The experimental search for 2,5-CT and 2,4-CT was guided by ab initio quantum chemical calculations that derived the main spectroscopic parameters from geometry optimization and harmonic force field analysis (section ‘Theoretical calculations’ and Extended Data Fig. 1). The rotational transitions of 2,5-CT and 2,4-CT in the 8–40-GHz range were observed using a combination of a chirped-pulse Fourier transform microwave spectrometer and a pulsed-discharge supersonic jet (section ‘Laboratory measurements’ and Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3 for details). Molecules were generated by a pulsed discharge in the throat of a 10-Hz supersonic jet using a vapour pressure of thiophenol at room temperature of 25 °C. The experimental settings were optimized by monitoring the production of 2,5- and 2,4-cyclohexadien-1-one generated from the discharge of anisole (c-C6H5OCH3).

In the 8–40-GHz region, 92 and 75 rotational lines of 2,5-CT and 2,4-CT, respectively, were detected, covering quantum numbers up to J = 15 and Ka = 7, as shown in Supplementary Data 1 and 2 (ref. 40). Their rest frequencies, determined with a precision of about 5 kHz, were fitted to an effective Watson-type Hamiltonian in S reduction, which included the rotational and centrifugal distortion constants listed in Table 1. The three rotational constants A0, B0 and C0 and the centrifugal distortion constants DJ, DJK, d1 and d2 were determined by the fit, whereas the centrifugal distortion constant DK was kept fixed to the values obtained by the CAM-B3LYP/cc-pCVTZ calculations41,42. The fit reproduces the experimental frequencies with a root-mean-square (RMS) deviation of 2.8 kHz and 3.3 kHz for 2,5-CT and 2,4-CT, respectively. Based on this analysis, rest frequencies for transitions used in the analysis of the astronomical spectra are predicted with uncertainties sufficiently better than 10 kHz. For the frequency ranges of the spectroscopic survey carried out towards the G+0.693 cloud, this uncertainty corresponds to uncertainties in velocity of less than 0.1 km s−1. This is small compared with the typical linewidths of the molecular emission measured towards this cloud (of ~20 km s−1; ref. 39).

Detection of 2,5-CT in G+0.693

We analysed an unbiased, ultrasensitive broadband spectral survey of G+0.693 carried out with the IRAM 30-m and Yebes 40-m radio telescopes (for details of the observations, see Methods). The observed data were compared with simulated spectra of 2,5-CT generated with the Spectral Line Identification and Modeling (SLIM) tool within the MADCUBA software package43, under the assumption of constant excitation temperature, here referred to as local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE). We note that the intermediate H2 volume densities (104–105 cm−3) in G+0.693 (refs. 39,44) result in the subthermal excitation of molecular emission, thus yielding excitation temperatures (Tex = 5–20 K, which is lower than the kinetic temperature Tk = 50–150 K; ref. 39). Unlike massive hot cores or low-mass hot corinos—where numerous rotational transitions, including those from vibrationally excited states, are observed—only low-energy rotational transitions in the ground vibrational state are detectable in G+0.693, significantly reducing the levels of line blending and confusion due to the excitation temperatures. Consequently, with the current sensitivity, we anticipate the detection of a few tens of transitions of 2,5-CT at these low excitation temperatures.

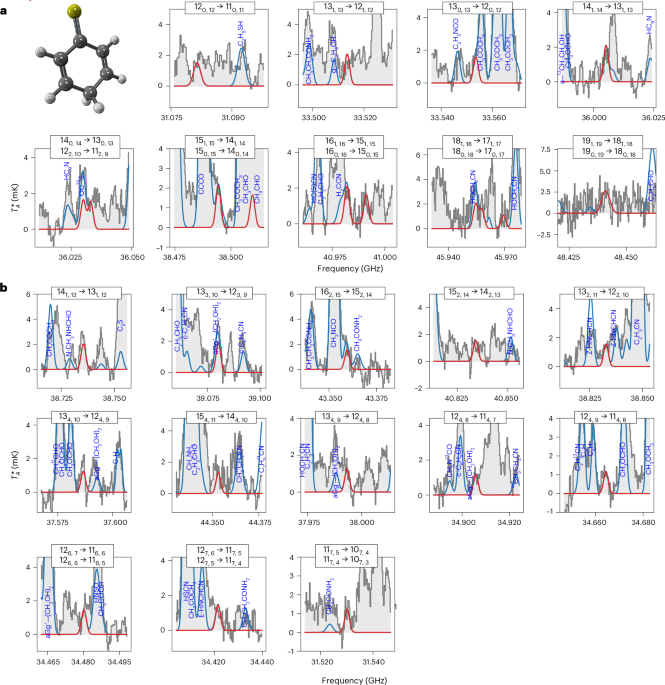

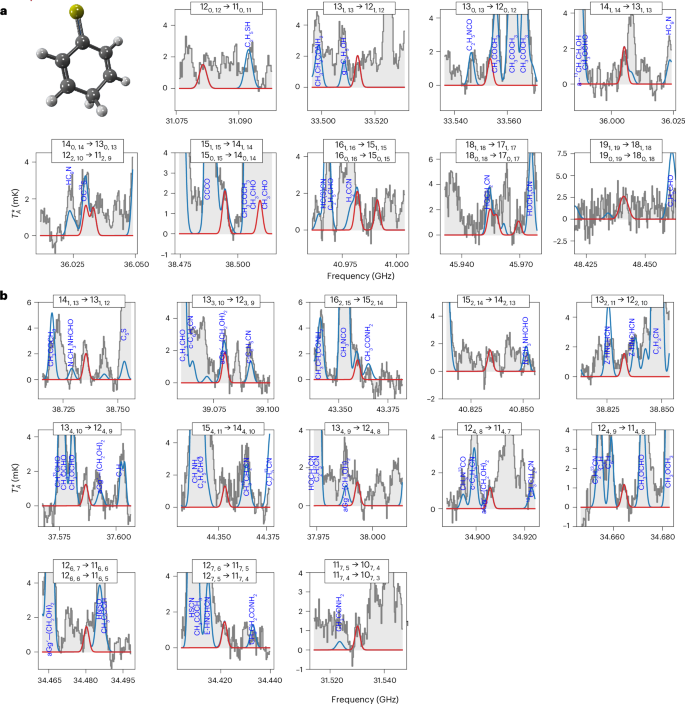

After assessing the emission of more than 140 molecules previously identified towards G+0.693, we detected many a-type transitions of 2,5-CT with an integrated signal-to-noise ratio >5 covering from the upper rotational levels Jup = 12 to 19, including several pairs of transitions belonging to two nearly complete progressions of (J + 1)0,J+1 ← J0,J and (J + 1)1,J+1 ← J1,J transitions (Fig. 1a), with the exception of the 121,12–111,11 transition, which lies out of the covered frequency range, and the 171,17–161,16 and 170,17–160,16 transitions, which seem to be heavily blended with unidentified lines. These pairs of lines progressively converge as the frequency increases, eventually coalescing into a doubly degenerate line for Jup = 19. Overall, we found 22 unblended or slightly blended features, the latter being contaminated by less than 25% (Fig. 1; spectroscopic information is listed in Extended Data Table 2, including an analysis of the contamination). These were subsequently used in the LTE fitting and to derive the physical parameters of 2,5-CT (detailed information about the LTE fitting using the MADCUBA-SLIM tool and the definition of an unblended line is provided in the Methods section). We stress that no missing lines were observed within the whole dataset, and the remaining lines were either heavily blended or too weak to be observed (transitions at 2 mm and 3 mm that did not rise above the noise). Our results are in agreement with the observed spectra.

a, Pairs of Ka = 0 and 1 transitions that progressively converge with increasing frequency, ultimately coalescing into a doubly degenerate line. b, Ka > 1 transitions of 2,5-CT observed in the astronomical data that were also used to derive the LTE physical parameters of the molecule (see text; listed in Extended Data Table 2). The quantum numbers for each transition are shown in the upper part of each panel. The red lines depict the result of the best LTE fit to the 2,5-CT rotational transitions. The blue lines are the emission from all the molecules identified to date in the survey, including 2,5-CT, overlaid with the observed spectra (grey histograms and light grey shaded area). The three-dimensional structure of 2,5-CT is also shown (carbon atoms in grey, S atom in yellow and hydrogen atoms in white).

The best-fitting LTE model for 2,5-CT (shown in red in Fig. 1) yields an excitation temperature Tex = 14.3 ± 3.4 K, a radial velocity vLSR = 71.7 ± 0.9 km s−1, a linewidth with a full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of 20.0 km s−1 and a molecular column density N = (5.6 ± 0.3) × 1012 cm−2, which translates into a fractional abundance with respect to H2 of (4.1 ± 0.7) × 10−11, using N(H2) = 1.35 × 1023 cm−2 as derived by ref. 45. A complementary population diagram analysis has also been performed46, which gave physical parameters that are in good agreement with the SLIM-AUTOFIT analysis: N = (5.6 ± 1.4) × 1012 cm−2 and Tex = 12.5 ± 1.5 K (Methods section and Extended Data Fig. 4). The partition functions used are listed in Extended Data Table 3.

Astrophysical implications

The detection of 2,5-CT opens a new window into the chemistry of large S-bearing cyclic molecules in the ISM, and it provides the first basis for elucidating their abundance and formation. The most straightforward comparison is between 2,5-CT and its structural isomers, 2,4-CT and thiophenol, which are not clearly detected in the current astronomical data (Methods section). Based on the derived upper limits for both molecules (N(2,4-CT) ≤ 3.2 × 1012 cm−2 and N(thiophenol) ≤ 8 × 1013 cm−2), we expect that 2,5-CT is more than twice as abundant as 2,4-CT (which is close to the factor of ~2 estimated in our laboratory from the relative intensities of rotational lines) whereas N(thiophenol)/N(2,5-CT) < 14. Of the two structural isomers, 2,4-CT and 2,5-CT, it would be expected from the energy level diagram (Extended Data Fig. 1) that the low-energy one would be more abundant, in agreement with the detection, but the relatively low dipole moment of thiophenol compared with those of both 2,5-CT and 2,4-CT (Extended Data Table 1) prevents us from unveiling conclusively whether only 2,5-CT is selectively produced in the ISM or whether 2,4-CT and thiophenol are also present but remain undetected due to sensitivity limitations. Besides the emergence of 2,5-CT as the only structural isomer identified to date for the C6H6S family, our findings now confirm the existence of large (more than ten atoms) sulfur-containing cyclic species in the ISM. Although 2,5-CT itself accounts for only a small fraction of the S budget detected towards G+0.693 so far (~0.05%; Sanz-Novo, private communication), its discovery may be just the tip of the iceberg of a yet unexplored chemistry. This scenario might closely mirror that of benzonitrile, whose initial detection in the ISM by McGuire et al.18 preceded the discovery of numerous cyano-substituted PAHs, and is in line with the rich inventory of S-bearing rings in meteorites, with over 80 species detected (including thiophenol, dibenzothiophene and thianthrene6,14. By analogy with the nearly flat abundance trend of cyano-bearing rings found in Taurus Molecular Cloud 120,22, the cumulative contribution of the C6H6S isomers in G+0.693 could approach ~1.5% of the total S reservoir, hinting that S-bearing cyclic hydrocarbons and S-bearing PAHs might not represent a relevant sink of sulfur in the ISM. In this context, if a small portion of sulfur is locked up in S-bearing PAHs and related S-containing cyclic species, we anticipate that the James Webb Space Telescope is capable of detecting several infrared features26, even though some of the prominent bands (for example, the 10-μm C–S-band) may be obscured by the 9.7-μm silicate absorption band. Moreover, upcoming radioastronomical facilities, such as the Square Kilometre Array or the Atacama Large-Aperture Submillimeter/millimeter Telescope, will probably find a rich reservoir of large cyclic S-bearing species, including potentially prebiotic molecules.

The detection of 2,5-CT can be rationalized in terms of its large dipole moment (a-type dipole moment μa = 4.73 D; Extended Data Table 1). This result establishes this organosulfur species as a promising observational link between the rich S inventory found in the minor bodies of the Solar System (asteroids, comets and meteorites), which includes a wide array of cyclic S-bearing compounds, ranging from thiophenol6 and thiophene15 to the more complex diphenyl disulfide, dibenzothiophene and thianthrene14, and the known S budget in the ISM, which has been limited so far to the detection of molecules with up to nine atoms10,11,12. With 13 atoms, 2,5-CT now ranks as the largest S-bearing molecule detected so far in the ISM, marking an important step forwards in molecular size and complexity within interstellar sulfur chemistry. Previously, the largest S-bearing interstellar species had up to nine atoms (for example, ethyl mercaptan, CH3CH2SH, and its isomer dimethyl sulfide, CH3SCH3 (refs. 10,12)). In this context, 2,5-CT is the largest S-bearing complex organic molecule detected so far and also the most complex S-bearing cyclic species. Thus, it provides a novel view on cyclic interstellar chemistry, which now extends beyond pure hydrocarbons and their cyano (–CN) and ethynyl (–CCH) derivatives. Additionally, our findings highlight the need for caution when analysing mass spectrometric measurements of cometary, meteoritic and asteroid material targeting thiophenol, as the mass peak could be contaminated by 2,5-CT, given that both molecules share the same molecular mass (110.02 u). Consequently, although 2,5-CT has not, to our knowledge, been searched for in extraterrestrial material from these minor bodies, it may still be present but unidentified.

To date, the potential formation routes for 2,5-CT and related S rings remain largely unexplored, both experimentally and theoretically. Consequently, we can only hypothesize its possible formation routes by either studying chemically related species or by drawing analogies with bottom-up pathways proposed for related cyclic species. Given the uncertain efficiency of gas-phase pathways, such as those invoked for benzene formation through ion–molecule reactions47, which are considered to be the bottleneck in the growth of larger PAHs, a potential dust-grain origin appears particularly promising in G+0.693. Laboratory simulations have shown that cosmic-ray irradiation of low-temperature acetylene (C2H2) ices efficiently produces benzene48, indicating that an analogous chemistry involving small S-bearing carbon chains (for example, C2S and C3S, and also the detection in the ISM of up to the five-carbon member, C5S; ref. 49) and C2H2 on icy grains could lead to 2,5-CT. Although this hypothesis still needs to be tested in the laboratory, it is supported by two key factors that shape the chemistry of G+0.693, where linear S chains are also abundant (for example, N(CCS) = 1.5 × 1014 cm−2): (1) Its elevated cosmic-ray ionization rate (10−14–10−15 s−1), estimated through chemical modelling involving cations such as PO+ and HOCS+ (ref. 37 and references therein), which favours radical formation and recombination on grain mantles34. (2) The occurrence of large-scale low-velocity shocks associated with a cloud–cloud collision scenario50, which enhance the sputtering of icy grain mantles and could facilitate the desorption of molecules such as 2,5-CT. An analogous connection has already been suggested between benzonitrile, which is also detected in G+0.693 (Rivilla, V. M., private communication), and the cyanopolyyne family51, but for 2,5-CT, the inclusion of ring defects (a (–CH2–) moiety that disrupts the electron delocalization and, thus, the aromaticity within the ring) needs to be addressed. Alternatively, benzene could be directly released from the grains through shocks and subsequently react through radical–neutral reactions52,53, which are considered to be some of the main formation routes for diverse PAHs, such as c-C6H5CN (ref. 18), c-C10H7CN (ref. 19), c-C5H5CN (ref. 30) and c-C16H9CN (refs. 20,21). However, apart from a recent study on the production of c-C3H2S via c-C3H2 + SH (ref. 27), there are no theoretical or experimental data that support an analogous formation route starting from c-C6H6 and yielding 2,5-CT or any of its isomers (for example, thiophenol).

In summary, the study of interstellar chemistry of large cyclic species (>12 atoms) has been bound so far to pure cyclic hydrocarbons or cyano (–CN) and ethynyl (–CCH) derivatives, as their derivatization provides a sizeable dipole moment to the parental, typically nonpolar hydrocarbon (for example, benzene, naphthalene or pyrene), thus enabling their radioastronomical identification. The interstellar detection of 2,5-CT presented here, which is based on new high-resolution rotational data, demonstrates that interstellar cyclic chemistry extends beyond the aforementioned families to encompass S-bearing compounds. These findings open the window to a yet uncharted S chemistry, which, although it might not account for the missing sulfur in dense interstellar environments, does contribute considerably to our understanding of the origin of sulfur-containing molecules in meteorites and comets and provides insight into sulfur reservoirs in young solar-type systems.