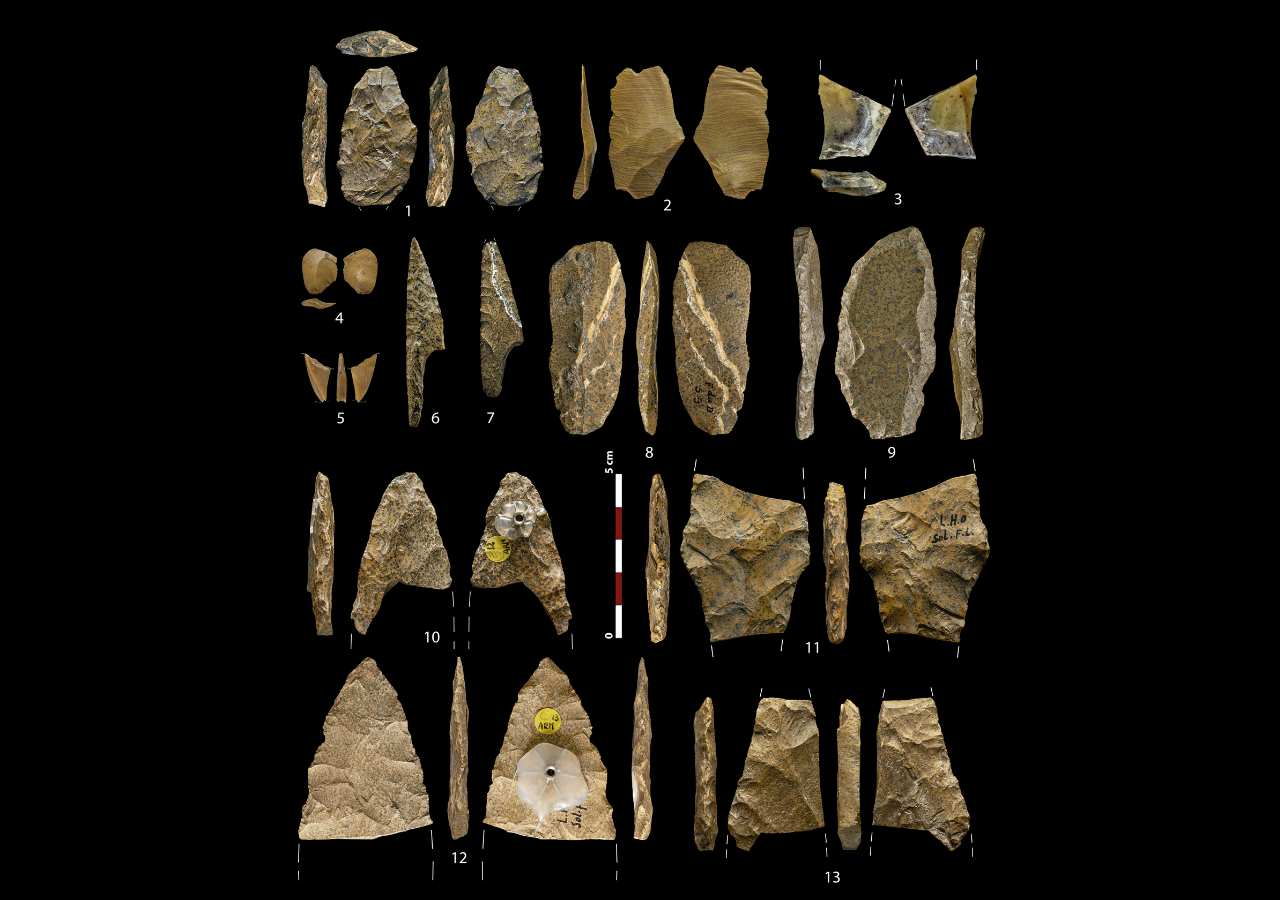

Solutrean tools from Peña Capón classified as lithotype 5. Credit: Marta Sánchez de la Torre / CC BY 4.0

Hunter-gatherer networks during the last Ice Age stretched far wider than many archaeologists once thought, linking groups in central Spain with communities in what is now southwestern France across distances of 600 to 700 kilometres (370 to 435 miles), researchers report.

The evidence comes from stone tools left in a rock shelter called Peña Capón, in the Upper Tagus River basin of Spain. A new study led by Marta Sánchez de la Torre, published in Science Advances, traced the geological “fingerprints” of the stone. Some of it did not come from nearby river valleys or Spanish plateaus. It matched sources north of the Pyrenees.

That is a big surprise because most proven movements of stone raw material in Paleolithic Europe fall within local and regional ranges. Long jumps are rare. The team says this is the longest confirmed source-to-site distance for a knapped stone object reported so far for Europe’s Upper Paleolithic.

A long-occupied site holds clues to ancient movement

Peña Capón holds a long sequence of Ice Age occupations dated to roughly 26,200 to 22,200 years ago. These layers include the Solutrean tradition, known for finely made stone points. The new work focuses on what the tools were made of, and what that can reveal about how people connected across harsh, glacial landscapes.

To track the stone, researchers studied more than 1,000 artifacts from the site. They first sorted the materials by texture and microscopic traits. Then they used chemical testing—laser-ablation mass spectrometry—to measure elements inside selected pieces and compare them with hundreds of geological samples collected from Spain and France.

Most stone was local, but some traveled astonishing distances

Most of the stone fits a practical pattern. It came from regional sources that people could reach in short trips. Some came from farther basins, including areas that would have taken many days of travel to reach directly. But a tiny set stood out.

A handful of artifacts matched a specific jasper-like stone found in Lower Jurassic formations on the western edge of France’s Central Massif. The match was not based on looks alone. The chemical data separated French sources from Spanish ones and placed several Peña Capón samples inside the French “cluster,” the researchers said.

Exchange networks offer the clearest explanation

The travel distance is so large that the team argues the Peña Capón occupants almost certainly did not walk to France just to get better stone. In fact, the French material does not appear to be the best option for toolmaking compared with the closer stones available in Iberia.

A new study shows hunter-gatherer networks linked central Spain and southwest France over distances of 600+ km, using stone tools to maintain social ties during extreme cold. pic.twitter.com/J7844qagYi

— Tom Marvolo Riddle (@tom_riddle2025) January 23, 2026

Instead, the researchers point to exchange. They say the simplest explanation is “down-the-line” movement, where materials pass through several groups, step by step, across a wide region. In this view, the stone moved through social ties—visits, alliances, marriages, shared seasonal gatherings, or reciprocal gifts—rather than through one long supply run.

Modeling shows journeys beyond known hunter-gatherer ranges

Computer modeling adds weight to that argument. When the team ran least-cost travel estimates across real terrain, the route from Peña Capón to some French outcrops implied a return journey measured in weeks, not days. One estimate reached about 35.6 days for a round trip on foot.

Such distances exceed the annual movement ranges documented for any known hunter-gatherer group, including highly mobile Arctic populations. The scale, researchers say, only makes sense if many groups participated in a linked network.

A symbolic object may mark a social connection

One object helps explain why this stone mattered. In a Middle Solutrean layer, the team identified a leaf-shaped point “preform,” an unfinished piece shaped like a laurel leaf. Use-wear analysis suggested it was transported after shaping and was never used as a weapon or cutting tool.

That finding supports the idea that the object carried meaning beyond simple utility. The researchers suggest such items may have functioned as social signals or gifts that helped reinforce long-distance relationships.

Networks helped people survive a harsh climate

The study suggests these ties lasted, not just happened once. Based on where the French material appears within the layers, the researchers say the long-range network operated for about 1,400 years during a brutally cold stretch of the Last Glacial Maximum.

The team frames these connections as a “safety net.” During periods of extreme cold and resource uncertainty, wide social networks could reduce risk by sharing information, maintaining alliances, and preserving cultural knowledge.

The findings also challenge the idea that inland Iberia was isolated during the Ice Age. Peña Capón, the researchers conclude, sat within a connected world—one where people, ideas, and even stone tools moved across mountains and across much of western Europe.