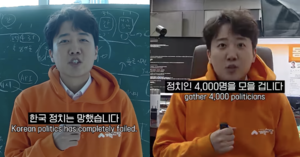

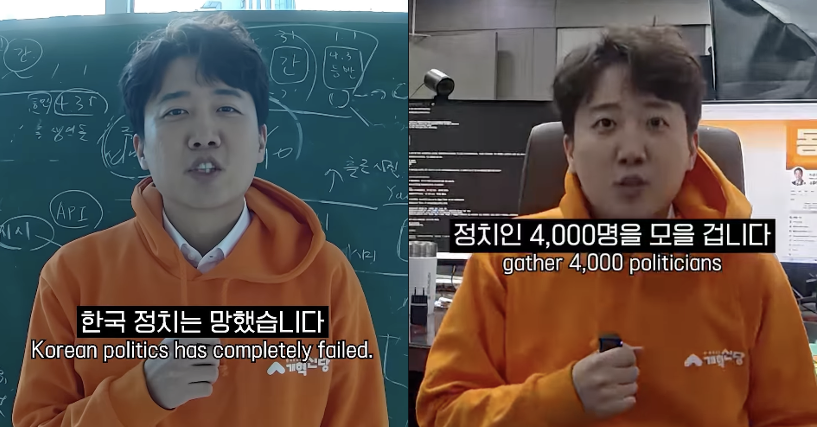

In a video uploaded to Rep. Lee Jun-seok’s Instagram account on Friday, the chair of the minor opposition Reform Party says “Korean politics has completely failed” (left), while calling for the recruitment of 4,000 political candidates (right). (Screenshots from Lee’s Instagram)

In a video uploaded to Rep. Lee Jun-seok’s Instagram account on Friday, the chair of the minor opposition Reform Party says “Korean politics has completely failed” (left), while calling for the recruitment of 4,000 political candidates (right). (Screenshots from Lee’s Instagram) Attention is turning to the high cost of running for public office in South Korea after Lee Jun-seok, head of the minor opposition Reform Party, pledged to allow candidates to run in local elections with just 990,000 won ($670).

In a video uploaded to his Instagram account Friday, Lee said, “In the Reform Party, you can run in a local election with 990,000 won,” and said that the party will recruit 4,000 political candidates, and criticized what he described as entrenched political practices.

“Korean politics has completely failed,” Lee said in the video. “Many politicians think shouting is the same as competence.”

“Those of you watching this video could do politics better than they ever have,” he added. “That’s why anyone in the Reform Party can run for office with 990,000 won.”

In a separate Facebook post, Lee said running for office has long been out of reach for ordinary citizens. “As a result, politics has been left to those with money, time and connections,” he added.

His remarks drew renewed attention amid mounting controversies over nomination-related donations involving the ruling Democratic Party of Korea.

Under South Korean election law, candidates are required to pay a statutory election deposit to the government when registering. The amount varies by election, ranging from several million won for local council elections to tens of millions of won for local government chief contests.

In practice, however, the financial burden of running for office rarely ends with the government deposit.

Candidates also typically face costs tied to the nomination and primary process — including screening fees, interview and document review charges, and expenses associated with internal primaries. Additional costs arise after nomination, such as the production of campaign materials.

Excluding the state deposit, running for local council seats under major parties often requires tens of millions of won, largely due to these party-side nomination and primary-related expenses.

Lee’s proposal focuses on cutting these additional costs imposed by political parties, not the government-mandated deposit.

The Reform Party said it will waive all party-side fees, including screening and review charges, and move the entire nomination process online.

“A system in which candidates must repeatedly visit party headquarters and spend millions — sometimes tens of millions — of won on screening fees and party dues needs to change,” a party official said.

The party also said it plans to minimize the cost of producing campaign materials. However, optional campaign expenses — such as campaign vehicles and paid election staff — would not be covered, meaning total spending could still vary depending on individual campaign strategies.

During the 2022 local elections, both the People Power Party and the Democratic Party reportedly collected several million won per primary candidate in screening and review fees.

Through such nomination-related fees, the two major parties are reported to generate more than 10 billion won in revenue after local elections, even after excluding direct campaign-related expenditures.

Political analysts note that these fees have become a routine part of party finances, particularly during local elections, which involve thousands of candidates nationwide.

Park Sang-pyung, a political commentator, said nomination fees have traditionally served multiple purposes.

“Parties incur real costs during primaries and screenings: interviews, document reviews, and in some cases public opinion surveys,” Park said. “Screening fees help cover those expenses and also function as a source of party revenue.”

He added that the fees are also intended to discourage frivolous or insincere candidacies by imposing a minimum financial commitment.

Still, Park said Lee’s pledge could resonate with younger voters and those fatigued by existing political structures.

“Lee is signaling that he wants to elevate younger people and appeal to voters who feel worn down by traditional politics,” Park said. “For wealthier candidates, these costs may not matter much, but for younger people, they are a real barrier.”

Park cautioned that the Reform Party, as a minor party, faces structural limits.

“For a third or fourth party, even finishing third or fourth is difficult, and reaching 8 or 9 percent of the vote is not easy,” he said. “By lowering entry costs, Lee is trying to present a different kind of party without appearing to run a political ‘business.’”

Lower costs, however, could also constrain campaign visibility.

“If major parties run 10 campaign trucks, a Reform Party candidate may run one,” Park said. “That can affect competitiveness. Even so, reducing the risk and upfront cost of running for office is something worth applauding.”

He also noted that nomination deposits should not be viewed solely in negative terms.

“Because election expenses are reimbursed based on vote share, the system can motivate candidates to campaign seriously,” Park said.

Under current law, candidates are eligible for government reimbursement of election expenses depending on their vote share. Candidates who win or receive at least 15 percent of the vote are reimbursed in full, while those receiving between 10 and 15 percent are reimbursed for half their expenses. Candidates who fall below 10 percent receive no reimbursement.

In last year’s presidential election, Lee, who ran as the Reform Party candidate, spent more than 28 billion won but failed to qualify for reimbursement after securing 8.34 percent of the vote.

By contrast, President Lee Jae Myung, then the Democratic Party candidate, spent 53.5 billion won, while Kim Moon-soo of the People Power Party spent 45 billion won. Both qualified for cost recovery under ethe lection law.

flylikekite@heraldcorp.com