The excavation of an ancient Roman basilica in Fano, Italy. Credit: Italy’s Ministry of Culture

The excavation of an ancient Roman basilica in Fano, Italy. Credit: Italy’s Ministry of Culture

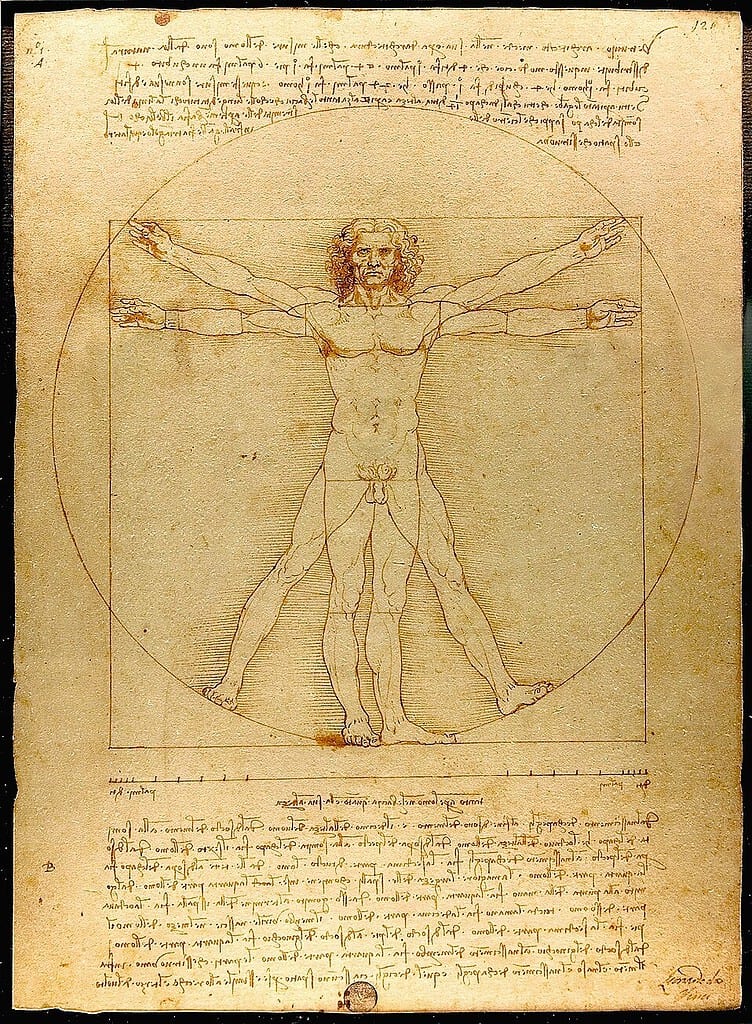

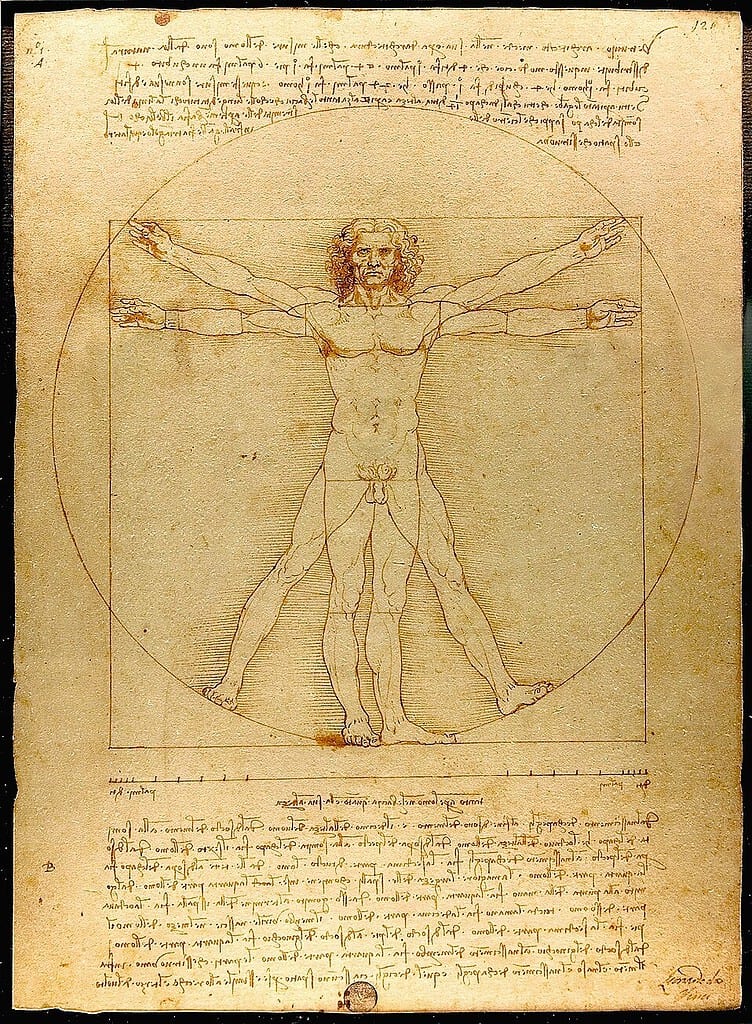

For well over 2,000 years, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio has existed as a kind of myth in the history of architecture and civil engineering. We know him as the “father of architecture,” the author of the only surviving architectural treatise from classical antiquity, and the man whose concepts of proportion inspired Leonardo da Vinci’s famous Vitruvian Man.

Yet, despite his massive influence on how the Western world builds, we had never found a single brick or column that we could say, with certainty, he placed himself.

That changed this week in the Italian seaside city of Fano.

In a discovery that Italian officials are calling the “discovery of the century,” archaeologists excavating a site in the city center have unearthed the remains of a 2,000-year-old basilica. The find isn’t just another Roman ruin; these are the remains of a building Vitruvius described in his own writings. The ghost of Western architecture finally has a home.

A Masterpiece Hidden in Plain Sight

Credit: Italy’s Ministry of Culture

Credit: Italy’s Ministry of Culture

The discovery happened during urban redevelopment work on the Piazza Andrea Costa in the heart of Fano. As layers of modern paving were peeled back, a massive structure began to emerge. The scale was immediately impressive.

Archaeologists uncovered a rectangular footprint bordered by magnificent columns. The measurements were staggering. On-site analysis revealed these columns spanned five Roman feet in diameter — roughly 60 inches or 150 centimeters — and likely stood about 49 feet (15 meters) high.

Credit: Italy’s Ministry of Culture

Credit: Italy’s Ministry of Culture

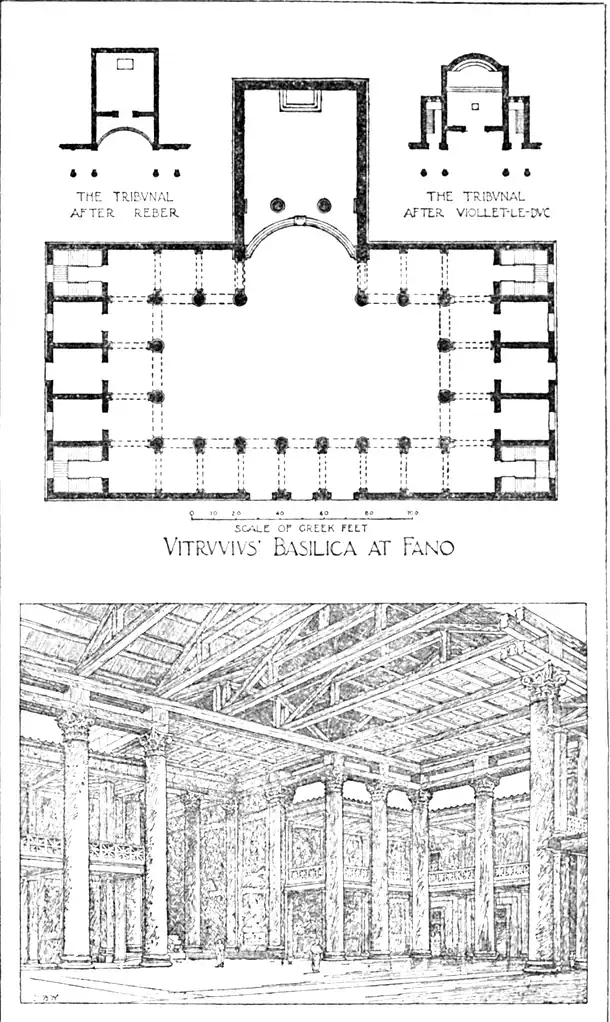

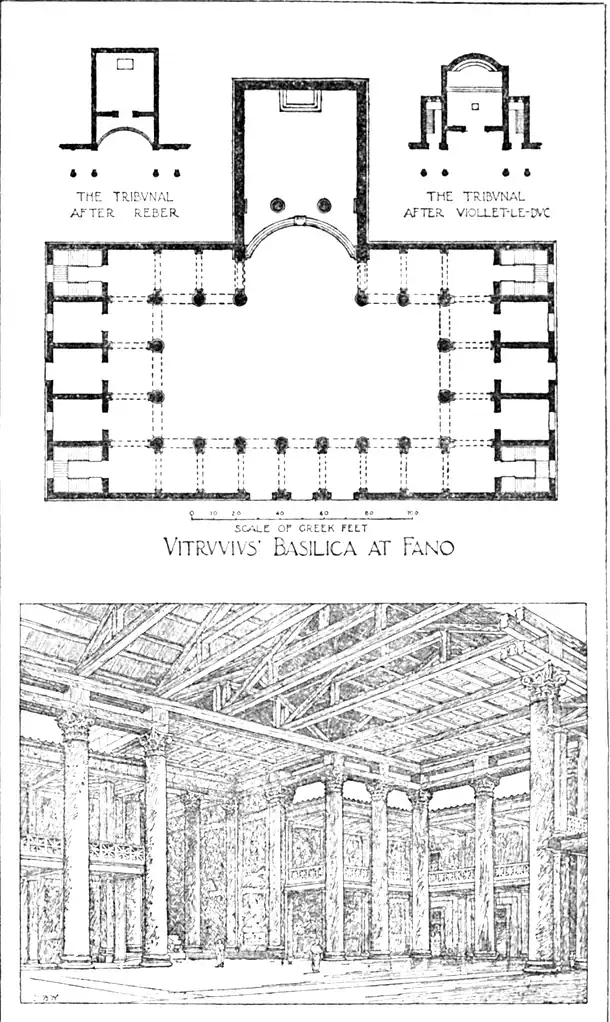

The layout of the building featured columns arranged in a precise rectangle, with eight columns running along the long sides and four defining the shorter ones. This arrangement rang a bell for historians familiar with Vitruvius’s major treatise, De Architectura (The Ten Books on Architecture).

In Book V of his opus, written in the 1st century B.C.E., Vitruvius alluded to a specific project he “carried into execution in the Julian colony of Fano.” He detailed a basilica with specific dimensions for porticos and columns. The ruins in Fano weren’t just similar to his description — they were a perfect match.

Digging by the Book

Rendering from the early 20th century and floor plan of Vitruvius’s basilica in Fano. Credit: public domain.

Rendering from the early 20th century and floor plan of Vitruvius’s basilica in Fano. Credit: public domain.

The confirmation of the site came through a remarkable feat of predictive archaeology. Because Vitruvius had written down the specifications of his Fano basilica so precisely, archaeologists could essentially use his ancient book as a treasure map.

The structural system described by Vitruvius involved pilasters and corner supports designed to hold massive weight. When traces of the initial columns appeared, the team used the treatise to calculate exactly where the building’s fifth corner column should be located.

They dug at the predicted spot, and the column was there.

“There are few certainties in archaeology,” said Andrea Pessina, the area’s archaeological superintendent, “but we were impressed by the precision” of the match. Pessina noted that the site represents an “absolute match” between the dirt and the text.

Usually, archaeologists dig to find out what was built. In this case, they knew what was built — they just had to prove it still existed.

The Man Behind the Manual

To understand the weight of this discovery, it helps to understand Vitruvius. Active in the 1st century B.C.E., he was an engineer and architect for Caesar and Augustus. His work, De Architectura, is the cornerstone of classical architectural theory, founded on the famous triad of firmitas, utilitas, venustas (strength, utility, and beauty).

Vitruvian Man (Italian: L’uomo vitruviano) is a drawing by the Italian Renaissance artist and scientist Leonardo da Vinci, dated to c. 1490. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Vitruvian Man (Italian: L’uomo vitruviano) is a drawing by the Italian Renaissance artist and scientist Leonardo da Vinci, dated to c. 1490. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

His influence stretches far beyond his own lifetime. During the Renaissance, his writings were rediscovered and zealously studied by figures like Mariano di Jacopo and Francesco di Giorgio Martini. But his most famous student was born over a millennium after he died: Leonardo da Vinci. Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (c. 1490) is a direct visual translation of the proportions of the human body as described in Vitruvius’s Book III.

Despite this legacy, Vitruvius remained an enigma. We knew what he thought, but not what he built. That’s now changed with the Fano basilica, which helps put a place to the name.

“After centuries of waiting and study, what for a long time was transmitted only through the written word has been transformed into a concrete, tangible, and shareable reality,” said Fano’s mayor Luca Serfilippi.

A New Era for Fano

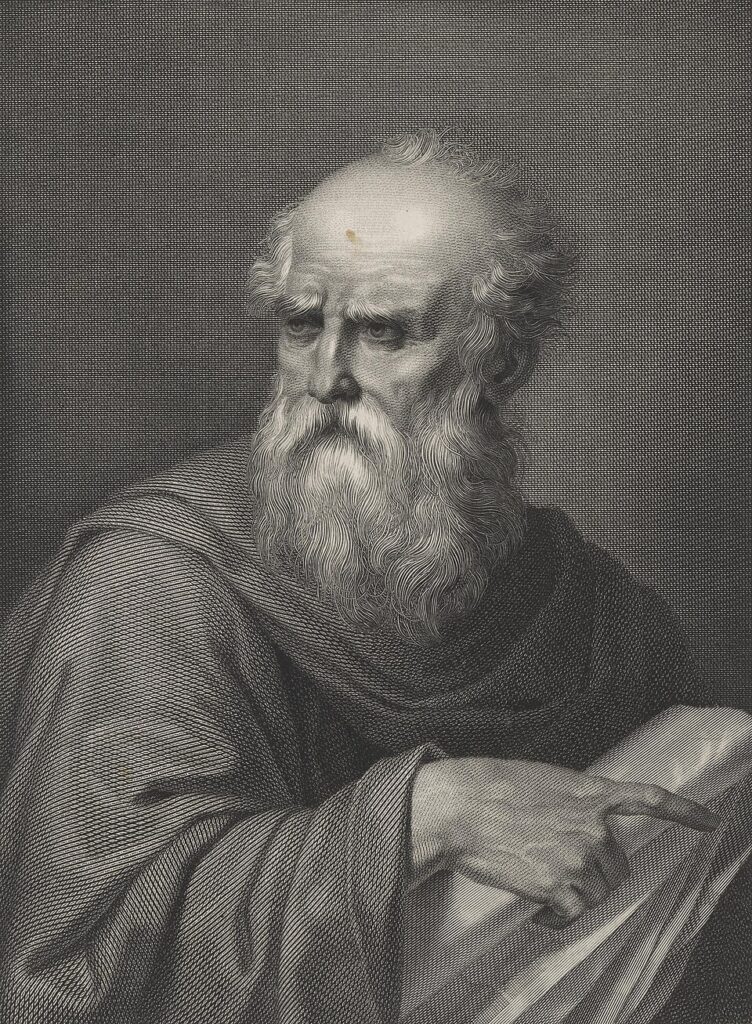

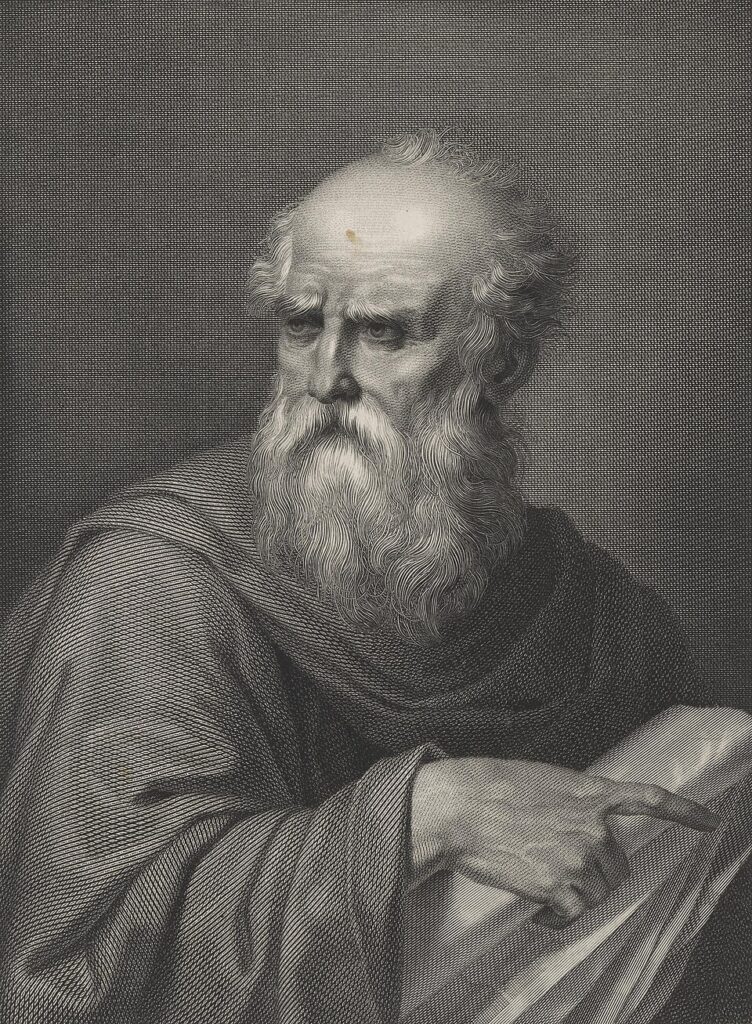

Portrait of Vitruvius (80 BC – 15 BC), circa 1830. Credit: Jacopo Bernardi (engraver); Vincenzo Raggio (painter).

Portrait of Vitruvius (80 BC – 15 BC), circa 1830. Credit: Jacopo Bernardi (engraver); Vincenzo Raggio (painter).

The identification of the basilica has sent shockwaves through the Italian cultural sector. For Fano, a city in the Marche region, this is a transformative moment. The city has a Vitruvian Study Centre that has promoted the architect’s work for thirty years, but they have never had a physical monument to rally around until now.

Hints of this discovery began surfacing in 2022, when a dig at the nearby Via Vitruvio revealed wall structures and high-status marble pavements. However, the confirmation of the basilica’s layout seals the deal.

“Today in Fano, a fundamental piece of the mosaic that preserves the deepest identity of our country was discovered,” Italian Culture Minister Alessandro Giuli stated. He added that the find is “something that our grandchildren will be talking about” and that “the history of archaeology and research is now divided into before and after this discovery.”

Preserving the “Father of Architecture”

Now that researchers have found the building, the race is on to protect it. The site is currently a delicate ruin in the middle of a modern city. The Italian Cultural Ministry has already begun talks to gain UNESCO-protected status for the site.

Technical plans are being drafted to ensure the fragile masonry can be preserved while potentially opening the site to the public. The goal is to musealize the area. Essentially, it would turn a construction zone into a pilgrimage site for lovers of history and design.

Regional President Francesco Acquaroli noted that the discovery “compels us to rewrite part of the history of Fano.” It is a sentiment echoed by experts across the field. For centuries, scholars have searched for this building. Now that the stone has spoken, we have a new tool to understand the origins of the buildings we live and work in today.

As Mayor Serfilippi put it, “I feel like this is the discovery of the century, because scientists and researchers have been searching for this basilica for over 500 years.”