin America and the Caribbean, Tiziano Breda, explains which elements within Venezuela and abroad might challenge Rodriguez’s ability to maintain stability.

Will Maduro’s capture spark unrest?

While a full-fledged regime change would have likely triggered an immediate violent backlash from the political, economic, and military elite that sustained Maduro’s government, the stability of Rodríguez’s tenure is far from granted.

The fact that the US intervention did not spark massive mobilizations rejecting the action is a testament to the widespread dissatisfaction with the Maduro administration, which Rodríguez has long been part of. ACLED records only a handful of protests demanding Maduro’s release, led mostly by government employees and ruling party affiliates, and just in Caracas.

To prevent Maduro’s arrest from emboldening opponents to take to the streets — as many Venezuelans living abroad have already done to celebrate Maduro’s removal — the government has imposed a state of emergency that restricts citizens’ right of assembly and directs authorities to search for and arrest anyone who expresses support for Maduro’s capture. Pro-government militias known as “colectivos” — controlled by Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello and key actors in the repression of dissent — have been spotted setting up checkpoints in Caracas. Preventive repression and uncertainty over the country’s political future have contributed to maintaining quiet in the streets. However, expectations for political change or, at the very least, a less repressive environment, remain widespread, and the recent release of over 40 political prisoners may further raise these expectations, nurturing a latent risk of unrest.

Will Rodríguez face a potential outbreak of violence?

A post-Maduro Venezuela faces multiple risks of violence, which could come from both within and without the Chavista power structure. As Hugo Chávez’s handpicked successor, Maduro had managed to conciliate different currents of Chavismo, from the most averse to US imperialism — particularly in the security apparatus led by Padrino and Cabello — to those more amenable to the free market and liberalism. Rodríguez must perform a balancing act: avoid overt confrontation with the US and comply with some Washington demands without appearing too acquiescent, which would not bode well with more radical Chavista factions. Losing the favor of even part of the security apparatus, whose leaders — Padrino and Cabello — have outspokenly rejected the US intervention, could trigger violent power struggles.

But colectivos and the military are not the only actors with a stake in preventing a shift toward a more US-lenient regime. Colombian armed groups such as the National Liberation Army (ELN) and some dissident factions of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) have thrived in a relatively permissive environment and with the political backing of Maduro’s government. They have established a presence in the country, particularly in key drug trafficking corridors along the border with Colombia, as well as near gold mining and oil extraction sites, where Trump is pressuring US oil corporations to step up their presence and investment (see map below).

The ELN and FARC’s General Central Staff, in particular, have pledged to defend the Bolivarian revolution in Venezuela and could put up an armed resistance against a government subdued by Washington. So far, this has been limited to issuing statements denouncing Maduro’s extraction and signs that it has moved its leadership to border states.

Finally, dozens of organized crime groups operate in Venezuela. The operations and size of most of these groups — which were once on good terms with Maduro’s government — have been reduced in recent years, as Venezuela’s economic collapse limited their criminal activity, and Maduro’s administration drove a shift toward a more hardline approach to crime. It’s unlikely that organized crime groups will seek to play an active role in the country’s political transition, but they add to the array of security challenges Rodríguez faces.

Can further US action be expected in Venezuela?

Washington has made clear that, if Rodríguez fails to meet its demands or if there are any official attempts to disrupt the transition, further US military actions will follow, even though Trump is confident that it will not be necessary. However, having lost the element of surprise, another US strike could be met with more resistance and thus be deadlier, including on the US side. Furthermore, Maduro’s removal has already raised suspicions and tensions within the Venezuelan government; targeting another high-ranking official would make internecine bloodshed more likely, particularly if it were to be someone who controls security forces and militias in the country, such as Cabello.

Meanwhile, Washington’s naval blockade is likely to continue hindering Venezuela’s ability to commercialize US-sanctioned oil, as the US has shown its resolve to chase oil tankers attempting to evade its blockade as far as the North Atlantic, regardless of what flag they fly. Undercutting oil revenues that helped to keep the Chavista elite united could increase pressure on Rodríguez to strike unfavorable deals with the US, hindering the government’s cohesion.

It is unclear whether the Trump administration will continue using the targeting of suspected drug smuggling vessels at sea as a pressure tactic on the Venezuelan government, now that it has escalated to land attacks, and Maduro — the head of drug trafficking operations in the eyes of US prosecutors — is in a US jail. Trump has boasted that the strikes on 34 vessels since September, which killed 110 people, have halted maritime drug trafficking toward the US and hinted at the possibility of turning to drug cartels on Mexico’s soil. However, the US will likely want to gauge the full national and international consequences of the intervention in Venezuela and ensure that the country does not fall into chaos first. Yet, paradoxically, success in prompting a smooth transition in Venezuela with limited political backlash or even widespread approval in the US may increase the risk that direct military actions will become a feature of US policy in the region.