3D render of waste from broken artificial satellites floating in orbit in space around planet Earth. (credit: West Virginia University)

Thousands of existing seismic stations worldwide can now help locate falling satellites before hazardous materials spread

Earthquake sensors can track falling space debris through atmospheric reentry when radar and optical systems fail

A Chinese spacecraft that fell over California in 2024 landed 5,400 miles from predicted location; seismometers caught the real trajectory

The technique captured the spacecraft breaking apart piece by piece in a two-second cascade, revealing how debris actually fails

When a 1.5-ton Chinese spacecraft came screaming back to Earth over Southern California last April, something unexpected happened. While radar lost track and satellites couldn’t see through the fiery plasma, a network of earthquake sensors on the ground captured the whole thing, sonic boom by sonic boom.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University and Imperial College London discovered they could use seismometers to track falling space debris through the most dangerous part of reentry, when everything else goes blind. Their analysis of the Shenzhou-15 orbital module’s breakup, published in Science, revealed where it traveled and where it broke apart in real time.

The timing couldn’t be better. Spacecraft are falling from the sky at an exponential rate. Every week brings another fireball streaking across someone’s neighborhood, and we’re usually terrible at predicting where the debris will land.

Take the Shenzhou-15 case. Official predictions said it would crash into the Atlantic Ocean at 9:06 AM. Instead, it broke apart over Southern California 25 minutes earlier and nearly 5,400 miles away from the predicted location. Residents across the greater Los Angeles area saw a bright fireball fragmenting overhead at 1:40 in the morning, trailing pieces across the desert.

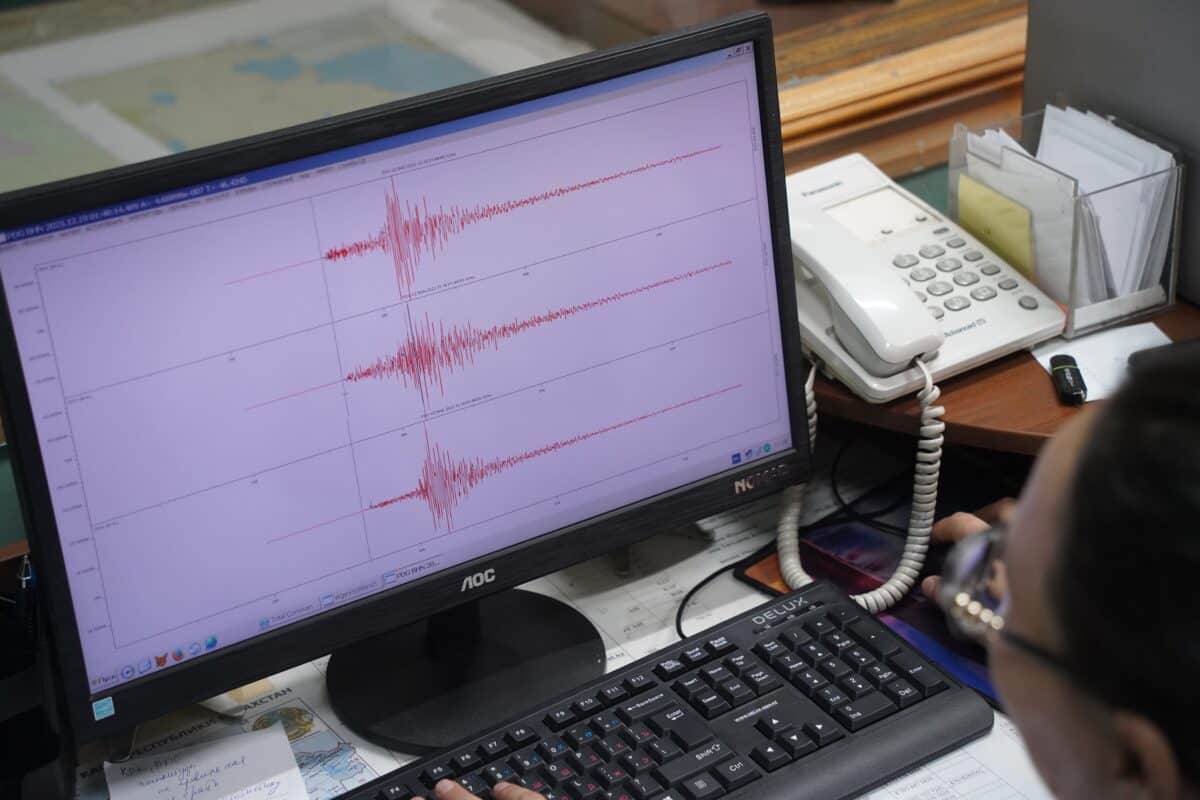

Seismometers designed to detect earthquakes can now track falling space debris through atmospheric reentry, revealing how spacecraft break apart in real time. (Credit: Vladimir Tretyakov on Shutterstock)

The Sonic Boom Solution

Why does this new technique work? When something moves faster than sound, it creates a shock wave. A spacecraft reentering at 25 times the speed of sound produces a massive one. That shock wave hits the ground as a sonic boom, and earthquake sensors are exquisitely tuned to detect exactly that kind of pressure wave.

The Shenzhou-15 module created sonic booms that registered at 125 seismic stations across California and Nevada. Each station recorded when the boom arrived, and those arrival times told a story.

The earliest station to pick it up was on San Miguel Island in the Channel Islands. The sensor there captured a sharp pulse — ground compression followed by rebound — lasting just 0.15 seconds. That’s important because an intact spacecraft at that altitude and speed should produce a pulse lasting closer to half a second. The abbreviated signal meant it wasn’t one intact hulk anymore, but likely a tight cluster of smaller pieces.

As the debris traveled inland, stations recorded increasingly complex patterns. Multiple sonic booms arrived in rapid clusters, each one representing a piece of spacecraft tearing away from the main body. The pattern revealed something engineers had suspected but never directly observed: spacecraft don’t explode catastrophically or simply burn away. They fail like a zipper coming undone. One piece breaks off, which causes more stress on the remaining structure, which breaks off more pieces, and so on.

Researchers isolated 8 to 11 distinct breakup events happening within two seconds. Parent fragments split into smaller pieces, which split again, each separation creating its own shock wave. The whole cascade played out across roughly 10 miles of sky.

Filling the Tracking Gap

The seismic method solves a problem that’s been plaguing space agencies for decades. Current tracking works fine when spacecraft are high up in stable orbits. But once debris drops into the atmosphere and starts burning up between 50 and 95 miles altitude, the tools we rely on stop working.

Radar gets confused by the superheated plasma surrounding the debris. Optical telescopes lose line of sight. By the time anyone figures out what happened, pieces might already be on the ground, potentially contaminating soil with toxic propellants, scattering radioactive materials from power systems, or just putting chunks of metal through someone’s roof.

Earthquake sensors don’t care about plasma or line of sight. They just detect pressure waves hitting the ground, and there are thousands of them already installed across the United States and around the world. No new infrastructure needed. The method won’t tell response teams exactly where a chunk landed, but it shrinks the search area fast.

The technique works even in areas with sparse coverage. California’s dense seismic network made the Shenzhou-15 analysis particularly detailed, but researchers showed they could get useful results with far fewer sensors. That matters for tracking debris over oceans or remote regions where we don’t have much radar coverage.

The Growing Space Debris Problem

Space is getting crowded fast. SpaceX’s Starlink constellation alone has launched thousands of satellites in the past few years. Every single one will eventually come back down. Most will be controlled reentries that burn up harmlessly over the ocean. But not all.

Satellites malfunction. They run out of fuel. Sometimes operators just abandon them in decaying orbits. Once a satellite starts tumbling, predicting where it’ll land becomes a guessing game.

Some components are built to survive reentry. Titanium fuel tanks, for instance. The structural frame on larger satellites. These don’t always burn up completely, and they can travel a long way during the final descent.

The old approach was essentially: watch it fall, try to predict impact zones, then scramble response teams once debris is found. That works poorly when predictions are off by thousands of miles.

Seismic tracking offers something different: a continuous record of where the spacecraft broke up and how the pieces dispersed. Where the breakup happened, how fast debris was traveling, what altitude the pieces reached before the sonic booms stopped. Response teams can use that information to narrow their search immediately, rather than combing blind across vast areas.

What Comes Next

The technique opens doors beyond just tracking debris. The data reveals how spacecraft actually fail under the intense forces of reentry. That two-second cascade told engineers that atmospheric pressure of just 1 to 2 kilopascals (about 0.3 pounds per square inch) is enough to start tearing apart a module traveling at these speeds.

That’s useful information if you’re designing satellites meant to completely disintegrate on reentry, or if you’re building capsules that need to survive it.

More immediately, it means we have a tool that works right now with existing infrastructure. The next time someone spots a fireball overhead and wonders “should I be worried?” — we’ll have better answers faster.

Limitations

The study acknowledges several constraints in the seismic inversion method. Altitude estimation from relative arrival times proved challenging because changes in source elevation produce only minor effects on wavefront incidence angles, particularly near the trajectory line. Distant stations show stronger altitude signals, but these measurements are complicated by atmospheric refraction, multipathing, and air-to-ground coupling effects. The researchers’ altitude estimate of 80 to 150 kilometers carries substantial uncertainty for this reason. The method also assumes wavefront coherence over distances of several kilometers—an assumption that becomes less valid for smaller fragments or at greater distances from the trajectory. Additionally, the technique cannot directly detect ground impacts; it only indicates where sonic boom generation ceased.

Funding and Disclosures

Benjamin Fernando is funded by the Blaustein Fellowship at Johns Hopkins University. Constantinos Charalambous receives support from the UK Space Agency Fellowship in Mars Exploration Science under grant ST/Y005600/1. The authors declare no competing interests.

Paper Citation

Fernando, B., & Charalambous, C. (2026). “Reentry and disintegration dynamics of space debris tracked using seismic data,” published in Science, January 22, 2026, 412-416. DOI: 10.1126/science.adz4676. Authors are affiliated with the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Johns Hopkins University (Fernando) and the Department of Electronic and Electrical Engineering at Imperial College London (Charalambous).