By Kali Coleman

This article was originally published by Truthout

The mayor can’t rewrite state law, but he can take steps toward decriminalization and minimizing sex worker arrests.

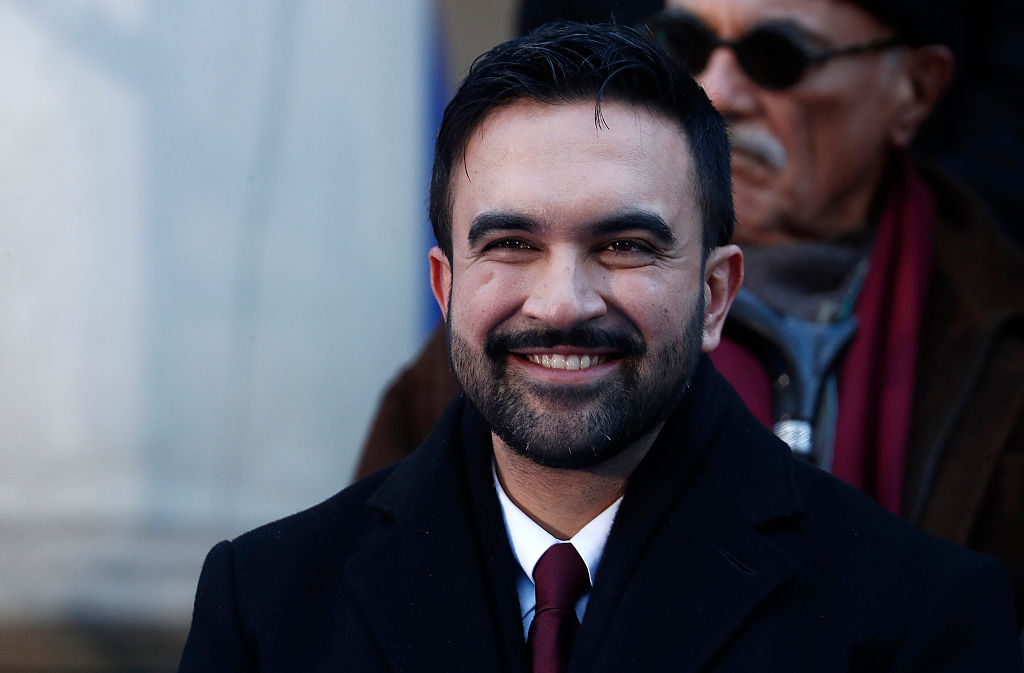

“I was elected as a democratic socialist and I will govern as a democratic socialist,” New York City’s new mayor Zohran Mamdani announced to vigorous applause at his inaugural speech on January 1, 2026. “I will not abandon my principles for fear of being deemed radical.”

The Mayor’s speech touched on the primary question at play in New York City, a familiar one for progressives nationwide: Will this elected leader be able to translate campaign rhetoric into material changes after entering the court of real-world politics?

When it was reported in December that Jessica Tisch would be retained as police commissioner, some speculated that Mamdani was making, as many New York City mayors have made before him, significant concessions to the political concrete wall of the NYPD. But maintaining a decarceral ethic is crucial to defending those most at risk in New York City, particularly amid Donald Trump’s draconian immigration policies. Mamdani has repeatedly stated that he is “ready for any consequence” in resistance to the president’s deportation regime. In the leadup to his inauguration and following an attempted ICE raid on Canal Street in December, Mamdani posted a brief “know your rights” video to YouTube, a brief primer addressing the basic tools of citizen resistance. Mamdani’s posting of the video also came on the heels of the detention and separation of a Chinese father and his son after a scheduled immigration hearing at 26 Federal Plaza, the site of a substantial number of recent deportations just around the corner from Manhattan’s City Hall. In the video, Mamdani walks through the minimum standard of legal paperwork required for ICE to gain entry into a private residence, listing what can be done in the case of an interaction with agents (filming is permitted; resisting arrest is not), and expresses unequivocal support for the city’s immigrant community. “I’ll protect the rights of every single New Yorker,” he says, “and that includes the more than 3 million immigrants who call this city their home.”

Mamdani’s vocal resistance to Trump’s immigration policy is admirable. What his messaging does not address, however, is another community whose criminalization is deeply entangled with immigration enforcement: sex workers. Migrants and sex workers share a sphere of legal vulnerability, and for many New Yorkers, particularly Asian and Latino undocumented workers, the policing of immigration and sex work operates as a single apparatus. Groups like Red Canary Song, Make the Road New York, and the coalition I organize with, Decrim NY, see the issue of sex work criminalization as, in part, a question of immigration policy. In some contexts, the continued criminalization of sex work is a tool of the state that is used to target workers whose immigration status may limit their access to legal employment. Mamdani cannot meaningfully protect migrants while enforcing the criminalization of work that some rely on to survive.

Sex work and its decriminalization were a hot-button point of debate during the course of the mayoral election. Mayoral candidate and former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo held a press conference in August 2025 to assert that if Mamdani were elected, New York would become the “prostitution capital of the country.” As the local news outlet Hell Gate explained at the time, Cuomo based this assertion on Mamdani’s past “support for state-level legislation that would decriminalize sex work in New York … a bill supported by over a dozen other state legislators in the city.”

A couple of months later, scaremongering about the possible decriminalization of sex work also featured prominently in the AI-generated anti-Mamdani ad that Cuomo’s campaign released and then rapidly removed from its official X feed on October 22. The ad deployed a slew of racist and sexist tropes, including an AI-generated simulation of Mamdani throwing rice into the air and consuming it with his hands, and AI-generated characters concocted to raise fears that Mamdani’s platform could unleash violence and crime in the city, including a Black man in a keffiyeh shoplifting, a white man terrorizing a woman in a rundown apartment, and a caricatured pimp wearing a cartoonish fur jacket, purple silk shirt, and black fedora. In one scene, the AI-generated pimp – a Black man who appears to be a mish-mash of tropes from 1970s crime films and racist tabloid fantasies — says, “Sure, [Mamdani] said multiple times we need to defund the police, but that was just a metaphor.” Later, the pimp flings open the door of an unmarked white van to reveal a group of slumped, light-skinned women, mascara running down their faces, red lipstick smeared, covered in bruises, one with a cigarette drooping from her fingertips.

This scene directly employs the centuries-old stereotype of “white slavery,” the myth that men of color (in the U.S., particularly Black men) threaten the sexual purity of white women, and further, that they enable and perpetrate sex trafficking. The trope and its variants – for example, the hypersexualization of Asian women – have been utilized for political purpose since at least the late 19th century, directly leading to the passage of the Page Act in 1875, the first legislation to restrict immigration in United States history. As a result of its implementation, Chinese women were nearly unilaterally barred from entry into the U.S. on the presumption that they were sex workers and, in the minds of legislators, carriers of disease. Cuomo’s usage of this specific stereotype, not to mention the bald bigotry of the rest of the ad, showed a campaign comfortable embracing the racist political strategies that have repeatedly been used in this country since its inception. Importantly, this framing also suggests that all sex workers are victimized, ignoring the fact that sex trafficking and consensual sex work are profoundly distinct.

In response to Cuomo’s scaremongering, Mamdani softened his rhetoric on sex work rather than doubling down on his earlier support for decriminalization. In an interview with Urdu News on October 11, Mamdani reiterated that he has never supported legalization of sex work, but declined to endorse its decriminalization. “What I have spoken about,” he clarified, “is the need for us to focus on tackling sex trafficking across the city and ensuring that there is no tolerance for violence against women.” While these are commendable goals, they are misdirections that fail to acknowledge that consensual sex workers deserve adequate labor conditions and protections, which are primary goals of decriminalization legislation.

Mamdani has historically been an outspoken endorser of one of the decriminalization movement’s main rallying cries, asserting in a 2021 video from his tenure as councilmember that sex work is work. In the same video, in which he cast his vote for the repeal of the Walking While Trans law, he stated with conviction: “Our streets are not dirty because of sex workers,” clarifying instead that “our streets are dirty because our city and state has systematically been cutting the budget of our brothers, sisters, and family beyond the binary in the sanitation department.”

In the lead-up to the election, however, Mamdani’s record on sex work was patchwork regarding his position on the decriminalization of sex work, despite the fact that he had previously been a sponsor of Cecilia’s Act. Though he appeared to support decriminalization in a September GoodDay New York interview, he has skirted overt endorsement in later statements. In response to a direct question about decriminalization during the second mayoral debate, Mamdani declined to affirm that he would support a legislative shift regarding sex work. He answered more ambiguously that he “[does] not think that we should be prosecuting women who are struggling who are currently being thrown in jail, and then being offered job opportunities. I think we should be actually providing those kinds of opportunities at the first point of interaction.”

Though in general arrests of sex workers have declined over the past decade, those workers who have remained the most visible, street-based and undocumented workers, particularly those in Queens, have been repeatedly targeted by “public safety” campaigns. In October 2024, former Mayor Eric Adams and Councilmember Francisco Moya launched “Operation Restore Roosevelt” as part of the Adams administration’s “Community Link” initiatives. Though the stated goal of Operation Restore Roosevelt is improved “quality-of-life” along the Roosevelt corridor, it has primarily targeted consensual sex workers, nearly 400 of whom were arrested and stripped of income between the launch of the initiative in October 2024 and June 2025. Though the administration claims to provide, as Adams has suggested, “the resources [sex workers] need as they move from a life of [sic] on the street,” in reality, many are simply cast into the city’s underfunded shelter system. Arrests disproportionately affect sex workers of color: Over 90 percent of the workers represented by the Queens Defenders and Legal Aid Society on prostitution charges are Asian and Latinx. The targeted nature of this strategy makes clear that Operation Restore Roosevelt is not simply a question of “quality of life” policing, but rather immigration policy in cheap disguise.

Mamdani has provided little clarity regarding his current intentions around policing of sex work, though he has suggested that he will follow in the footsteps of former mayor Bill de Blasio, by which he seems to mean encouraging a minimal enforcement approach to prostitution charges. After years of advocacy for a decarceral strategy, Mamdani spent much of the tail end of his campaign making public efforts to repair his relationship with the police department, explicitly apologizing to officers and quoting Eric Adams in a statement, arguing that we “need not choose between” social justice and public safety.

Truthout contacted Mamdani’s administration but did not receive a response by publication time.

The mayor is not alone in facing decision-making around sex work. A bill passed earlier this year by the New York state legislature aims to provide immunity for sex workers who are witness to or victims of a crime. Through 2025, the law dictated that sex workers who attempt to report crimes can themselves face arrest for prostitution-related offenses, as has been documented by legal advocacy groups like Brooklyn Defender Services and the Legal Aid Society. The bill prompted bipartisan support and emphasized a key paradox of the current legislative framing: Violent crime is enabled by sex work criminalization, rather than reduced by it.

In a somewhat surprise decision given that she is at the outset of an election year, Gov. Kathy Hochul signed the immunity bill just before Christmas, stamping a win in the books for sex workers’ rights. But pressure for full decriminalization is still needed: Immunity legislation protects workers purely on the basis of prostitution charges, neglecting to shield them from other potentially associated crimes. This means that sex workers who report crimes must conform to the impossible standards of the “perfect victim” — effectively excluding undocumented and other at-risk workers from the protections it aims to establish.

Mamdani, like Hochul, sits at a crossroads regarding policing of sex work. It is an open question whether or not he will avoid the trap into which many progressive politicians have previously fallen: the abandonment of the vulnerable constituencies when faced with the task of governance. What history makes clear is that progressive platforms often struggle to convert to policy for their voters on the margins. But Mamdani’s election was an obvious marvel, a sign that the political imagination of New Yorkers is alive and well.

Though the mayor cannot rewrite state law, his forthcoming administration has an opening to demonstrate that when he says he speaks for the city’s 3 million immigrants, he means migrants of all professions – an opening to protect those at the ledge of precarity, workers whose human rights are assailed along multiple vectors. In practice, Mamdani can discontinue policies like Operation Restore Roosevelt, and he can make good on promises to follow the direction of Brooklyn and Manhattan District Attorneys in minimizing sex worker arrests. He can hold firm to rhetoric that unequivocally supports the need for rights, not rescue, and he can unambiguously endorse the decriminalization movement.

As Decrim NY founder Cecilia Gentili, after whom Cecilia’s Act is named, wrote concerning her experience as a sex worker, first in Argentina and then in the U.S., “I faced constant harassment and violence, especially from la policía. So, I left my home to come to the United States, thinking things would be different. But when I got here, I had no more luck.” Gentili underscores what is at stake in this moment: whether New York will continue to treat migrant sex workers as expendable, or whether it will finally reckon with the harm produced by their criminalization.

This article was originally published by Truthout and is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Please maintain all links and credits in accordance with our republishing guidelines.