In modern Slovak politics, few words carry as much weight as “Gorilla”. It is shorthand for a period when business and politics appeared to merge behind closed doors — and for a scandal that has never truly been resolved.

The affair dates back to the mid-2000s (December 2005-March 2026), when Slovakia’s intelligence service secretly monitored a Bratislava flat used by Jaroslav Haščák, a senior partner in the Penta investment group. Over several months, conversations were recorded that later suggested informal bargaining over state influence, party funding and post-election power.

At the time, Slovakia was preparing for a parliamentary election that would bring Robert Fico and his Smer party to government for the first time. One of the voices captured by the surveillance was Fico’s — making him the only figure from the recordings who remains at the centre of Slovak politics today.

Related article

Slovak politics gripped by Gorilla file

Read more

From public outrage to legal dead end

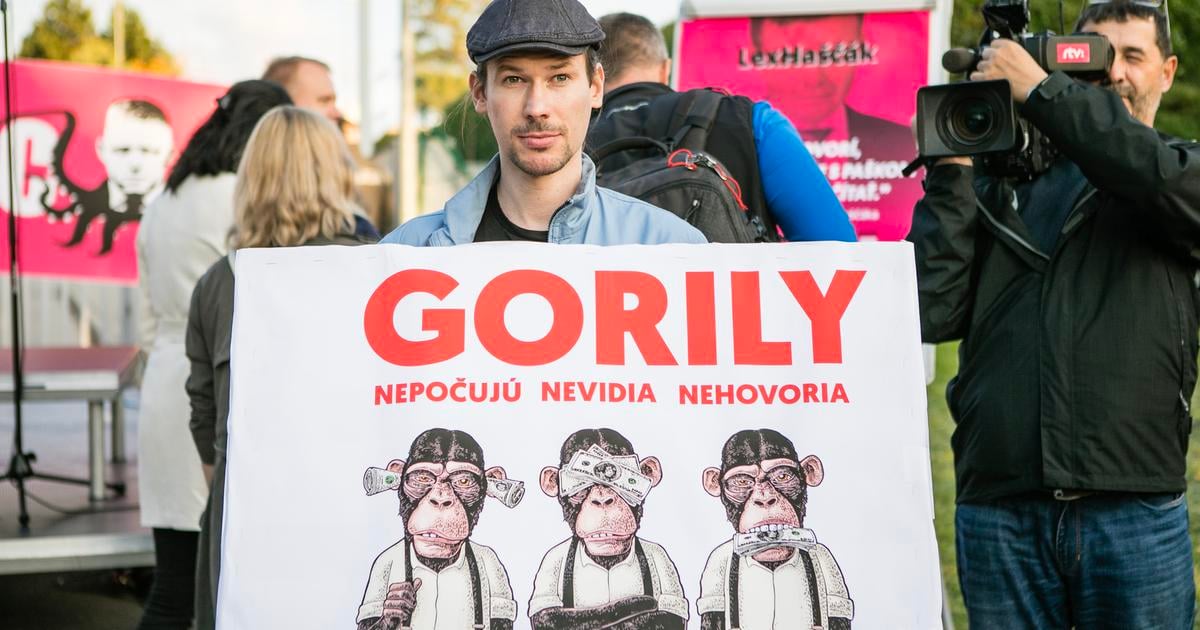

For years, the existence of the operation was unknown outside the security services. When details emerged in late 2011 through an anonymous online leak, the reaction was explosive. Public trust collapsed, protests filled city squares and the promise of a political reckoning hung in the air.

That reckoning never came.

Investigations dragged on through changing governments and shifting prosecutors. Files grew thicker, while outcomes remained elusive. By the time Slovakia was shaken again — this time by the murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kušnírová in 2018 — Gorilla had already become a symbol of institutional paralysis rather than accountability.

Today, the Gorilla case occupies an unusual legal limbo. Police and prosecutors insist that it remains formally under investigation, describing the proceedings as ongoing and non-public. No details are released, and officials decline to comment on timelines or direction.

In practice, however, the room for legal action has narrowed almost to nothing. Charges against the main figures were withdrawn in 2024 after prosecutors concluded that earlier accusations were not supported by evidence. Most of the alleged acts are now beyond the statute of limitations, making prosecution impossible even if wrongdoing were established.

Related article

Gorilla recording has been leaked online

Read more

A case that endures without closure

The final blow came from the courts. Slovakia’s Constitutional Court ruled that the original surveillance had been unlawful, ordering the destruction of the recordings and removing any remaining prospect of their use in court.

The state later issued an apology to Haščák for unlawful prosecution and detention. No comparable gesture was made towards a public that had been promised answers.

Fico, who returned to office again in 2023, long avoided confirming whether he had met Haščák in the monitored flat. That ambiguity ended only after leaked audio surfaced online in 2019, confirming the encounter and offering a rare glimpse into the transactional language of power at the time.

As Slovakia approaches the 20th anniversary of the Gorilla affair in 2026, there is little expectation of renewed momentum. The specialised institutions that once pursued the case have been dismantled, the evidence has been declared illegal, and the alleged crimes have aged out of the legal system.

Yet Gorilla persists — not as an active scandal, but as a political memory. It resurfaces whenever questions arise about who really exercises influence, how accountability is avoided, and why some truths, even when widely known, never lead to judgement.