Writer Judy Lev, a Cleveland transplant who lived in Jerusalem’s Baka neighborhood for 38 years, is putting the beloved locale on display with her new book, an ode to the charming cluster of streets and shops that scores of English-speaking immigrants have called home for decades.

“Bethlehem Road: Stories of Immigration and Exile” (published by She Writes Press and distributed by Simon & Schuster) is a collection of 12 short stories named for the neighborhood’s main artery, and is Lev’s fictionalized take on the people and places she knew during those nearly four decades.

Dividing the stories into four sections, “Immigration,” “Settling Down,” “Family Life” and “Dispersion,” Lev loosely follows her own trajectory on Bethlehem Road through her characters, their complex lives, and the constant motion of the Israeli-Arab conflict.

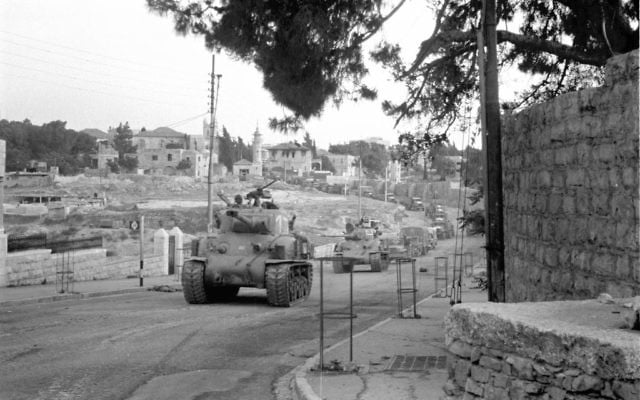

The stories begin in the first days after the 1967 Six Day War, as Baka recovers from the effects of Jordanian shelling.

The book continues with tales told against the background of terror attacks, and as former Arab residents of Baka, a prestigious neighborhood built by wealthy Christian and Muslim Arabs in the 1920s, return to see the homes they fled during the 1948 War of Independence.

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

The stories are also populated, of course, by new immigrants from the United States — Chicago, Ohio, Boston and other places far from the Middle East.

A line of Sherman M-50 tanks and trucks full of soldiers ride towards East Jerusalem to confront the Jordanians on June 5, 1967. (Benny Hadar/Defense Ministry’s IDF Archive)

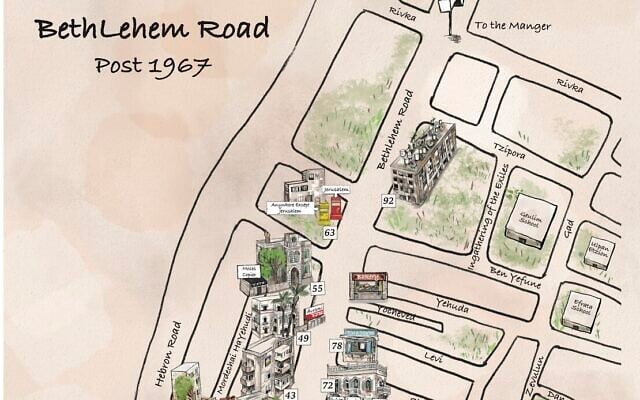

These newcomers are named John and Simon, Helen, Dick and Bonnie, in sharp contrast to locals called Ovadia, Bracha, Boaz and Oren — but sabras and sojourners alike are drawn to this neighborhood of narrow streets and handsome homes, just as Baka’s residents are today.

Lev was one of those new arrivals, having just graduated from university when she came to Israel in the wave of American immigration following the Six Day War.

She trained as a social worker, part of a 13-month course created for new immigrants, and settled in Baka with her then-husband, where they raised their three children.

A residential building in Jerusalem’s Baka neighborhood. (Wikimedia commons/ Ester Inbar)

“There’s something about this neighborhood,” said Lev. “All the needs are supplied. You have everything. You don’t have to go anywhere else. The combination of having buildings that are part commercial and then residential, and then the mixture is just fabulous.”

It was an undeveloped neighborhood when Lev arrived, without sidewalks and with some of the new immigrants living in absorption huts.

Lev’s neighbors included all kinds of newcomers, some of them Holocaust survivors, others pushed out of the Old City as Jerusalem expanded and changed. There was Doda Rosa, who peddled candy from a shack, as well as “the Bulgarian guy” who sold chickens, and Oved, whose falafel shop still stands on Bethlehem Road, albeit with a different owner.

“There was such a charm to it all,” said Lev.

Falafel Oved on Bethlehem Road (Mitch Ginsburg/ Times of Israel)

Lev, who was always writing something, eventually had a column in The Jerusalem Post, featuring personal essays about her life as a mother and American immigrant. She has also taught creative writing.

“I remember writing a poem,” said Lev. “It was in 1967, I was looking out over the Judean Hills to the Dead Sea, and I said, ‘This is my home?’”

She didn’t begin writing the stories found in “Bethlehem Road” until many years later. The book’s final story, which was published in The Kenyon Review in 1991, became a kernel for “Bethlehem Road,” which she worked on when she earned a master’s degree in creative writing at Bar-Ilan University.

A portion of the map included in ‘Bethlehem Road’ by Judy Lev (Courtesy)

Now 80, Lev still speaks about her love affair with Baka — though she left more than 20 years ago, first for Beit Zayit, a village just outside Jerusalem, then for Tel Aviv, and later, Haifa.

“I felt it took me five years to grieve for Baka, for having left Baka,” she said.

While sitting at the cafe next to her former apartment on a weekday afternoon, Lev pointed out neighborhood locations, including the field on nearby Reuven Street where Arab shepherds once let their sheep graze.

“I would cook in the kitchen and look out at the window and see them,” she said.

Jerusalem’s Baka neighborhood during the 1948 War of Independence. (Public domain)

Lev recalled how few Americans there were in those days, and how even after nearly 60 years of life in Israel, she is still an immigrant.

“Not every story is about being an immigrant, but the majority of them are, because it’s so true. For most of your life, you feel like an immigrant, but then there are moments where you don’t,” said Lev.

“I have a very close relationship between immigration and exile,” she said. “Many people immigrate, and they feel like they’re in exile from their original home. So you feel like you’re in exile, but you’re told you’re in your home.”

You appreciate our journalism

You clearly find our careful reporting valuable, in a time when facts are often distorted and news coverage often lacks context.

Your support is essential to continue our work. We want to continue delivering the professional journalism you value, even as the demands on our newsroom have grown dramatically since October 7.

So today, please consider joining our reader support group, The Times of Israel Community. For as little as $6 a month you’ll become our partners while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel

Already a member? Sign in to stop seeing this