I first learned to fear law enforcement when I was 9 years old.

I had just arrived in the United States from Mexico without documentation, and I quickly understood that uniforms, sirens, and official questions could change the course of a family’s life. I learned early which streets to avoid, when to stay quiet, and how fear could shape everyday decisions.

After years of obstacles and anxiety, I obtained a work permit through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and became a U.S. citizen in 2019.

Today, I am a family medicine physician with obstetric training, practicing in rural North Carolina. I care for a largely Spanish-speaking, underserved community in a region designated as a maternity care desert, and I train family medicine residents to do this work long after I am gone.

I do not share my story with patients to create trust or connection. Trust emerges more quietly: through careful explanations, respect for hesitation, and the refusal to judge when care is fragmented or delayed. I understand what it means to move through systems not designed with you in mind.

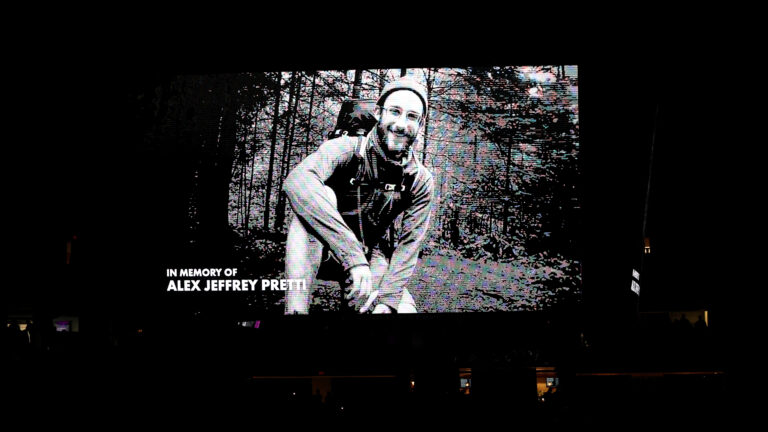

Alex Pretti remembered by health care workers at a Minneapolis vigil as a ‘stand-up guy’

What connects these two chapters of my life is a simple truth: Fear determines whether people seek care.

That is why recent reports of civilians killed during immigration enforcement operations should alarm us not only as a nation, but as a health system. Immigration enforcement is often framed as a legal or political issue. But it’s also something else: a force that quietly reshapes who accesses care, when they present, and whether health systems can function as designed.

In my clinic, enforcement does not arrive with flashing lights. It shows up as missed prenatal visits. As patients who wait until symptoms are severe before seeking care. As pregnant patients who hesitate to go to the hospital — or decline transfer during emergencies — because they fear what might happen on the way. It shows up postpartum, when follow-up is essential and silence can be deadly.

I have watched patients who trusted me deeply still struggle with these decisions. Trust in a clinician does not erase fear of systems. When enforcement looms in the background, even routine care begins to feel risky. This is not about politics; it is about behavior, and behavior shapes outcomes.

The evidence backs this up. Research shows that intensified immigration enforcement suppresses health care utilization, even among U.S. citizen children in mixed-status families. After immigration raids or policy shifts signaling increased enforcement, families are less likely to seek preventive services, prenatal care, or emergency care, leading to delayed diagnoses and worse outcomes. Fear spreads across households and communities, regardless of legal status.

Pregnancy makes these dynamics especially dangerous. The United States already has one of the highest maternal mortality rates among high-income countries, with deaths disproportionately affecting people of color and rural communities. Most pregnancy-related deaths occur after delivery, often because warning signs are missed or follow-up is delayed. Continuity of care saves lives — but continuity cannot exist where fear interrupts access.

Historically, this moment fits a familiar pattern. Periods of intensified immigration enforcement — from the Chinese Exclusion era, to mass deportations during the Great Depression, to post-9/11 expansions of federal authority — have repeatedly framed immigrants as threats rather than neighbors. Each time, the result has been social fragmentation and long-term harm that later generations must repair. Other countries offer similar lessons: Aggressive interior enforcement in parts of Europe has driven marginalized populations away from public services, worsening health inequities without improving safety.

What is different now is how tightly immigration enforcement is intertwined with a health system already under strain. Rural hospitals are closing. Maternity units are disappearing. Workforce pipelines are fragile. In this context, enforcement does not merely frighten individuals — it destabilizes entire care ecosystems. Clinics lose continuity. Hospitals see patients later and sicker. Providers practice in an environment where trust is constantly under threat.

As a physician, I experience this not as ideology but as system failure. Health systems depend on predictability, trust, and timely engagement. Enforcement practices that make patients fear clinics, hospitals, or ambulances erode those foundations. The downstream effects ripple outward: increased emergency care use, more advanced disease at presentation, worse maternal outcomes, and greater strain on already limited rural resources. These are not abstract harms. They are measurable and preventable.

Moving forward does not require abandoning immigration law. It requires acknowledging that public health and immigration enforcement cannot safely occupy the same space. Clear protections for health care settings, limits on enforcement activity near clinics and hospitals, and policies that reassure families they can seek care without fear are evidence-based interventions. Countries that firewall health services from enforcement see better engagement and better outcomes. The United States should learn from that evidence instead of repeating historical mistakes.

My life is often described as an immigrant success story. But that framing is too narrow. The more important story is what happens when fear governs access to care. When immigration enforcement enters exam rooms, labor units, and postpartum clinics, the health system itself becomes collateral damage.

If policymakers continue to treat immigration enforcement as separate from health policy, we will keep missing the stakes — and paying the price in preventable illness and death. The question is not whether immigration law should exist. The question is whether our health system can function when fear is allowed to override care.

Jesus Ruiz, M.D., is a family physician and clinical assistant professor in North Carolina, with a focus on rural maternity care and immigrant health.