Steel exporters to the EU started paying for the CO2 emissions linked to their production from the beginning of 2026.

Keystone-SDA

In a major shake-up of green trade rules, the European Union began charging a carbon-emissions tax on imported goods such as steel and cement at the beginning of this year. Here’s how and why this first-of-its-kind policy, known as a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)External link, is already reshaping climate practices far beyond the EU.

Switzerland’s approach to the new tax has been cautious. The non-EU country is exempt from the CBAM but will reassess its position on this type of carbon tax scheme this year. Developing countries meanwhile have warned that the EU’s scheme is unfair. And while the CBAM is already having an effect, its long-term success will depend on whether it pushes other countries to adopt their own schemes for pricing carbon.

What is the EU’s carbon border levy and how does it work?

Initially, the tax applies to cement, iron, steel, aluminium, electricity and hydrogen that come into the EU at certain amounts. Reuters has reported that the EU plans to expand the tax to car parts, refrigerators and washing machines from January 1, 2028.

Instead of paying a tax directly, importers of these goods must buy CBAM certificates, which reflect the emissions embedded in their products. Under the CBAM system, a German carmaker importing steel from a non-EU country without carbon pricing, such as Turkey, must calculate the emissions embedded in the steel and the shipment, and buy the corresponding number of CBAM certificates. If the exporting country already prices carbon, the EU charges only the difference.

The CBAM builds on the EU’s existing carbon pricing system. Since 2005, heavy emitters inside the bloc have been required to pay for their emissions under the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS).External link CBAM certificate prices are linked to the EU ETS carbon price.

+ Switzerland and EU link carbon emissions trading systems

The phasing in of the new levy coincides with the phasing out of free carbon allowances that have been offered to polluting sectors covered by the EU ETS deemed at risk of “carbon leakage” – the relocation of emissions-heavy production abroad to avoid the region’s strict climate policies – and to help the sectors transition to carbon pricing.

Why has the EU introduced this CO2 levy?

CBAM is part of the EU’s Green DealExternal link, policy initiatives launched in 2019 to make Europe climate neutral by 2050.

The EU says the adjustment mechanism will help cut emissions and protect carbon-intensive EU industries from unfair competition with producers in countries with weaker climate rules. It is also meant to discourage “carbon leakage”.

The bloc also argues that CBAM encourages greener practices globally, as countries can avoid paying the levy by imposing an equivalent carbon price on domestic production.

What will be the impact of this levy?

Supporters say CBAM represents a major shift in global trade by embedding climate policy into trade rules and encouraging firms to decarbonise.

Catherine Wolfram, professor of energy economics at the MIT Sloan School of Management, calls itExternal link the most optimistic” development she has seen in 20 years of studying climate policy.

The policy appears to be influencing governments worldwide. Aurora D’Aprile of the Swiss-based International Emissions Trading Association told the AFP news agency there had been a “clear step change” in reaction over the past year, with countries including China expanding carbon pricing and others, such as Turkey, launching long-delayed emissions trading schemes.

Japan has explicitly cited CBAM in advancing its policies, while the UK plans its own mechanism from 2027. Australia, Canada and Taiwan are also considering or extending carbon pricing.

The EU’s own assessment projects that the CBAM would result in a 13.8% reductionExternal link in the bloc’s emissions by 2030, compared with 1990 levels, and a cut of about 0.3% for the rest of the world.

What is Switzerland’s position on the levy?

Swiss goods are currently exempt from CBAM because Switzerland’s emissions trading system has been linked to the EU since 2020. This means that companies effectively pay a comparable carbon price, with the linkage allowing mutual recognition of emission allowances and equal treatment under both systems. Switzerland is not required to introduce the CBAM under a bilateral ETS agreement.

In 2023, the Swiss authorities advisedExternal link against introducing an EU-style adjustment mechanism for imported goods, citing costs and regulatory and commercial risks. The CBAM “would also only benefit a small number of carbon-intensive industrial facilities in Switzerland, while generating disadvantages for the rest of the economy,” the federal government said.

But the issue continues to occupy lawmakersExternal link. In October 2025, a parliamentary committee adopted an initiative to create a Swiss border adjustment mechanism for cement-related importsExternal link. A consultation on draft legislation runs until February 20, 2026. Federal authorities also plan to re-assess by mid-2026 whether to introduce a broader Swiss CBAM, following an interim evaluation of the EU scheme.

Separately, Switzerland has a federal CO₂ levy, essentially a national carbon tax on fossil fuels like heating oil and natural gas, set at CHF120 per tonne of CO₂, which incentivises reducing fossil fuel use. Most revenue is redistributed to citizens and businesses, and a portion funds building efficiency and renewables. It also has carbon pricing on vehicle imports and an Emissions Trading System (ETS) for large emitters, aiming to meet its net-zero goals.

Which countries oppose the EU levy?

Countries most affected by the tax argue it will raise costs, restrict trade and slow economic growth.

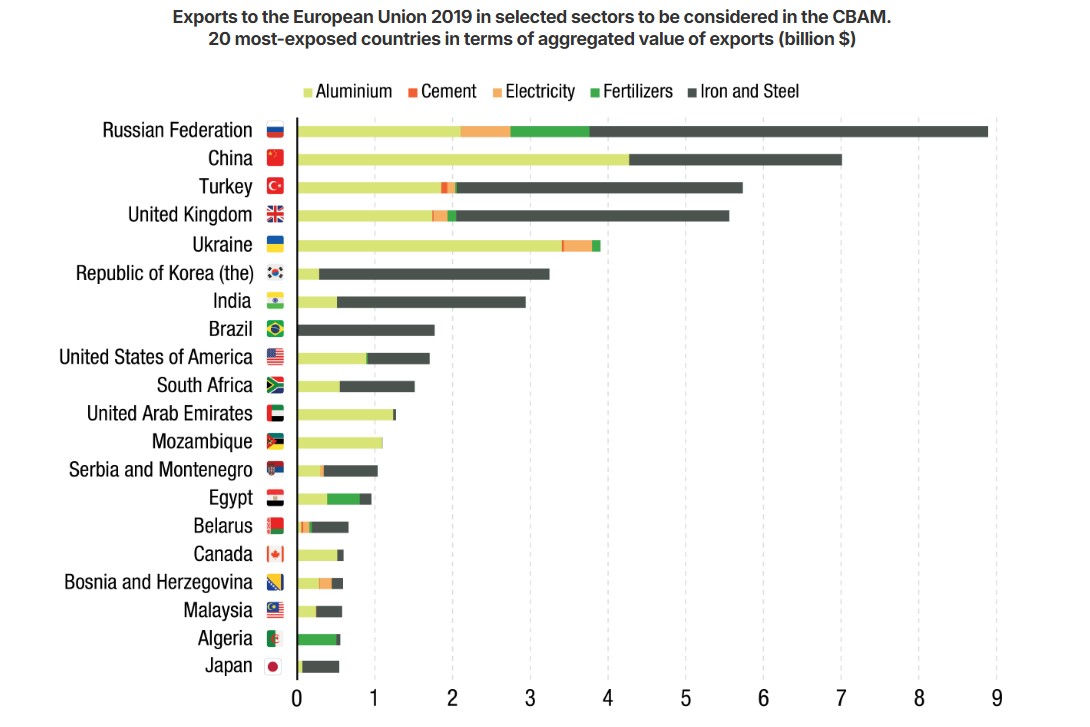

graph

UNCTAD based on UN COMTRADE.

Despite expanding carbon pricing, China’s commerce ministry has described the levy as “unfair” and “discriminatory”, warning it could undermine trust and raise the cost of climate action for developing countries. It has vowed to take countermeasures, and the issue was raised for the first time at the COP30 climate meeting in Brazil last November following pressure from a group of nations.

India, Russia and Brazil have also strongly opposed CBAM, calling it a unilateral trade measure disguised as environmental policy.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) says the EU must carefully consider the trade impacts of the CBAM. It says the mechanism could help avoid carbon leakage, but its impact on climate change would be limited – only a 0.1% drop in global CO2 emissions – with higher trade costs for developing countries. With a CBAM based on a carbon price of $44 per tonne, for example, the income of developed countries would rise by $2.5 billion, while that of developing nations would fall by $5.9 billion, according UNCTAD’s analysisExternal link published last July.

Georg Zachmann, a climate policy specialist at the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel views the CBAM as a “political success for the EU” and says its long-term impact will depend on whether other countries respond by introducing effective carbon pricing or similar mechanisms.

Why is there no universal carbon pricing system?

In an ideal world, all countries would price carbon emissions, says Philippe Thalmann, professor of environmental economics at the Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL). In reality, many governments resist such measures out of concern for economic growth.

“This European policy of punishing them in a certain way, or at least restoring a level playing field when they export their goods to the EU, is a softer answer than forcing them to have a carbon price on all their production,” he told Swissinfo.

Thalmann nonetheless believes CBAM is the right tool. “All steel production should be subject to carbon pricing around the world. And the CBAM system is a way of extending the European price to other countries. I think Switzerland should participate in this effort,” he said.

More

More

Emissions reduction

Why Switzerland’s carbon footprint is bigger than you think

This content was published on

Jan 23, 2025

Per capita CO2 emissions in Switzerland are lower than the world average. But the picture changes radically when you consider the emissions related to products imported from abroad.

Read more: Why Switzerland’s carbon footprint is bigger than you think

Edited by Gabe Bullard/vdv

Articles in this story