Europe’s oil market is becoming increasingly exposed to disruption as security risks rise along export routes used by Kazakhstan, which the European Union has long viewed as a reliable alternative to Russian supply.

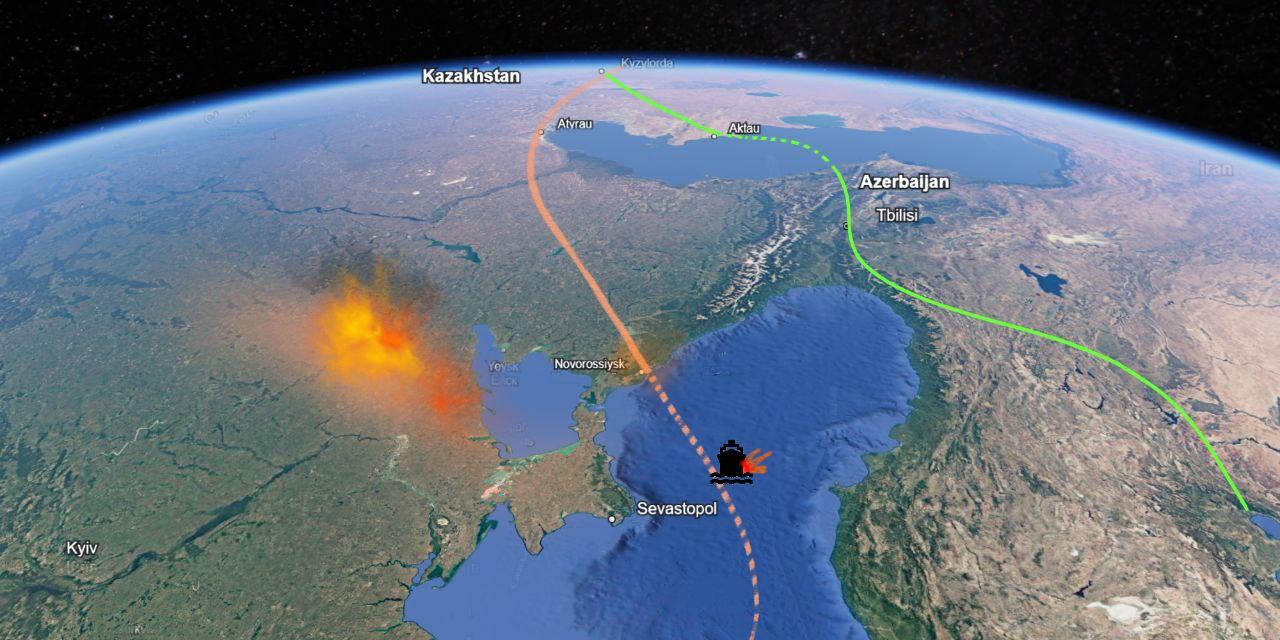

Kazakhstan produced roughly 1.8 million barrels per day in 2024 and exported the bulk of that volume. More than 80% of its crude exports move through the Caspian Pipeline Consortium, or CPC, which links oil fields in western Kazakhstan to Russia’s Black Sea port of Novorossiysk. From there, tankers ship the oil mainly to European refiners. Under normal conditions, the pipeline carries roughly 1.3 million barrels per day, making it one of the most important single supply routes for non-Russian crude entering Europe.

Recent events have shown how sensitive European markets are to any disruption along that corridor. On January 14, Bloomberg reported that oil prices in Europe strengthened after shipments of CPC Blend fell short of expectations. Traders cited reduced availability of the light, low-sulfur crude, which is favored by European refiners, forcing buyers to seek alternative grades at higher prices. Despite the recent tightening, traders say the market has so far absorbed disruptions without severe shortages, reflecting high inventories and flexible refinery operations, though that buffer could narrow if attacks persist.

That supply pressure followed a series of security incidents in the Black Sea, where commercial shipping and port infrastructure have faced growing risks since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Although Kazakhstan is not a party to the conflict, its exports depend on transit through waters and facilities that have become increasingly vulnerable.

On January 13, drone attacks struck oil tankers near the approaches to Novorossiysk as vessels waited to load Kazakh crude. The incidents prompted heightened security measures and contributed to temporary loading constraints at the CPC terminal. While no casualties were reported, the attacks raised concerns about further disruptions.

Following the attacks, war-risk insurance premiums for tankers operating near Black Sea export terminals have risen sharply, according to shipping and insurance industry data. Higher premiums and tighter underwriting standards have increased freight costs for CPC Blend cargoes and made some shipowners more reluctant to call at Novorossiysk, adding another layer of uncertainty even when physical infrastructure remains operational.

The incidents have also raised questions among European policymakers about whether Ukrainian strikes near Black Sea export infrastructure risk undermining broader energy and diplomatic interests.

Echoing these concerns, on January 14, Kazakh lawmaker Aydos Sarym also warned that attacks affecting CPC-linked infrastructure risk harming Kazakhstan’s economy and the interests of its partners. “Such actions create serious risks not only for Kazakhstan, but for countries that depend on these energy supplies,” Sarym said. “I think the U.S. and our other partners should work together to pressure Ukraine to choose its goals.”

While Kyiv has not publicly claimed responsibility for the recent attacks affecting the Novorossiysk area, analysts note that Ukraine views pressure on Russian export hubs as a way to weaken Moscow’s ability to finance the war. At the same time, disruptions to the CPC carry political weight because the pipeline moves non-Russian crude that remains exempt from EU sanctions. This overlap has complicated the picture for EU governments, which continue to support Ukraine militarily while seeking to avoid supply shocks and higher prices at home.

These risks also have massive consequences for Kazakhstan’s production. Earlier, in December 2025, industry and government data showed that output fell by around 6% after a late-November strike limited exports through the Yuzhnaya Ozereevka loading point, forcing producers to slow or cut production at major fields, including Tengiz, the country’s largest oilfield. At the same time, exports of CPC Blend crude dropped to their lowest levels in over a year as the terminal operated with limited capacity due to damage and maintenance work, illustrating how quickly pipeline and shipping constraints can translate into lower production when transport routes are impaired.

For the European Union, the issue goes beyond short-term market volatility. Since 2022, the bloc has worked to reduce dependence on Russian oil while avoiding global supply shocks, with Kazakh crude playing a significant role in that strategy. According to Eurostat Comext, in 2024, the largest suppliers of crude oil to the European Union included the United States, Norway, and Kazakhstan, with the latter accounting for about 11.5% of the bloc’s imports.

EU officials have repeatedly stated that Kazakh oil transiting Russia is not subject to EU sanctions, provided it is clearly certified as non-Russian, a policy which reflects both legal considerations and a broader effort to maintain access to alternative supplies without undermining sanctions aimed at Moscow.

Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said the country should not be associated with the conflict in Ukraine, stressing its role as a stable energy supplier to Europe: “We emphasize that the Republic of Kazakhstan is not a party to any armed conflict, makes a significant contribution to strengthening global and European energy security, and ensures uninterrupted energy supplies in full compliance with established international standards.”

Western corporate interests are closely tied to the security of the CPC route. Major U.S. and European energy companies hold stakes in Kazakhstan’s largest oil fields, including Tengiz and Karachaganak. Chevron and ExxonMobil are key partners in Tengiz, while Eni, Shell, and TotalEnergies have long-standing investments across the sector. Production from these fields depends on uninterrupted access to export infrastructure linked to Novorossiysk.

The vulnerability of the CPC route stems not only from geography but from ownership and control. The pipeline and its Black Sea terminal are operated by a consortium that includes Russian state-linked entities alongside Western energy companies, complicating efforts to insulate Kazakh exports from wider security risks surrounding Russian-controlled infrastructure. Russia also has an interest in keeping CPC flows running, since the pipeline generates transit revenues and helps sustain activity at the Novorossiysk port, even as the broader security environment around the Black Sea remains unstable.

Disruptions therefore affect not only Kazakhstan’s state revenues, but also European energy supply and the operations of Western firms. They also tighten oil markets at a time when spare global capacity remains limited, amplifying price sensitivity.

The European Union has limited direct leverage over security conditions in the Black Sea. Any military involvement would raise legal and political challenges, given the ongoing war and the presence of multiple naval actors in the region. Instead, EU efforts have focused on diplomatic engagement on freedom of navigation, coordination with insurers to prevent sudden withdrawal of coverage for non-sanctioned cargoes, and technical work to strengthen tracking and certification of oil shipments. EU officials have previously warned that sustained disruption to Black Sea energy routes could undermine efforts to stabilize fuel prices and inflation across the bloc, particularly in southern member states.

For its part, Kazakhstan has been seeking to reduce reliance on a single export corridor. It has increased shipments of crude oil via the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline as part of efforts to diversify export routes, with state operator KazTransOil reporting increased volumes through the Caspian Sea and BTC direction following disruptions to the CPC system.

Even so, expanding alternative routes would require significant investment, coordination with neighboring states, and years of construction, limiting Kazakhstan’s ability to reduce exposure in the near term.

“These attacks add urgency to the case for expanding Trans-Caspian infrastructure,” Laura Linderman, director of programs, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute, American Foreign Policy Council, told The Times of Central Asia. “Kazakhstan has been working to diversify its export routes but remains heavily dependent on a corridor that runs through Russian territory and waters, a vulnerability Astana has long highlighted. Officials and analysts in Kazakhstan increasingly argue that Western partners have been insufficiently responsive to these concerns, even as Europe relies on Kazakh crude, making continued dependence on Russian transit a growing strategic contradiction.”

For now, Europe remains heavily exposed to the security of Kazakhstan’s Black Sea exports. As long as the conflict in Ukraine continues and maritime risks persist, even suppliers viewed as politically separate from the war face growing uncertainty. Recent market movements show how quickly disruptions affecting Kazakh oil can feed through to European prices and energy security, underscoring the strategic importance of safeguarding export routes that sit outside the war but remain exposed to it.

The European Union was contacted for comment, but had not responded at the time of publication.