©

EPA/PAOLO AGUILAR

|

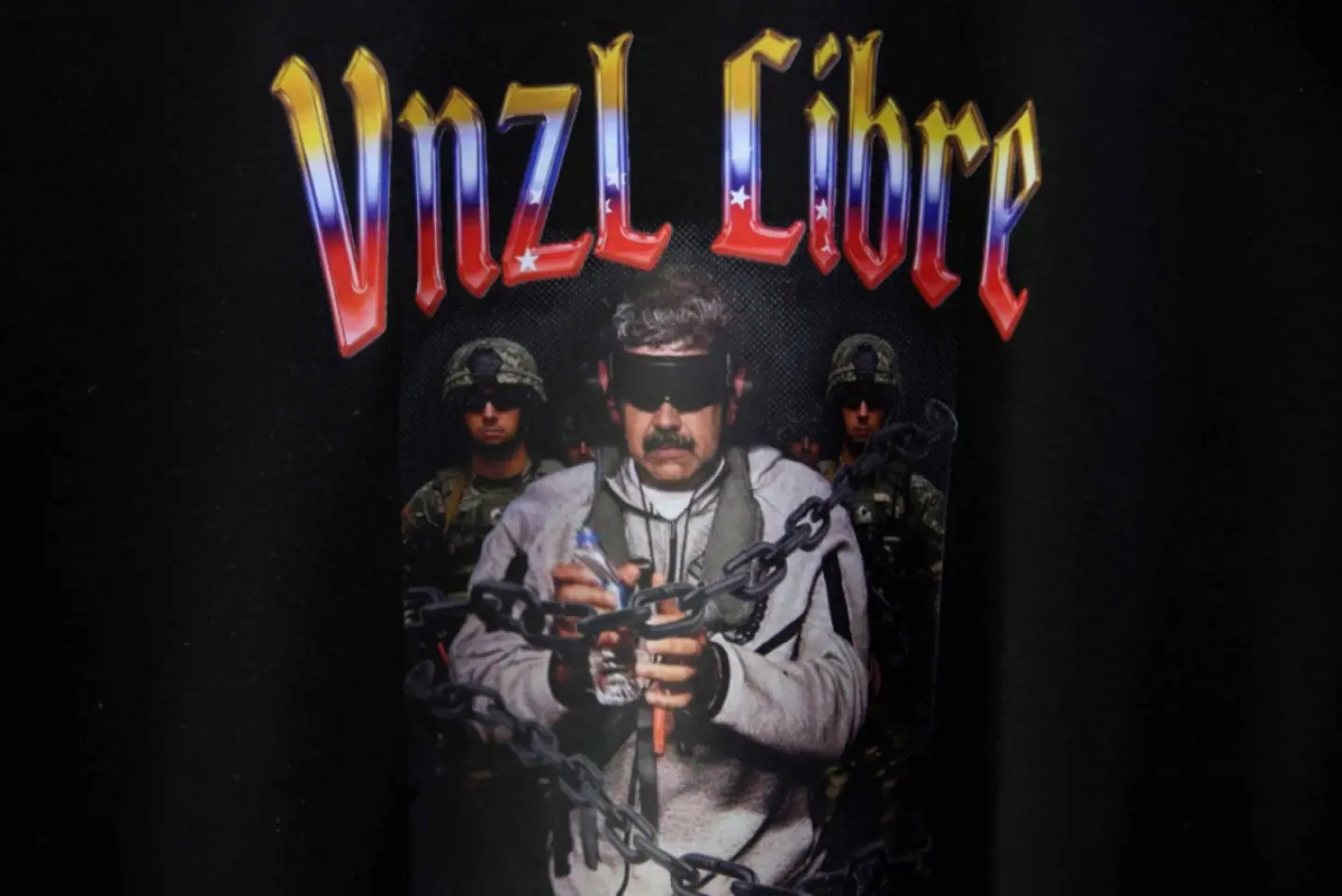

A T-shirt with an image of the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro in Lima, Peru, 06 January 2026.

The U.S. military’s lightning operation to seize Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro – despite months of threats leading up to it – shocked many observers, but the oil markets barely flinched at the news, underscoring Venezuela’s diminished role in global supply. However, the geopolitical and economic repercussions are significant, especially for Russia. Moscow had cultivated Caracas as a like-minded ally under Hugo Chávez and Maduro, bonding over anti-Western rhetoric and oil-fueled state capitalism. Now the Kremlin faces the loss of this foothold and must reckon with what Venezuela’s turbulent transformation portends for Russia’s own position – both internationally and at home.

Political Fallout: A Vanishing Ally in Latin America

Washington’s intervention in Venezuela sent a clear signal of U.S. resolve. In Moscow, it is seen as a brazen reassertion of the Monroe Doctrine – the U.S. enforcing its will in its “backyard” – marking a return to open great-power spheres of influence. The swift precision of the operation, which removed a key Kremlin ally from power in mere hours, stood in stark contrast to Russia’s failed attempt to rapidly topple Ukraine’s government in 2022. Authoritarian regimes worldwide perceived the Caracas raid as a warning of how far the United States is willing to go against autocrats.

For Russia, the political blow is twofold. First, Moscow appears unable to protect or avenge an allied regime, eroding its image as a reliable patron. The Kremlin offered only tepid condemnation after U.S. commandos whisked Maduro away – a notably muted response given prior pledges of “full support” for Caracas. This impotence underscores Russia’s predicament: already overstretched by the grinding war in Ukraine and constrained by sanctions, it could only watch from the sidelines.

Second, Russia is losing a valuable ideological and strategic partner. Under Chávez and Maduro, Venezuela reliably aligned with Moscow in international forums. Caracas also served as a platform for Russian influence in the Western Hemisphere. With Maduro removed and Venezuelan government likely to pivot West, the Kremlin’s reach in Latin America shrinks. Russia is being pushed back toward its own neighborhood at the very moment it had sought room to maneuver globally. In essence, Moscow’s geopolitical chessboard is down one figure. The distraction of a Venezuela crisis may briefly draw U.S. attention from Ukraine, but any silver lining for the Kremlin is tempered by the stark demonstration of U.S. power and Russia’s inability to counter it.

Economic Entanglements: Oil, Sanctions and the “Shadow Fleet”

The political relationship between Moscow and Caracas has been deeply anchored in oil. Over the past two decades, the Kremlin poured an estimated $17 billion into Venezuela through loans and investments, primarily via Rosneft. In return, Caracas repaid much of this debt in oil. By the late 2010s, Rosneft was effectively reselling Venezuelan crude – roughly 13% of Venezuela’s exports – to markets like the United States, India, and China. These shipments, often routed through intermediaries, allowed Venezuela to monetize its oil under sanctions and let Russia deepen its foothold in the hemisphere’s oil trade.

At the same time, the Kremlin had a paradoxical incentive to limit Venezuela’s oil comeback. Analysts note that Moscow quietly preferred Venezuela’s output to remain constrained, lest a flood of Venezuelan crude crash global prices – which would hurt Russia’s own oil revenues. Indeed, Venezuela’s production had already plummeted over the past decade due to mismanagement and sanctions, averaging only about 1.1 million barrels per day last year (a mere 1% of world output). That decline turned Venezuela into a minor player in supply terms – hence why oil prices barely moved on news of the U.S. intervention. But for Russia, Venezuela’s stagnation was something of a strategic asset: it kept oil prices higher and left an opening for Rosneft to broker oil deals without unleashing a competitor.

Now, U.S. actions threaten to unravel these economic arrangements. The naval blockade imposed by the Trump administration on tankers near Venezuela and the high-seas seizures of sanction-busting ships represent a new, more aggressive phase of enforcement. The captured Marinera tanker, for example, was part of the “shadow fleet” of vessels that Russia, Iran, and Venezuela have used to covertly ship oil in defiance of Western sanctions. In December, the Marinera evaded an initial U.S. Coast Guard attempt by turning off its transponder and even hastily repainting a Russian flag on its hull to claim Russian protection. Nonetheless, it was ultimately boarded by U.S. special forces in the North Atlantic. This marked the first U.S. interdiction of a Russian-flagged oil tanker – a bold move that Moscow protested diplomatically.

For Russia, the economic stakes in Venezuela’s regime change are high. Billions in loans are at risk of default now – money Moscow is unlikely to ever recoup. High-profile projects are in jeopardy. Russian firms that once helped Venezuela dilute and export its extra-heavy crude could be elbowed out by American companies if sanctions on Venezuela ease. Indeed, U.S. officials have signaled a strong interest in reviving Venezuela’s oil industry under new leadership – a development that would bring Western majors into fields where Rosneft and Gazprom once staked claims.

Transition Lessons: Venezuela as a Cautionary Tale for the Kremlin

Perhaps the most sobering aspect of Venezuela’s crisis for Russia lies in the comparative trajectory of their regimes. Venezuela under Maduro exemplified a late-stage “rentier” autocracy propped up by oil wealth – but crucially, it was not a classic one-man dictatorship. Scholars describe it as a “network” or coalition-based authoritarianism, where power was distributed among multiple elite factions tied together by oil rents. Removing Maduro, therefore, did not automatically collapse the Venezuelan regime’s authority. Instead, his ouster has merely triggered a recomposition of the ruling coalition. In Venezuela’s case, that fragmentation could mean a period of protracted low-intensity conflict and competing zones of control masquerading as one country.

The Venezuelan scenario is a vivid warning for Russia’s leadership. Vladimir Putin’s regime, like Maduro’s, is heavily reliant on commodity rent (oil and gas) to maintain elite loyalty and social stability. That oil dependence creates a superficially strong but internally brittle system. During boom times, abundant petrodollars allow the state to buy loyalty and expand the ruling coalition, tolerating multiple semi-autonomous elite fiefdoms. However, when the oil rent shrinks – due to price crashes or sanctions – those previously cohesive elite networks can turn into competing camps.

For Russia, which still depends on hydrocarbons for a large share of state revenue, the parallel is unsettling. The economic freefall Venezuela experienced after 2014 – GDP shrank by about 75% in seven years, returning the country to poverty levels unseen in decades – shows how quickly a petrostate can unravel under external pressure and misrule.

Russia’s economy is larger and somewhat more diversified; it has not suffered anything on Venezuela’s scale. But with oil prices now off their peaks and Western sanctions tightening, the Kremlin is effectively managing a diminishing rent pool similar to Maduro in his later years. The war in Ukraine further strains resources, while an inevitable generational turnover looms among Russia’s elite.

All this means the Kremlin must contemplate its own “transit” – a future political transition – under far less favorable circumstances than it once hoped. Moscow’s planners can draw direct lessons from Caracas. One is that a strongman’s sudden exit does not guarantee regime change if the system has morphed into groups of interests.

Venezuela’s predicament underscores the perils of extreme rent-dependency. Russia has long prided itself on a “fortress economy” and the ability to weather sanctions. Yet Venezuela’s decade-long depression demonstrates that even vast oil reserves cannot save an economy from collapse if governance is poor and isolation deepens. In fact, oil wealth can mask underlying decay until a breaking point is reached.