A leading voice in global ecology, Camille Parmesan explores the link between biodiversity and a warming world. In this conversation, she looks back on field discoveries and her path into scientific exile, asking how living systems adapt to climate change—and why conservation strategies must be rethought to meet it.

The Texas-born ecologist first made her name by showing, definitively, that climate change was reshaping a wild species: Edith’s checkerspot butterfly. Lately, she’s known not only for her work on life’s future in an overheated world and the Nobel Peace Prize shared with IPCC colleagues, but also for her life as a scientific refugee in Europe.

Twice, she moved countries to keep working in a political environment open to climate research—leaving Trump’s America in 2016, then post-Brexit Britain. She now lives in Moulis, Ariège, directing the CNRS Station for Theoretical and Experimental Ecology.

Talking with her clarifies how to protect a conservation landscape full of surprises, how to handle growing species mixing, and how to answer ambient climate skepticism.

The Conversation: Your early habitat work on Edith’s checkerspot quickly drew international attention. How did you actually show a butterfly could be affected by climate change? What tools did you use?

Camille Parmesan: A pickup truck, a tent, a butterfly net, strong reading glasses to spot tiny eggs and leaf damage from caterpillars, plus a notebook and pencil. In the field, you don’t need more than that.

Before heading out, I spent a year touring U.S. museums—then Canada, London, and Paris—collecting every record I could on Edith’s checkerspot. I wanted precise locations like ‘One mile [1.6 km] from Parsons Road, June 19, 1952’. The species lives in small, sedentary populations. Back then, nothing was digitized, so I read pinned specimens and wrote down collection notes by hand.

Edith’s checkerboard. © Singer and Parmesan, Provided by the author

In the field, I visited each site during the brief flight season—about a month—timing surveys so they’d count. You start by looking for adults. If none appear, you keep going: eggs, silk from young caterpillars, feeding scars from larvae emerging after hibernation…

Edith’s checkerboard butterfly in its larval stage on Penstemon leaves. © Singer and Parmesan, Provided by the author

You also assess the habitat: enough healthy host plants or nectar sources for adults? If not, I excluded the site. I wanted to isolate climate effects from other pressures like habitat loss or pollution. On big sites I checked more than 900 plants before I considered the census complete.

The Conversation: When you go back to those sites now, decades later, do you see things you couldn’t at first?

C. P.: I look for things I didn’t forty years ago—and that my husband, Michael C. Singer, didn’t fifty years ago. For example, eggs are now laid slightly higher, a small shift that’s a crucial adaptation to climate stress.

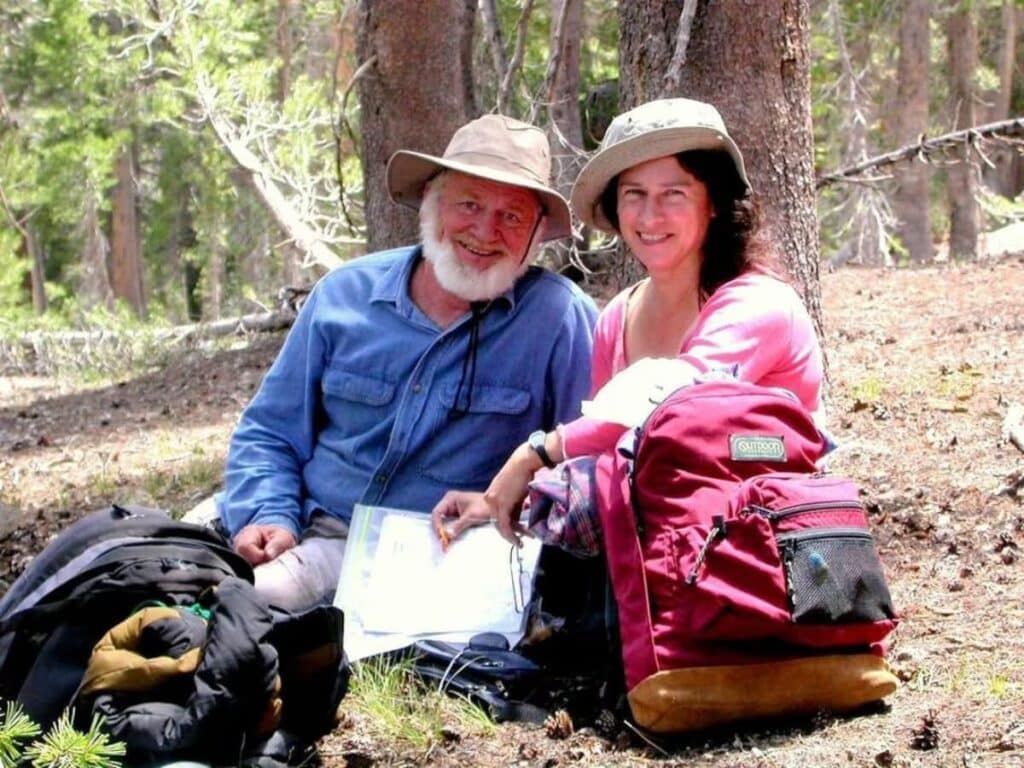

Camille Parmesan and her husband and colleague, biologist Michael C. © Singer. Provided by the author

They’re higher because ground temperatures have soared. Last summer we recorded 78°C at the surface. A falling caterpillar dies. You can watch butterflies touch down and instantly lift off—it’s too hot for their feet—then fly to vegetation or even land on you.

Early on, I’d never have guessed egg-laying height mattered. That’s why biologists must watch the organism, its habitat, and truly pay attention. I see young scientists rushing to grab specimens for lab work or genetics. That’s fine, but without time in the field, lab results won’t connect to nature.

Edith’s checkered pattern (female) and eggs laid under a leaf. © Singer and Parmesan, Provided by the author

The Conversation: We now know many species must shift ranges to survive, yet it’s hard to predict where they’ll persist. What should we do? What lands should be preserved?

C. P.: That question haunts conservation biologists. Go to a meeting and you’ll see people get depressed because they don’t know what to do.

Color differences in Edith’s Fritillary butterflies at low (left) and high (right) altitudes. Research on other butterfly species shows that darker wing colors are an adaptation to colder climates, as they help the butterflies bask in the sun. © Singer and Parmesan, Provided by the author

We need to move from strict protection to something like an insurance portfolio—flexible plans that adjust as field realities unfold.

Don’t lock into a single plan. Start with multiple approaches because you don’t know which will work.

We just published a paper arguing that ecosystem management should borrow decision frameworks from unpredictable arenas like economics or urban water policy. Planners there don’t know if next year is wet or dry, so they manage uncertainty.

Modern computing lets you simulate 1,000 futures and ask what happens if you take a given action. Some scenarios look good, others bad, some mixed. You then hunt for ‘robust’ actions—those that perform well across the most futures.

Using standard bioclimatic models for 22 species across ~700 scenarios, we found that protecting only current sites dooms most organisms. Just 1–2% of futures keep a species in the same place.

So we protect current sites and also places where models say the species occurs 30%, 50%, 70% of the time. From these futures, you can choose combinations that cover most likely persistence zones—often blending traditional reserves with new areas outside today’s range. Protecting current sites is good, but often not enough.

Bigger is better. Keep protecting ecosystems—especially high-diversity regions. Species will leave, others will arrive, and a hotspot can remain a hotspot because complex terrain and microclimates sustain turnover.

Globally, we need 30–50% of land and sea as relatively natural habitat, without always demanding strict protection.

Between them, build corridors so organisms move without being killed. In crop belts—say, wheat—crossing can be fatal. Thread semi-natural habitat through fields. If there’s a river, create wide buffers so organisms can travel. It doesn’t need to be perfect habitat; it just mustn’t kill them.

Private yards matter too. Leave a patch unmowed with ‘weeds’. Nettles and brambles make corridors for many animals—road verges can do the same.

Incentives help: tax breaks for leaving areas undeveloped. The broader point for scientists is not to put all eggs in one basket. Don’t rely on one favorite model or just current sites.

You also can’t save every potential site—too costly. Instead, build the strongest portfolio you can within budgets and partnerships so we don’t lose the species entirely—giving it places to recolonize once the climate stabilizes.

The Conversation: Hybridization is another growing concern. How do you see this increasingly common phenomenon?

C. P.: Species are on the move as never before, and they’re meeting. Polar bears pushed off sea ice now encounter brown bears and grizzlies—and sometimes produce fertile hybrids.

Conservation once resisted hybridization to preserve differences in behavior, appearance, diet, genetics. Hybrids are often less fit, so people separated species—even killing hybrids.

Climate change makes that a losing battle. We should widen our lens: protect a wide variety of genes.

Populations rich in genetic variation can adapt rapidly. Fighting hybridization may strip away the raw material for adaptation. To keep post-change diversity—if that day comes—we should safeguard as many genes as possible, even if we lose what we call a distinct species. Polar bears and grizzlies offer evidence: past warm periods brought contact and hybridization; polar bears later reappeared faster than evolution from scratch would allow, likely from genes retained in grizzlies.

The Conversation: Non-scientists see nature’s remarkable adaptations, yet also a global collapse in diversity. How do those realities fit together?

C. P.: Today’s change is fast. Each species has a fairly fixed physiological niche—its ‘climate space’ of precipitation, humidity, and dryness. Push past limits and organisms die, for reasons we still don’t fully understand.

Species often adapt to human-driven stressors like metals or light and noise, thanks to existing genetic variation. City sparrows and pigeons, for instance, manage.

But for climate change, most organisms lack the variation to survive. New variation comes from hybridization—or mutation, which is slow. Adapting to what’s coming could take one to two million years.

In the Pleistocene, with 10–12°C swings, species moved rather than evolve in place. Go back to the Eocene—extreme CO₂ and heat—and some species vanished because they couldn’t move far enough. Evolution on climate timescales doesn’t happen in centuries; it happens over hundreds of thousands to millions of years.

The Conversation: You’ve written that populations highly exposed to climate change can still resist extinction—so we should protect them, reduce other stressors, and monitor adaptation. An example?

C. P.: Edith’s checkerspot again. It has distinct subspecies, genetically and ecologically. In southern California, the Quino checkerspot is especially imperiled.

Quino’s checkerboard butterfly laying its eggs on Plantago erecta. © Larry Gibert and Michael C Singer, Provided by the author

It’s taken heavy hits from warming and drought—the tiny host plant dries too fast—and urban sprawl from San Diego and Los Angeles wiped out habitat. Despair would be understandable.

In the early 2000s, my husband and I helped plan habitat for Quino, after ~70% declines.

We warned that defending only low-elevation sites would fail. Why not add higher sites where they didn’t yet occur?

Higher elevations had potential host plants—different species than usual, but similar to ones used elsewhere. We brought lowland butterflies to the new host; they accepted it. No evolution required—just moving upslope.

So we protected present sites and higher ones so the population could shift.

That happened. Luckily, the highest areas belonged to the U.S. Forest Service and Indigenous communities willing to help.

We also restored a vernal pool—shallow clay-bottomed basins that fill in winter and host a whole community, including fairy shrimp. The Quino host plant grows along their edges. Pools dry by April, just as the butterfly enters dormancy; seeds do too, restarting in November.

Vernal pool at Carrizo Plain National Monument in California. © Mikaku/Flickr, CC BY

San Diego had bulldozed many pools for development. The endangered species office rebuilt one on a trashed lot, lined it with clay, and planted vegetation, including Plantago erecta.

Within three years, the restored site supported almost all the target threatened species—most arrived on their own, including the Quino.

Soon after, we found Quino at higher elevations as well. Honestly, I was stunned. The butterfly usually stays put; distances were modest, but movement isn’t its habit.

The Conversation: Was there a biological corridor between the two areas?

C. P.: A few scattered houses with lots of natural brush in between—no real host plants for Quino. But it was enough for flight, nectar stops, and, crucially, not getting killed. A corridor doesn’t have to support a population; it just mustn’t kill it.

The Conversation: You’ve moved to continue your work amid political headwinds. French media have covered you as a scientific refugee. Has U.S. media shown similar interest?

C. P.: Colleagues and acquaintances asked how I did it—visas, language, and so on.

But U.S. media weren’t interested. Coverage came from Canada and Europe.

Americans don’t grasp the extent of damage to academia, education, and research. Even my family struggles to see it—some are Trump supporters—but you’d think the media would notice.

Outlets have covered structural harms to universities—book bans, efforts to shape curricula to a political line. But they don’t talk about the people leaving. There’s an arrogance that no one would leave the ‘best country’ to work elsewhere.

Historically, U.S. researchers enjoyed huge funding from agencies, donors, NGOs. That flow has, in many areas, simply stopped.

The Conversation: To cut through denial, it’s tempting to highlight human health. You’ve worked on that—does it resonate?

C. P.: I’ve always cared about human disease. I nearly went into medicine. As soon as we documented large species shifts, I thought: diseases will shift too. My lab studies how climate change alters the spread of diseases, their vectors, and reservoirs. One student traced leishmaniasis moving north in Texas.

Within the IPCC, we noted malaria, dengue, and three other tropical diseases appearing in Nepal for the first time in historical records—linked to climate, not agriculture.

New diseases are emerging in the Far North, mainly affecting Inuit communities—easy for politicians to minimize. In Europe, the tiger mosquito is expanding in France, bringing pathogens.

Leishmaniasis already exists in France—one species so far, but four or five more are projected soon. Tick-borne illnesses are rising and spreading northward. Europe is already seeing climate’s health impacts; people just don’t realize it.

The Conversation: Your family includes Trump supporters. How do you handle that?

C. P.: We simply don’t talk about it—same for politics and religion. We value harmony over division. If climate comes up, it gets hard fast, reminding us why we avoid it. I won’t risk my family. If they want to learn more someday, they know where to find me.

I’ve also worked with people whose beliefs differ from mine. In Texas, I worked with the National Association of Evangelicals. We agreed on protecting biodiversity—God’s creation to them; for me, humans shouldn’t wreck the Earth. I’m an atheist; it didn’t matter. We made a video series on warming’s effects. It worked beautifully.

Interview by Gabrielle Maréchaux

This article appears as part of the ANR’s 20th anniversary. Camille Parmesan is a laureate of the ‘Make Our Planet Great Again’ priority research program, run by ANR for the State under France 2030. ANR supports basic and applied research across disciplines and serves as the main operator of the France 2030 plan in higher education and research.