When you’ve only lived for a decade, the next one stretches ahead of you like an apparent eternity. To the elders raising you, it goes by in the blink of an eye. Docmakers Itab Azzam and Jack MacInnes maintain both those perspectives in their film “One in a Million,” charting changes at once vast and disorientingly swift in the life of a young Syrian refugee estranged from her past and unsure of her future — and in the present, growing up faster than her similarly unmoored parents can process. First encountering their 11-year-old protagonist Israa in 2015, when she and her family have been newly displaced from their home in Aleppo, Azzam and MacInnes spend ten full years following her through several stages of cultural alienation and adaptation, alongside the more universal trials of adolesecence.

The resulting film is both a stirring addition to the veritable library of documentaries on the European migrant crisis that has built up in the last ten years, and an unusual, high-stakes example of a time-lapse coming-of-age study — that fascinating subgenre that covers the likes of Michael Apted’s “7 Up” series in nonfiction and Richard Linklater’s “Boyhood” in narrative cinema — as its young human subject steadily and turbulently grows up before our eyes. Despite the jagged circumstances under scrutiny, this is a highly polished, emotionally accessible production, sure to connect with substantial TV audiences when it airs on PBS’ Frontline and the BBC’s Storyville strands following its Sundance competition premiere.

“One in a Million” opens near the end of Israa’s journey, as the 21-year-old returns in 2025 to Syria following the fall of the Assad regime, gaping in astonishment at the bombed-out skeleton streetscapes of Aleppo — a place of which she only has sheltered childhood memories, further burnished by ten years of absence. It’s a cathartic return, though it’s ambiguous whether it’s a homecoming or not: After years of living as a refugee in Europe, Israa finds it’s possible to feel like a foreigner on one’s native soil. We rewind to the filmmakers’ first encounter with Israa and her family, on the sidewalks of Izmir, Turkey in 2015, shortly after their initial flight from Syria. Selling cigarettes on the street to buy food for her siblings, the pre-teen is indefatigably upbeat, eagerly anticipating an imminent passage to Germany.

Her middle-aged father Tarek, meanwhile, is rather more circumspect. “I’m gambling with the lives of my children,” he admits to the filmmakers, who appear to gain the family’s full trust and candor early on in proceedings — to the point that Israa, on seeing her parents fighting, immediately reports to the camera crew in the hope of breaking up the conflict. There’s more tension than initially meets the eye in the marriage between Tarek and Israa’s mother Nisreen, a camera-shy presence in the first years of filming, who feels significantly more empowered to speak for herself as she settles into a European way of life.

Upon their arrival in Germany, these family dynamics further shift and sour: Nisreen and Israa soon embrace the independence that women are afforded in their new environment, while Tarek retreats into a mindset of resentfully conservative patriarchy. As anyone who has raised a teenager might expect, however, Israa’s arc of change isn’t a smooth curve, as she pivots between brazenly westernized rebellion and a more demure embrace of her Islamic roots — particularly when an older boyfriend, fellow Syrian refugee Mohammed, enters the scene.

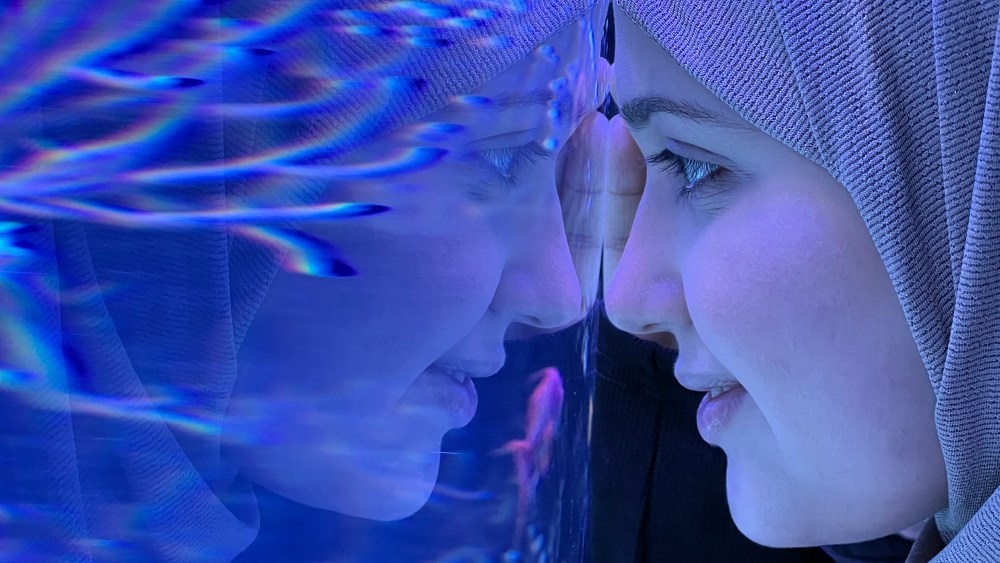

As she approaches adulthood, Israa assertively distances herself from Tarek, revealing him to be a volatile abuser, but more passively drifts from the influence of her liberated mother, who’s loath to romanticize any aspect of her Syrian past. Nisreen understands her daughter’s homesickness but refuses to share in it. “She didn’t go through what I went through,” she says curtly, in one of the film’s later talking-head interviews — all of which are exactingly shot, lit and styled to mark the participants’ changing appearances and outlooks. (The Nisreen we see at the film’s close, perfectly made up in a turquoise hijab that sets off her pale blue contact lenses, is a pointedly different presence from the modest, retiring figure she cuts at the outset.)

Azzam and MacInnes, a married couple from Syria and the U.K. respectively, are well-placed to address these intricate cultural confrontations with tact and empathy, though they maintain a largely observational stance over the course of filming — “One in a Million” is one of those close-quarters character-study docs filmed with such intimate fluidity that you almost forget the complexities of inserting a camera in this fraught domestic space. (Simon Russell’s lushly emotive score gives some scenes the heightened sweep of teary fiction.)

Early on in proceedings, Israa embraces the gaze of the lens, wondering if fame awaits her; by 21, with her life still at a crossroads, she seems ready to figure it out in private. In following her to this point, however, this long-game project gives remarkable dimension and particularity to the kind of migrant story often only told in journalistic generalities — showing, year on year, how time heals some wounds, opens others, and creates plenty of its own.