In the hours after two babies tragically lost their lives in an unlicensed and overcrowded daycare facility in the largely ultra-Orthodox Jerusalem neighborhood of Romema on Monday, top Haredi politicians were quick to point fingers.

Members of both the Ashkenazi United Torah Judaism party and the Sephardic Shas blamed the deaths on the attorney general’s cancellation of daycare subsidies for fathers who don’t serve in the army in July, following a 2024 High Court decision designating draft exemptions for Haredi men as illegal.

Yet, the existence of unlicensed facilities, unqualified personnel, and a lack of adherence to educational and security standards for babies and toddlers has plagued the Haredi community, and Israel as a whole, since long before the current school year.

“Early childhood education is a real challenge for all Israeli society because Israel is a very young country with a great number of children, but especially for the Haredi community, which tends to have very big and very poor families,” said Dr. Shlomit Shahino Kesler, senior researcher at the Israel Democracy Institute’s Ultra-Orthodox Society in Israel Program.

“According to research we conducted in 2022, only 32% of [Haredi] families send their children to licensed, subsidized daycare, so this is not a problem from the last few months. It goes way back,” she told The Times of Israel over the phone.

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

The State of Israel offers free education to children ages 3 and up. In 2018, a new law placed the Education Ministry in charge of child care for infants and toddlers aged 0-3.

The ministry runs a number of subsidized daycares, which are chronically insufficient. In addition, it requires private daycares with more than six children to obtain a license, while small facilities with fewer than six children are unregulated. For the 2025-2026 school year, the monthly fee for a private daycare could easily reach NIS 5,000 ($1,580).

Rescue and security forces work at the scene of a mass-casualty incident at an unlicensed daycare in Jerusalem’s Haredi-majority Romema neighborhood, on January 19, 2026 (Chaim Goldberg/Flash90)

In 2022, the state comptroller published a report about 0-3 education based on data from 2020 and 2021. According to the report, of the almost 550,000 children under 3, only about 150,000, or 27%, attended a subsidized public daycare, with another 35% in private daycares and 38% kept at home.

The report highlighted that the lack of spots for children was especially dramatic in cities and towns lower on the socioeconomic scale, and particularly in ultra-Orthodox and Arab localities.

In the city of Jerusalem, for example, in 2021, there were about 70,000 children under three, but only 12,300 subsidized spots. Jerusalem is one of Israel’s poorest cities.

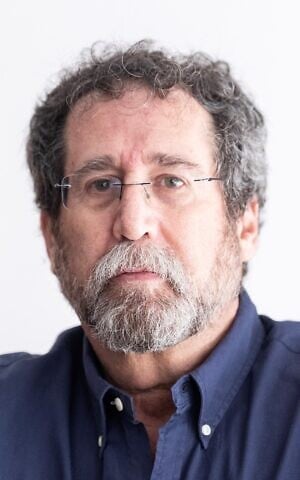

Dr. Shlomit Shahino Kesler, senior researcher at the Israel Democracy Institute’s Ultra-Orthodox Society in Israel Program. (Israel Democracy Institute)

Shahino Kesler noted that it was difficult to estimate how many unlicensed or unsupervised daycare centers operated in the Haredi sector and in Israel in general, given their unofficial status.

To get a clearer picture of the situation, the state comptroller compared the data of employers and employees registered in the sector at the National Insurance Institute and those registered at the Education Ministry.

According to the report, in 2021, there were approximately 4,000 private daycare centers, according to documentation from the National Insurance Institute. However, as of May 2021, over 1,000 of them had not submitted applications for initial approval to the Education Ministry.

Of the applications submitted, only 1% came from daycare centers in ultra-Orthodox communities (and 6% from Arab communities). According to National Insurance Institute records, some 200 daycares operated in Haredi towns, but only 20 applied for a license.

The report also highlighted severe problems with staff training at both licensed and unlicensed facilities.

Some 44,200 caregivers were reported to be employed in public or licensed facilities, but 22,000 of them lacked formal training. Data from the National Insurance Institute suggested that an additional 23,000 caregivers were employed in private centers, at least 11,500 without formal training.

“The data indicate that there are private daycare centers — particularly in localities and neighborhoods with low socioeconomic rankings, as well as in the Arab and ultra-Orthodox communities — about which the [Education Ministry’s relevant] department has no information,” reads the report. “Given the socioeconomic conditions in these localities and neighborhoods, there is concern that the quality of care is inadequate and does not meet the requirements of the law and its regulations, meaning that the children who most need high-quality early childhood education are not receiving it.”

Illustrative: Ultra-Orthodox children in Mea Shearim, Jerusalem, on December 19, 2024. (Chaim Goldberg/Flash90)

The state comptroller also denounced a lack of inspectors to monitor the recognized daycares, suggesting that while the law required a minimum of one inspector for every 100 facilities, the ministry employed only 25 inspectors. According to a statement by the Education Ministry on Monday, the ministry currently employs 59 standard inspectors and six safety inspectors, in addition to a few consultants, for roughly 5,000 recognized facilities.

The report stated that in 2020, the ultra-Orthodox community accounted for 24% of Israeli babies and toddlers but received 52% of the budget for subsidies, while Arab toddlers, also 24% of children under 3 in the country, received only 8%. The document also noted that 60% of Haredi children and 39% of Arab children lived in poverty, and that the employment rate among ultra-Orthodox women stood at 79% and among Arab women at 37%.

Prof. Dan Ben-David. (Courtesy)

Prof. Dan Ben-David, president of the Shoresh Institution for Socioeconomic Research and professor of economics at Tel Aviv University, pointed out that the high level of employment among ultra-Orthodox women must be viewed in the context of the low employment rate among men in the community.

“While employment rates among Haredi women are relatively close to those of Jewish non-Haredi women, they work many fewer hours per week, so they earn less per week,” Ben-David told The Times of Israel in a written message. “Furthermore, their education levels are lower than those of Jewish non-Haredi women, which contributes even further to lowering their wages in comparison with Jewish non-Haredi women.”

“The clincher, of course, is that male Haredi employment rates are abysmal, while those who do work are less educated and work fewer hours than Jewish non-Haredi men,” he said. “Add to that an average of over six children per Haredi family, compared to just two for Jewish non-Haredi families. It is not a coincidence that people who work less, are less educated, and have three times as many children are poor. At what point do they start assuming responsibility for their choices and quit blaming everyone else for their situation?”

Yet, according to Ran Cohen Harounoff, CEO of Early Starters International (ESI), an organization that focuses on early childhood education for vulnerable children and communities in Israel and several other countries, in order to fix the problems brought to light by Monday’s tragedy Israel needs to rethink the way it approaches 0-3 education.

“The main problem is that in Israel and also many other countries in the world, early childhood education is overlooked, especially between birth and age 3,” he told The Times of Israel over the phone. “When Israel decided that the Education Ministry would be responsible for daycares with over six children, that marked a change, but an insufficient one, because most children are in unsupervised frameworks with fewer than six children, and even among the bigger ones, many did not apply for a license, especially in the poorest communities.”

Ran Cohen Harounoff, CEO of Early Starters International (ESI). (Courtesy of Yuval Cohen Harounoff)

Israel also suffers from a lack of qualified personnel.

“There are not enough caregivers who want to work in early childhood, and most of those who do have no training or experience,” Cohen Harounoff said.

He said that a few years ago, ESI worked on a project researching daycares in Jerusalem, especially in the Haredi and Arab communities, which exposed him to daycares in inadequate apartments and even garages.

“I saw a place that charged by the day, NIS 7 [$2.22] a day per child,” he recalled.

Cohen Harounoff said that the Israeli authorities, parents, and media should understand how important early education is and invest the proper resources.

“All research shows that early childhood is the most important time for a child to influence who they will become as a person,” he noted. “I am very afraid that after what happened, they will make a big fuss and try to put a bandage on it, forming a committee or something similar, and in a few weeks, everything will be forgotten.”

Indeed, on Tuesday, the Education Ministry announced that it would establish an inter-ministerial task force, in cooperation with the police, local authorities, the State Attorney’s Office, and additional bodies, to formulate a systemic plan for identifying, enforcing against, and closing private frameworks operating in violation of the law, alongside strengthening monitoring and supervision mechanisms.

“The government should decide that we need a big change, more money for buildings and supervision of daycares, and much higher salaries for the teachers,” Cohen Harounoff said. “A daycare teacher should make at least as much as a high school teacher.”