While adapting to the rapidly geopolitical changes, Africa has to review its relations with external partners over food security from diverse perspectives. In the current economic context, Africa can demonstrate concern by analyzing distinctive challenges its agricultural sectors currently faces, redesign agricultural production models based on the available resources. In the short term, advocating for food security and debating aspects of adopting import substitution sound as perfect economic measures for Africa. Ensuring economic sovereignty has always been the primary goal since attaining political independence. But, at quick glance, most of these African countries have remained heavily dependent on imports, even a common agricultural item that can be produced locally, and ultimately cutting down budget.

The case in point here is the Republic of Benin. With an estimated population of 14.8 million people, the Republic of Benin situation on the Gulf of Guinea along West Africa, sharing borders with Togo and Nigeria, has an arable land. Its demography shows approximately 45% of the population live urban areas, but the remaining 55% in the rural regions of the country where agriculture is the dominate occupation. A relatively young people, with a medium age of 18 years, and even up to 25 years are very vibrant to undertake modern farming with support from the government.

With sizeable mechanized farming, Benin can produce, at least, to satisfy food requirements and ensure its food security. But it simply cannot due to policy failures. Experts describe Benin as a food-deficit country. Benin has had precarious food and nutrition situation for several years, despite having a stable democracy in the region and in Africa.

Research by this author indicates that Benin heavily imports food because its domestic production, mostly subsistence farming, isn’t enough to feed its population, relying significantly on staples like rice, poultry, fish, and wheat from countries like Russia, India, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Rice: The single largest food import.

Poultry: Frozen poultry meat is a major import.

Fish: Frozen fish is also a significant import.

Wheat & Flour: Essential for bread and other baked goods

Palm Oil & Sugar: other important food items imported.

Benin’s Main Food Suppliers:

India, Thailand, China, Russia, UAE and Brazil, and Togo are the key suppliers.

Basic research shows that during the year of 2024, Benin imports from India worth $658 million, imports from China worth over $500 million, and these include goods such as rice, meat and poultry, alcoholic beverages, palm oil, and other food and agricultural products.

Notwithstanding the long distance involving logistics and haulage, Benin’s imports from Brazil was $37.79 million during 2023, according to the United Nations database on international trade.

Benin and the World Bank:

African and international financial institutions have tried to support Benin to attain food security in the past. For instance, the World Bank launched the Agricultural Productivity Diversification Project (PADA) with the Ministry and Agricultural departments in Benin, with the main objective of supporting farmers to develop a more diverse agricultural sector. In this process, essential farm inputs, such as seeds and fertilizers provided to replant their fields, as well as vaccines, and fish feed to revive both livestock and aquaculture.

These resources ensured that farming families had everything necessary to quickly get back on their feet and resume food production and restore their incomes. With improved practices and modern tools, farmers saw significant increases in crop yields. Harvests of major crops—such as maize, rice and other food products—doubled, providing communities not only with more food but also surplus to sell for cash. The PADA project positively impacted both livestock and aquaculture sectors The project facilitated the development of small-scale processing and storage facilities with increased efficiency.

The PADA has laid down the foundation for new initiatives, to enhance the competitiveness of Benin’s agricultural sector, diversify crop production, and increase both local processing and exports. Ultimately, it generated employment opportunities, improve food security, and strengthen Benin’s food system. Despite these, Benin still face challenges, and unable to turn the challenges into a more sustainable opportunities in the sector.

Why Imports Are Still Necessary:

Subsistence Farming: Most local food production is for immediate family consumption, with little surplus for the market.

Growing Demand: Consumer demand for protein and processed foods outpaces local supply.

Regional Trade Hub: Benin’s port efficiently processes agricultural cargo, much of which is destined for larger markets like Nigeria, highlighting its role in regional food supply chains.

Africa, Benin’s Food Sovereignty with Russia

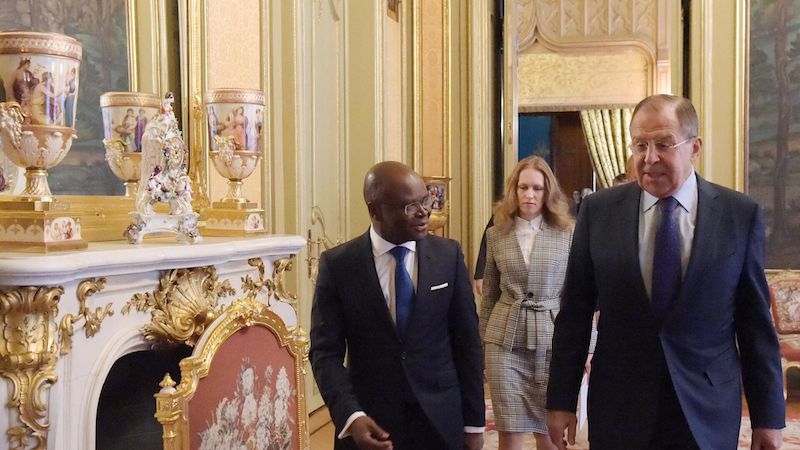

Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov held talks with Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Benin, Olushegun Adjadi Bakari, on the sidelines of the First Ministerial Conference of the Russia-Africa Partnership Forum in Sochi. That was on November 9, 2024. Both ministers discussed ways to strengthen Russia-Benin cooperation in politics, trade, the economy, culture, and other areas, and to improve the legal and contractual framework of bilateral relations.

Later, in Cairo, Egypt, Lavrov appreciated the fact that the Benin Foreign Minister attended with a delegation, and both had a great opportunity to discuss the state of bilateral affairs.

Earlier in late November 2025, Russia’s Ambassador to Benin and Togo, Igor Evdokimov, and Benin’s Secretary-General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Deputy Minister, Franck Armel Afoukou, held fresh discussions on participation in the second ministerial conference of the Russia–Africa Partnership Forum in Cairo. During that discussion, Russian Ambassador, Igor Evdokimov, reiterated strengthening trade and economic cooperation between the two countries. At the meeting, beneficial partnership in investment and, joint exploration and development of natural resources were re-underlined.

Russian poultry exports to African countries in January-August 2025 increased 2.2-fold in physical terms compared to the same period in 2024, and that trend tripled in monetary terms, reaching over $27 million, the Federal Center Agroexport, Russian Ministry of Agriculture, told TASS—the local Russian media. In the reporting period, Russia also exported chicken meat to Africa – frozen chicken and frozen turkey.

According to Agroexport, the top five African countries importing poultry meat from Russia by value are Benin, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Gabon, and Guinea. During this period, Russian poultry exports to Ghana increased by 6.5 times in monetary terms, to Benin by 6 times, and to the Democratic Republic of Congo by 1.5 times.

In 2025, Russia also exported poultry to the Central African Republic for the first time and resumed deliveries to Togo after a hiatus since 2023, according to Agroexport. Since Jan. 2026, Russia has launched wheat exports to Togo and Benin in West Africa. Egypt, Algeria and Kenya are also among the top buyers.

Where lies the food sovereignty then? Many African countries, including Benin, have emerged as a key importing-partners in this import deals from private Russian exporting companies, endorsed by the Russian Ministry of Agriculture. The current bilateral relationships and economic cooperation allows the Federal Center Agroexport, Russian Ministry of Agriculture, to create the ‘golden opportunity’ to increasingly earn revenue from Africa’s lack of using their own resources to produce food for local consumption.

At its core, many political elites and corporate entrepreneurs remain largely cautious over the state’s decision to depend on imports. The traditional mathematics is always simple: write the checks and have a varying part of the share. That’s the implication of write the cheques, shouting and reiterating food self-dependency in official well-colored speeches is just mere political rhetoric.

As it is the case from the time of gaining political independence, Africa will never attain food sustainability and ensure food sovereignty, if long-term interests are based on what Russia always offers during bilateral talks. Offers have to be cautiously examined, discussed and negotiated. Multipolar rhetorics and historical Soviet-era solidarities should not be the basis to turn Africa into import-dependency partners.

The Way Forward into Future

As Russia heads for the third Summit, African leaders have serious review Russia’s earlier food security pledges, which are contained in official declarations in Sochi (October 2019) and St. Petersburg (July 2023). Economic policy experts have suggested Africa increasingly adopts import substitution policies and intensifies domestic production. It has adequate resources, at least, to engage in improving its local production, modernizing agriculture while extending financial support for local farmers. Public-private partnerships, as one key aspect, aim at employment creation and support for food security is absolutely necessary.

The path forward lies in rethinking the Russia–Africa agricultural dynamic—shifting from dependency toward resilient, locally driven food systems. Building internal agricultural capacity is the surest path to resilience and food sovereignty. The path to sovereignty is not paved with huge imports, but rather with bold investment in homegrown solutions. It is important to mechanize food production, create employment and be self-sufficient in this sphere.

In this changing era, food security is no longer merely a development issue—it is a cornerstone of national security, economic independence, and global standing. For Africa, the time to act is now.