Across India, private companies are making commitments to invest billions of dollars in green ammonia technology (Supplementary Table 1). Most investments are directed to producing green ammonia as a fuel. Still, there is also growing interest in its potential as a fertilizer and for direct incorporation into human food and livestock feed.

Green ammonia projects for marine shipping fuel and export are eligible for financial incentives under the green hydrogen mission of the Solar Energy Corporation of the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy and the advanced technology industrial policies of the states of Odisha, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra. The first facility in the world to produce more than 1000 metric tonnes per year of green ammonia was commissioned at Bikaner, Rajasthan, in 2021, and several Indian companies are at various stages of approval to build plants with production capacities ranging from 0.4 to 2.9 million metric tonnes per year (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, industry initiatives propose to lower the carbon intensity of steel production by earmarking 37% of all future government steel procurement to require green ammonia energy6.

For green ammonia-based fertilizer production, the Solar Energy Corporation of India has issued a tender for procuring 0.75 million metric tons per year of green ammonia fertilizer (approximately 4% of domestic production)2. The Indian government has several reasons for investing in green ammonia-based fertilizers.

First, although over 80% of the nitrogen fertilizers used in India are synthesized domestically, over 80% of the natural gas used for their synthesis is imported (44 million standard cubic meters per day)2. Not only is this importation costly (about $9 billion U.S. dollars per year)2, it also creates vulnerability to food insecurity due to price volatility and supply chain disruptions caused by pandemics and wars. Second, fertilizers produced from green ammonia could be a viable substitute for a portion of the urea used in Indian agriculture. Urea makes up about 85% of the nitrogen fertilizers used in India and is heavily subsidized, costing the government about $17 billion U.S. dollars annually2. Third, the adoption of green ammonia could help India reach its greenhouse gas emission reduction commitment by reducing carbon dioxide emissions from domestic nitrogen fertilizer synthesis (currently 45 million metric tonnes CO2 per year)4. The Indian government offers credits for reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and for reducing current subsidies of urea fertilizers. Green ammonia could qualify for both, which could help offset the costs of constructing and operating facilities, as well as the necessary infrastructure, training, and outreach to gain acceptance by farmers or other users.

Green ammonia fertilizer production could be developed either in distributed small-scale operations at the community level7 or in large-scale plants (Supplementary Table 1). Small-scale green ammonia production units have been deployed in Canada, the United States, and Kenya, providing valuable learning opportunities for what might work in India. Some adaptations may be needed for the implementation of green ammonia-based fertilizers, as there is limited experience in India with using gaseous anhydrous ammonia or aqueous ammonia as fertilizer (aqueous ammonia is a solution of 10–20% ammonia dissolved in water). Therefore, application methods that are adoptable by farmers must be developed. Application to the soil surface could result in significant ammonia emissions, so soil injection technologies are needed. Alternatively, green ammonia can be converted to other forms of fertilizer, including urea, but at additional costs of securing a CO2 source8.

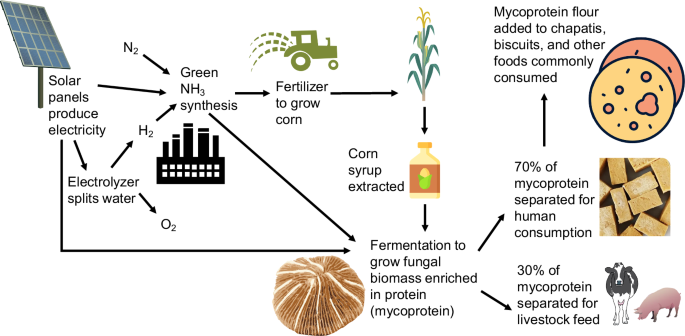

In addition to fertilizer production, green ammonia could enable the production of alternative proteins for human and livestock consumption, thereby circumventing some of the current large nitrogen losses to the environment from Indian croplands1,9. For example, fungi grown with green ammonia and corn syrup (or other carbon sources) in fermentation reactors have been processed into an easily digested, protein-rich mycoprotein flour (Fig. 1) that can be used as a supplement to other flours for baking chapatis, which is an important source of calories in the typical Indian diet. When enriched with mycoprotein, chapatis and similar foods could help address the growing burden of diabetes as well as protein malnutrition. Mycoprotein has the advantage of adding protein to foods that are already widely consumed in India, thus not requiring a behavioral change. About 70% of the mycoprotein is fit for human consumption, and the remaining 30% would be best used for livestock feed supplementation. By producing animal feed protein directly from green ammonia, and thus relying less on growing crude crop protein, livestock production could utilize nitrogen more efficiently10.

Schematic of ACME Group’s production of mycoprotein using green ammonia synthesized with renewable energy as the source of nitrogen (https://www.acme.in/sustainable-foods) for enriching chapatis and other human food and as a livestock feed supplement. Renewable energy is used to split water into hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2) gases. The H2 is combined with dinitrogen (N2) gas from the atmosphere to synthesize ammonia (NH3). The mycoprotein icon was provided by the ACME Group. The chapati and corn syrup icons are from image:Flaticon.com. All of the other icons are from the Integration and Application Network (ian.umces.edu/media-library).

Ammonia is widely used as a refrigerant for cooling of crop storage facilities in communities throughout India, with opportunities to improve the energy efficiency and reduce the greenhouse gas footprint of those facilities11. Hence, markets and experience already exist for shipping, storing, and handling ammonia. Green ammonia could penetrate the refrigerant market as the costs decline. With India’s extensive potential solar resource, green ammonia production could be widely distributed, thus reducing transportation costs of refrigerants and fertilizers7.