A defining moment came on 16 January 2026, when Greece’s newly launched Earth-observation micro-satellites — part of the National Microsatellite Programme under the Ministry of Digital Governance — successfully captured images of the Hellenic Navy frigate Kimon sailing in the Saronic Gulf, underscoring the country’s growing ability to monitor, protect and project sovereignty from orbit.

This development reflects Greece’s expanding presence in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) and signals a deliberate effort to establish sovereign space-based reconnaissance and intelligence capabilities that were previously absent. The operationalisation of these microsatellites offers high-resolution imaging across the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean, covering a region characterised by heavy maritime traffic and complex security dynamics.

The launch of five micro-satellites on 28 November 2025 followed the earlier deployment of DUTHSat-2, Greece’s first domestically developed nanosatellite by the Democritus University of Thrace, launched on 23 June 2025 with support from the European Space Agency (ESA) and the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Fund (RRF). This nanosatellite marked Greece’s first homegrown contribution to environmental monitoring and disaster response, providing valuable data on soil moisture and marine pollution.

The November mission included two X-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR)-equipped satellites developed by ICEYE — part of ESA partnerships — capable of delivering day-and-night high-resolution imagery (up to 25 cm) for both civilian and dual-use purposes. These SAR capabilities enhance Greece’s situational awareness, especially in areas frequently cloud-covered or where optical imaging alone is insufficient.

Among the constellation launched were additional experimental cubesats, such as the Maritime Identification and Communication System (MICE-1) developed by Prisma Electronics, aimed at enhancing maritime domain awareness in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean. Two further experimental satellites, PHASMA (LAMARR and DIRAC), developed by the Libre Space Foundation, were designed to monitor ultra-high and S-band frequencies to support national telecom and spectrum security efforts.

A critical strategic partnership enhances these developments: an agreement between the Hellenic Space Centre, the Greek Ministry of National Governance, and the Finnish micro-satellite company ICEYE allows Greece to utilise ICEYE’s radar imagery from its global SAR satellite constellation. With ICEYE boasting one of the world’s largest SAR fleets, this partnership ensures persistent coverage over Greek areas of interest, facilitating long-term and repeated surveillance critical for both environmental monitoring and defence.

Looking ahead, Greece plans to launch a total of 13 to 15 microsatellites by 2030, which will create a foundational Greek presence in LEO and enable inter-satellite links with geostationary platforms. This integrated approach will support the broader GreeCom programme, intended to unify satellite communications and data relay capabilities for civil and defence users.

A parallel pillar of Greek space infrastructure is the Hellas-Sat geostationary satellite system at the 39° East orbital slot. These SATCOM platforms — beginning with Hellas-Sat 1 in 2002 and followed by Hellas-Sat 2, 3, and 4 — have provided essential communications services, broadcasting and secure bandwidth for Greek government and military operations. This geostationary infrastructure forms a core strategic asset, enabling secure satellite communications across Europe, the Middle East and Africa and supporting both civilian and defence functions.

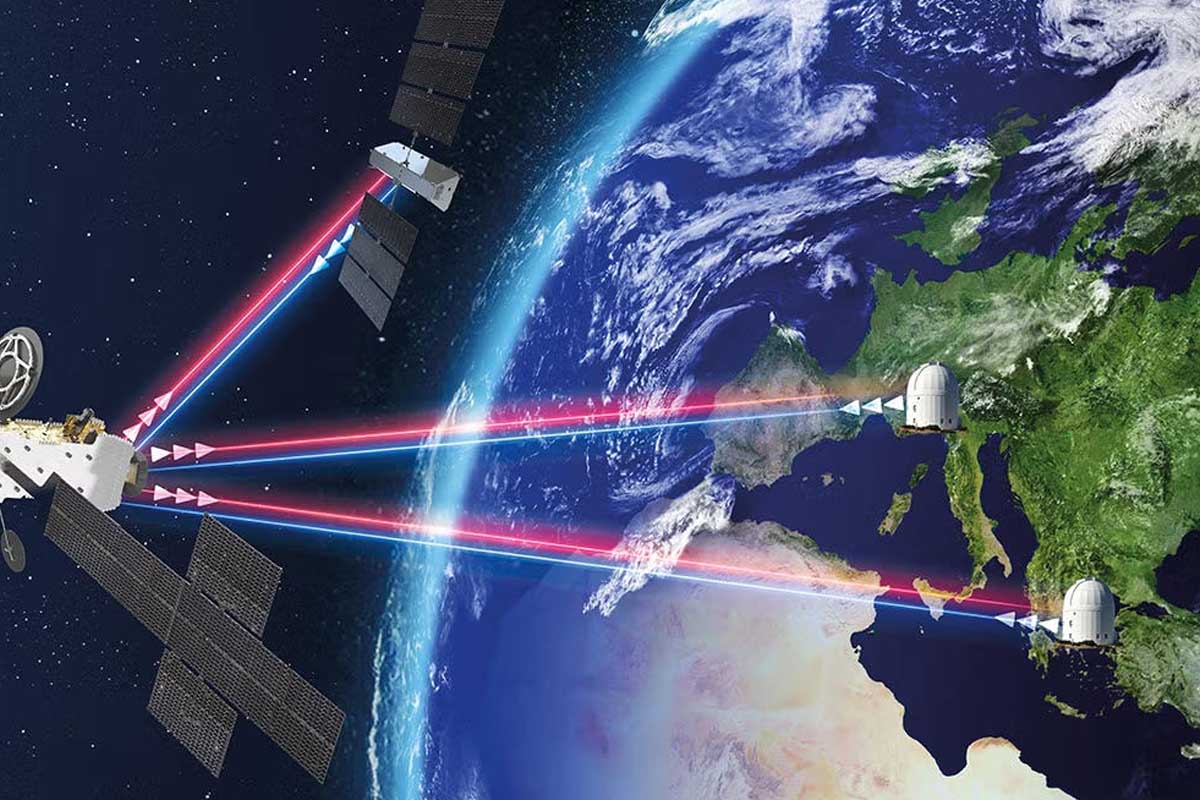

Ongoing developments include the Hellas-Sat 5 project, undertaken with Thales Alenia Space, which will feature optical communications payloads and a network of ground nodes — including observatories in Kalamata, Crete, Chalkidiki and Corinthia — offering quantum-enhanced SATCOM security against jamming and electronic warfare threats. This expansion is aligned with the European Quantum Communication Infrastructure (EuroQCI) initiative, intended to establish secure quantum-encrypted communications across EU member states.

Hellas-Sat’s geostationary position enhances resilience against anti-satellite threats, while development plans aim to interlink GEO and LEO systems to enable faster and more versatile data relay. Such integration is vital for a resilient national space architecture capable of serving government departments, defence organisations, and civilian agencies during crises or conflict scenarios.

Overall, the article illustrates that Greek spacepower is rapidly transitioning from conceptual ambition to operational reality. The combination of microsatellite constellations, strategic partnerships, and a strengthened SATCOM backbone not only fills a long-recognised gap in national capabilities but also positions Greece for sustained engagement with the global space economy — a sector valued at hundreds of billions of dollars annually.