Meteorologists frequently mention weather prediction models in their forecasts. They explain what they’re gleaning from the “U.S. Model,” for instance, and how that might differ from the “European model.”

WRAL meteorologists Elizabeth Gardner and Grant Skinner broke down the ingredients of the models, explaining why the models sometimes contradict one another, and how they use the models — as well as their own experience and expertise — to refine their forecasts.

Q: From a high level, what are weather models? What are the data ingredients that go into them?

Gardner: County observation sites are collecting the temperature, wind speed, humidity, all of that multiple times a day on regular intervals. We have 100 counties in North Carolina and 50 states across the country. So then multiply that by the entire world — there is an incredible amount of surface data.

Skinner: And then there’s upper-air data, which is taken primarily through weather balloons. They take a vertical profile of the entire atmosphere, starting from the surface all the way up. Having that data is integral for understanding a full scope of what the weather system looks like and what it might look like in the future, with other ingredients in mind.

Gardner: All that data goes through a physics equation that describes the atmosphere, and then a computer says, “Oh, if this is what’s happening now, here’s what will happen tomorrow and the next day, and the next day, the next day.” So the farther we get out from today, the less accurate that’s going to be. That’s why we can’t give you a forecast three months out.

Q: Do these models learn over time, adding data along the way to help improve predictions?

Skinner: Climatology, the study of long-term atmospheric trends, plays a huge part in determining what will happen in the future. Of course, your initial data is super-important as well, and having great initial data like observations at the surface and the upper-air data is very important. But climatology also plays a big part in determining what will happen in 24 to 36 hours, based on prior events.

Q: What role is artificial intelligence playing in forecasting?

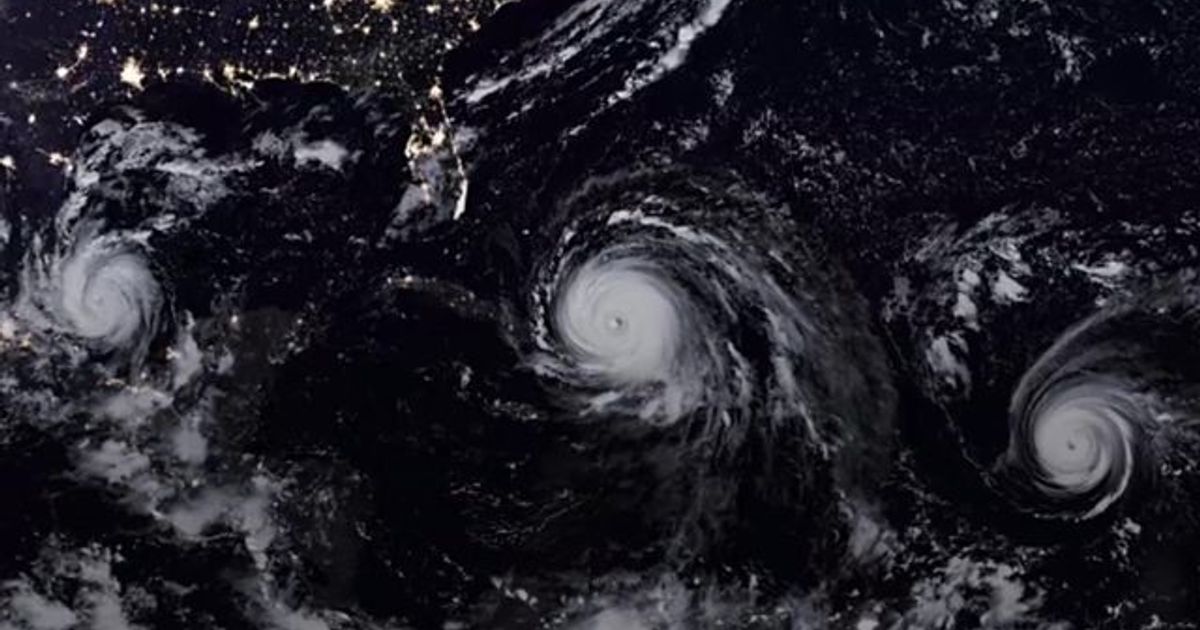

Gardner: The National Hurricane Center has about a dozen hurricane models, and in 2025 it added AI to to see how it would do. And it did outperform other models, not by a huge amount, but some amount. That’s something that we’ll probably see more and more of. It’s not changing the way forecasting is happening. It’s just enhancing it. So the model is analyzing what’s going on. And if you add AI to it, it can do it more completely.

Q: We hear references to the “U.S. model” and the “European model” all the time. What are the differences, and why are their forecasts sometimes contradictory?

Skinner: The U.S. model is the global forecasting system and is run by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction. It uses a combination of surface and upper-air data, information from satellites, climatology, and other data to make weather predictions out to 16 days.

Gardner: And then the European model is basically the same thing, but paid for and run in Europe. These are mostly run by governments because it’s so expensive to collect the data. And the data is public domain because it’s mostly taxpayer money that funds these things. The European model had been funded a lot more heavily. And the American model has caught up a little bit. But because of the quality and the amount of data going into the European model, sometimes it tends to be a little more accurate.

Q: So is that the reason why they sometimes differ — because the European model has more data?

Gardner: Yes, the more data that goes into it, the more accurate it’s going to be. There’s just more data going into the European model. The formulas going into it may be slightly different as well; there are a lot of ways you can subtly alter a model to give you a bigger range of what is happening out there.

Q: There’s obviously a lot of math and science in meteorology. It sounds like there’s a little bit of art, too, when you apply your expertise to the models to come up with your forecast, right?

Skinner: There are little nuances with forecast models, and so we assess those things. I watch for trends over a long period of time. Now that I’ve been here for a little while, I have a better understanding of what different adjustments I need to make based on the model output, and then I can use that to make my best judgment on what the temperature might be tomorrow morning, what the temperature is going to be in the afternoon, and to determine whether we’ll have severe weather in a couple of days.

All the data we get from forecast models, coupled with information that we know about the area, play a huge part in knowing what will come in the future. And it takes that human knowledge of the area and the geography. For example, with Chantal in July of 2025, we were able to give advance notice about the possibility for isolated tornadoes and flash flooding given the path of the storm and our knowledge of tropical systems. It ended up bringing multiple tornadoes and significant flooding in a large stretch of our area.

Q: What other data do you consider as you come up with your forecasts?

Skinner: In addition to forecast models, I’m also looking at climatology, which is basically looking back at data from previous years — what’s our record-high temperature, our record-low temperature, our normal temperature for that specific day. That can give you a general idea of where we should be. So if a forecast model, for example, is pointing to a record high but the pattern doesn’t support that, you would generally know that this forecast model is not doing well and you can probably scratch that data, or maybe not weigh that as heavily as other forecasts you’re considering. And sometimes, even though climatology goes into that forecast model, it can still be way off. But climatology can give you a starting point — we should be generally around this temperature, but we can also have extremes.

Q: I’m sure you encounter people who rely solely on the stock weather app that comes with their smartphone. Is that a good gauge?

Skinner: In general? No. Maybe for the average temperature for that day. But the stock weather app on your phone is not going to be very helpful because it is purely looking at raw data output, and it just has a hard time being able to bring in things like climatology or the geography for your specific area. During a cold-air damming pattern, we generally know that temperatures will usually trend below average or below what forecast guidance is showing, because usually we have a shield of cloud cover in place and just it stays colder. I’ve seen that with every cold-air damming event we’ve had here. Models have a hard time understanding that. Generally, it’s that human input that you need to be accurate day to day.

Q: Does the WRAL weather app provide that level of analysis?

Skinner: It does. And that’s because we are making updates throughout the day. When I come in for a morning shift, I update the forecast and then I’m updating it throughout the shift. When the evening meteorologists come in, they make their adjustments to the forecast. And we update our seven-day forecast every single day. We look at the newest model data, plus climatology, plus our own input. And on top of that, we have text and graphics that we update as well. You don’t get that with a stock weather app. Those graphics are tailored to our specific area because we know the area best.

Gardner: The WRAL weather app is going to be so much more accurate. It’s not just the computer model. You get the benefit of our expertise of having lived here for a long time and having studied meteorology. That’s what goes into our weather app, not just a single model. So it’s always going to be more accurate. I had a friend text me a little while ago, and she said, “Oh my gosh, is this really going to happen? I saw it on my weather app.” I’m like, “No, it isn’t. Would you please download the WRAL weather app?”

Q: You’re in the unenviable position of potentially being wrong on the weather — something for which people expect near certainty — because of things that you can’t control, such as last-minute changes in the atmosphere. How do you set expectations for viewers?

Skinner: If guidance is showing us that we have the possibility of having something serious, we put out that messaging. Even if we end up being wrong and something doesn’t happen, we want to make sure that we are preparing folks ahead of time — even if the ingredients don’t ultimately come together. I think part of the job is accepting that you are going to be wrong sometimes, but that doesn’t mean you don’t know how to do the job.

It’s just that it’s impossible to get it exactly right. There are times when we do hit it right in the mark — there are some days when we’re spot on with the temperature, with the timing of rain. And there are other days where it’s not so much. I’ve learned to not beat yourself up over that. You take it as a learning point and say, “Okay, why did that happen? How did it compare to model data? How did it compare to climatology?” All those things. I want to make the adjustment, so hopefully that improves in the future. And I understand that the viewer expects the correct forecast. That’s totally understandable. And generally we do a very good job of that.

Q: As predictive analytics improve, how will meteorology and forecasting change?

Gardner: I think we’ll probably see AI being added to more models. And that’s not a bad thing. A model is basically a computer helping to analyze the data. AI is sort of a ramped-up version of that. It only makes it better. Another thing that would make our models better is more data going into them. I don’t know that there’s anything coming right around the corner to help that, but that would really increase their accuracy as well.

Skinner: I think there will always be an element of human input to help sift through the model data. Unless you have a forecast model that is built specifically for your area, there’s going to be some — especially for global models — with errors and biases. Better data will make our job going into the process of forecasting a lot easier, because we understand that the model is doing a better job of understanding things. But I will say this — even with the forecast models learning over time and AI being incorporated, even high-resolution forecast models to this day still have their errors, and there have been times when they’ve been way off. So it’s always gonna take human input.

Q: People are generally more aware of predictive analytics and where to find data. Do you hear from arm-chair meteorologists who share their own analyses and interpretations of the models?

Gardner: I have a kid in my neighborhood who, from the age of 8, knew that he wanted to be a meteorologist, and he was able to teach himself how to read the models. The models are public domain because it’s all run by governments. So it’s out there. And especially with the advent of social media, people can just post it. And we love for people to be interested in weather.

The other side of that is that the models are not very accurate seven to 10 days ahead of a weather event, so I think people get confused and they may feel like the weather forecast is wrong, but they don’t realize that. Before we had social media, we would wait until three or four days out to give people enough time to prepare for a storm, but also to give them more accurate information. We still do that, but we can’t stop the public from seeing all this crazy information that can come from the models.

Q: Are there viewers who have offered insight into the weather that you hadn’t thought that turned out to help you with your forecasts?

Skinner: I’ve had some folks that give me insight into past severe weather events. That’s super helpful, to have a better grasp on how the community was affected by it. They’ll also tell us “the forecast was showing this, but then it changed, this close to the event” and other details leading up to an event that I may not have seen before. It helps me to understand the climatology part a little bit better.