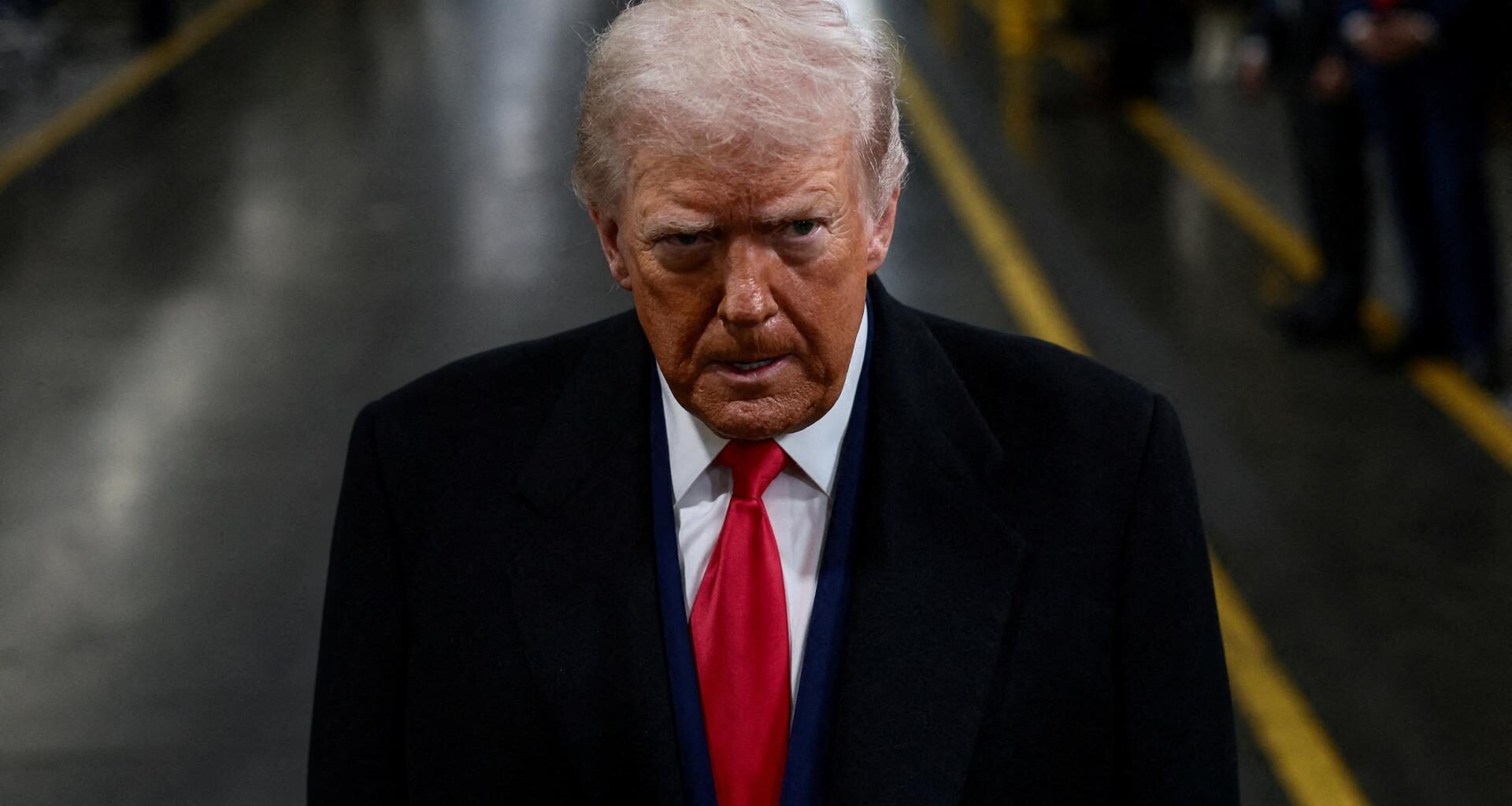

U.S. President Donald Trump visits a Ford production center in Dearborn, Michigan, U.S., Jan 13. Reuters-Yonhap

U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to hike tariffs on Korean imports has reignited a fierce debate over the fragility of international pacts and whether Seoul has failed to honor a bilateral trade agreement with Washington. At the heart of the friction is a fundamental disagreement over whether a pending bill in Seoul constitutes a broken promise in Washington.

Trump said Monday (local time) that tariffs on a wide range of Korean goods, including automobiles, timber and pharmaceuticals, would be raised from 15 percent to 25 percent, arguing that Korea’s National Assembly had not approved the agreement reached between the two countries.

Korean officials have scrambled to push back, arguing that the agreement is already in motion. They point to a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that allows for tariff cuts to take effect retroactively, dating back to the first of the month in which implementing legislation is merely introduced.

After the ruling Democratic Party of Korea submitted the bill on Nov. 26, 2025, the U.S. initially honored this clause, applying cuts back to early November. From Seoul’s perspective, the “act of submitting the bill” was the finish line. For the Trump administration, it appears to have been only the starting block.

At the center of the dispute is the status of the so-called Special Act on Strategic Investment in the United States, which remains pending at the Assembly.

The bill has been introduced but has not yet cleared the committee with jurisdiction, leaving it short of final passage. Trump has pointed to the unfinished legislative process as grounds for questioning Korea’s compliance with the agreement.

The government and the ruling party argue that a delay in legislative procedures does not amount to a breach of the agreement. They note that the deal was concluded as an MOU rather than a treaty and does not explicitly require parliamentary ratification or specify a deadline for the passage of implementing legislation.

From Seoul’s perspective, the condition for tariff reductions — submission of the bill — has already been met, and the agreement is being carried out administratively.

The government also notes that the MOU’s $200 billion investment commitment does not carry a fixed deployment deadline. Under the agreement and the pending legislation, investments are designed to be carried out gradually, with annual caps and flexibility built in to reflect commercial viability and market conditions. Officials argue that slower investment spending does not, by itself, mean the agreement is being violated.

Opposition parties, meanwhile, contend that any trade agreement with significant implications for the national economy should receive parliamentary approval, placing responsibility on the government for the current standoff.

The government said it is seeking clarification from the U.S. side on the scope and timing of the tariff increase, while continuing consultations with the Assembly over the next steps.