Following the capture of Nicolas Maduro in a raid by US forces in Caracas on the night of January 3, Venezuela is entering a transition phase in which oil is no longer just the country’s main economic asset, but also the instrument through which alliances are being rewritten, trade routes reconfigured, and the limits of sanctions policy tested.

Paradoxically, what is happening in Caracas is quickly becoming an energy security issue for the United States, a geopolitical balancing act for China, and an uncomfortable variable for OPEC+, which is already engaged in the delicate task of preventing a global oversupply.

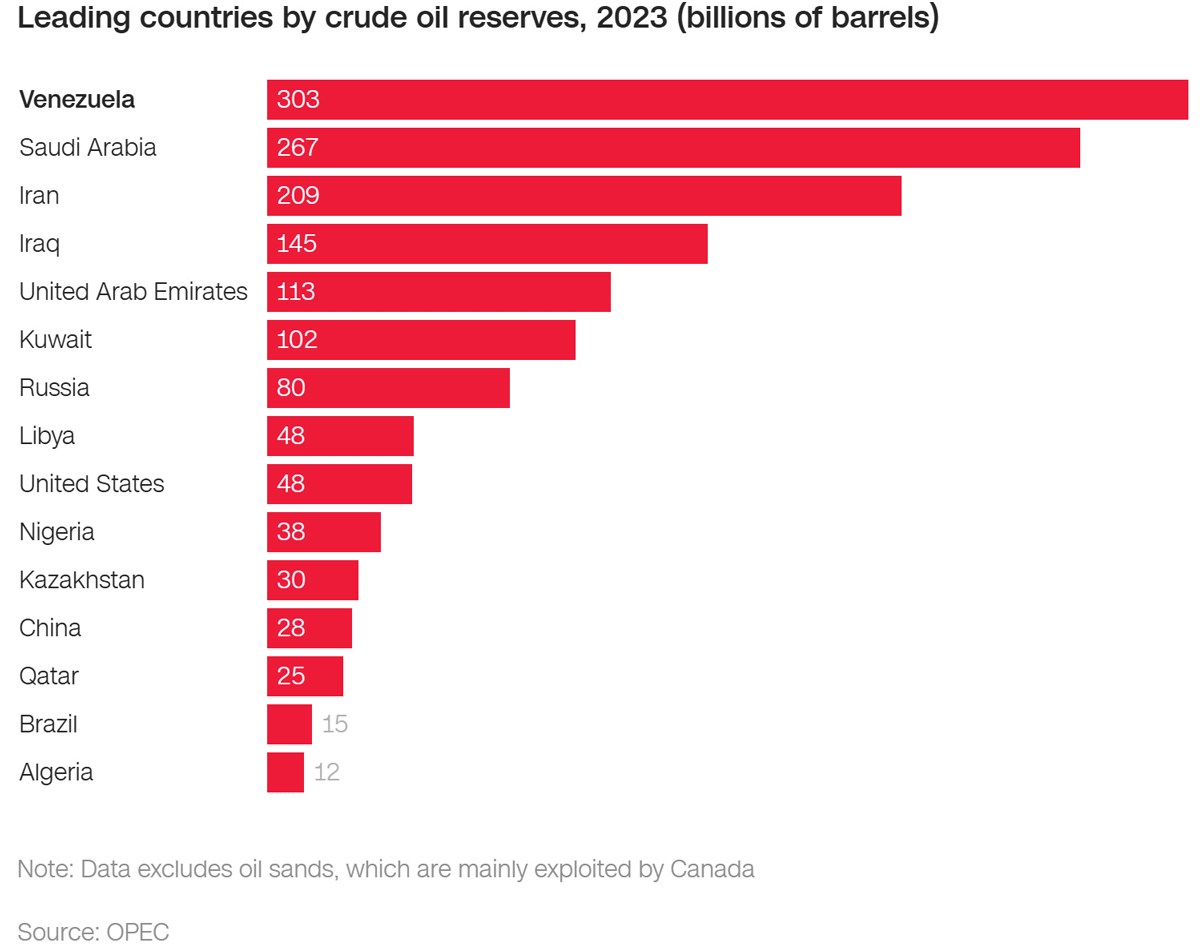

Against this backdrop, Venezuela’s National Assembly approved, in its first reading, a bill that fully opens up the country’s oil reserves—described as the largest in the world—to private companies. Until now, the oil extraction sector had been exclusively state-owned, with only joint ventures in which the state held a majority stake being permitted. According to available information, the new law would allow private companies based in the Republic of Venezuela to extract oil after signing contracts, but the reform must also be approved in a second reading to come into force.

It is a major political signal: from a model dominated by the state and controlled by the oil company PDVSA to a model that seeks to attract private capital, in a country with a deteriorating oil infrastructure, historically declining production, and a governance system undergoing a sudden transition. The legislative change is superimposed on one of power and an accelerated diplomatic repositioning: Maduro has been flown to the US and is being held in custody in New York to stand trial with his wife on drug trafficking charges. Vice President Delcy Rodriguez is acting as interim president and is presented as having much better relations with Washington, having already been invited to the White House for a meeting with Donald Trump. The US has also appointed a new chargé d’affaires in Caracas, marking a thaw in bilateral relations. In this logic, oil liberalization does not appear as an isolated economic reform, but as a mechanism for rebuilding internal legitimacy and negotiating a new external anchor.

Who bought Venezuela’s oil before: Two markets, over 90% of exports

Before the industry entered this geopolitical “laboratory,” Venezuela’s exports had a surprisingly concentrated structure. In 2023, Venezuela exported 211.6 million barrels of crude oil, with over 90% of the volume going to just two countries: China and the United States. According to the data cited and a Visual Capitalist summary, China was the main destination, importing approximately 144 million barrels in 2023, equivalent to 68% of Venezuela’s total exports. The US was the second biggest buyer, with 48.5 million barrels (23% of the total). Spain and Cuba followed with significant volumes: 8.5 million and 7.6 million barrels respectively.

This export geography tells us two essential things about “oil-rich Venezuela” in recent years. First: the country basically operated with two major trade “pipelines,” one to the East (China) and one to the West (the US), with all other destinations being secondary. Second: although sanctions and political tensions have changed the mechanisms of sale and payment, the basic logic—two large absorption centres—has remained constant.

When the United States openly talks about taking control of how PDVSA markets crude oil and oil revenues, the geopolitical blow is aimed not only at the internal regime, but also at the “export equation” that has kept Venezuela alive: reducing dependence on China and cutting off the financial “oxygen” provided by oil-credit arrangements.

Why China has become the main partner: Oil for credit, not cash

Following sanctions imposed on PDVSA by the United States in January 2019 during Trump’s first term, the state-owned oil company was effectively excluded from the US financial system and normal cash sales. At that time, a major part of Venezuelan exports shifted to oil-for-credit arrangements. China has become the main partner in these transactions: it has granted Venezuela loans of nearly USD 50 billion over the past decade, with a balance now estimated at USD 10–12 billion, and repayment has been made through deliveries of crude oil instead of cash payments. The scheme was a safety net for Venezuela in financial isolation. For China, it was a decision between securitization of resources and loan recovery through a tangible asset. Moreover, the characteristics of Venezuelan oil played in Beijing’s favour. The heavy crude oil produced by Venezuela is more difficult to refine and generates fewer high-value products (gasoline and diesel), producing more residues such as bitumen. For China, however, this profile was advantageous: high demand for bitumen was fuelled by large-scale infrastructure and construction projects, and Venezuelan crude oil provided a relatively inexpensive source for these needs.

This gives rise to a strategic risk: if the United States consolidates its control over the Venezuelan oil sector, China will be forced to compensate not only for the loss of volume, but also for the loss of a type of crude oil that is suitable for its “bitumen economy” and infrastructure. And the natural replacements are Russia, Iran, and—potentially—Canada, which also produces very heavy crude oil. Basically, any shift in China’s focus is either toward partners that are already sanctioned or controversial (Russia, Iran), or toward a stable supplier with logistical and commercial constraints (Canada), which could push up prices and reshape routes.

The American paradox: Why the US wants Venezuelan oil when it produces so much of its own

The question that comes up obsessively in public discussion is: why would US refiners need Venezuelan crude oil if the US pumps more oil than any other country? Although the shale drilling boom has unleashed a wave of oil from places such as West Texas and North Dakota, it is often not the right type of crude for some US refineries, which were designed decades ago to process heavier crude—the kind traditionally imported from Canada, Mexico, and Venezuela. In total, about 40% of the oil that passes through US refineries is imported to get the right “blend” of crude oil to make different products. In recent years, Venezuela’s production has plummeted and what little oil it does produce has been diverted largely to countries like Cuba and China. At the same time, excess oil pumped by the US was shipped overseas after the lifting of the crude oil export ban about a decade ago, and America has since become one of the world’s largest oil exporters.

From this perspective, interest in Venezuela has an industrial basis: heavy crude oil for refineries designed for this heavy crude oil. But the Trump administration seems to be going much further than mere “input optimization.” The plans discussed indicate a broad initiative to dominate the Venezuelan oil industry for years to come, with two primary objectives: excluding Russia and China from Venezuela and making energy cheaper for American consumers. Trump has even suggested that his efforts could lower the price of oil to his preferred level of USD 50 a barrel. But here a structural tension emerges: for a large part of the US oil and gas industry, USD 50 a barrel is a threshold below which drilling becomes unprofitable. In other words, what sounds good politically for consumers can sound bad economically for producers. The administration is trying to overcome the reluctance of US producers to extract even more by extending the “drill, baby, drill” mantra beyond US borders in a way that shifts costs and risks to an unstable jurisdiction.

What “American control” over PDVSA means: Money, licenses, trading and accounts

In concrete terms, the plan under discussion would involve the US exercising some control over PDVSA, including over the purchase and commercialization of most of its production. In the advanced scenario, the proceeds from the sale of Venezuelan oil would be transferred to US-controlled bank accounts “for the time being,” to be distributed later to the Venezuelan interim authorities. Energy Secretary Chris Wright explained this mechanism, and Trump said that Venezuela would purchase American products with the proceeds from oil sales.

Following the same logic, sanctions against Venezuela would be selectively lifted to allow the trade of sanctioned oil. Trump said Venezuela would supply the US with between 30 and 50 million barrels of sanctioned oil, and the energy secretary said the US would sell Venezuelan oil “indefinitely.”

This model resembles more a “trade protectorate” than a free market: control over oil flows, control over revenues, selection of eligible companies, licenses for traders, plus a financial architecture in which money is held in an account “with an American key.” The implicit message to the rest of the world is that the US not only influences the oil market through its own production but may end up directly controlling a significant portion of the reserves and exports in the Western Hemisphere.

Market reality: Venezuela is already cutting supply, OPEC cuts, OPEC+ puts the brakes on

On paper, the US plan promises “more oil, lower prices.” In the immediate reality of the market, the signal is the opposite: supply is tightening. Aggregate OPEC deliveries fell in December 2025, and OPEC production declined amid reduced deliveries from Iran and Venezuela, which offset the OPEC+ agreement to increase production for this period. According to a Reuters survey, OPEC countries pumped an average of 28.40 million barrels per day in December, about 100,000 barrels per day less than the revised November level. The largest decline was recorded by Iran, subject to US sanctions aimed at limiting exports in the context of its nuclear program, with measures announced in December.

OPEC+ has slowed the pace of monthly production increases amid fears of a surplus. Many members are already producing at quota limits, and some must apply additional reductions to compensate for previous overproduction, which limits the effect of increases “on paper.” Under an agreement between the eight OPEC+ members for December, the five OPEC members involved (Algeria, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) were supposed to increase production by 85,000 barrels per day, before the compensatory cuts of 135,000 barrels per day assumed by Iraq and the UAE. But the Reuters poll shows that the actual increase was only 20,000 barrels/day.

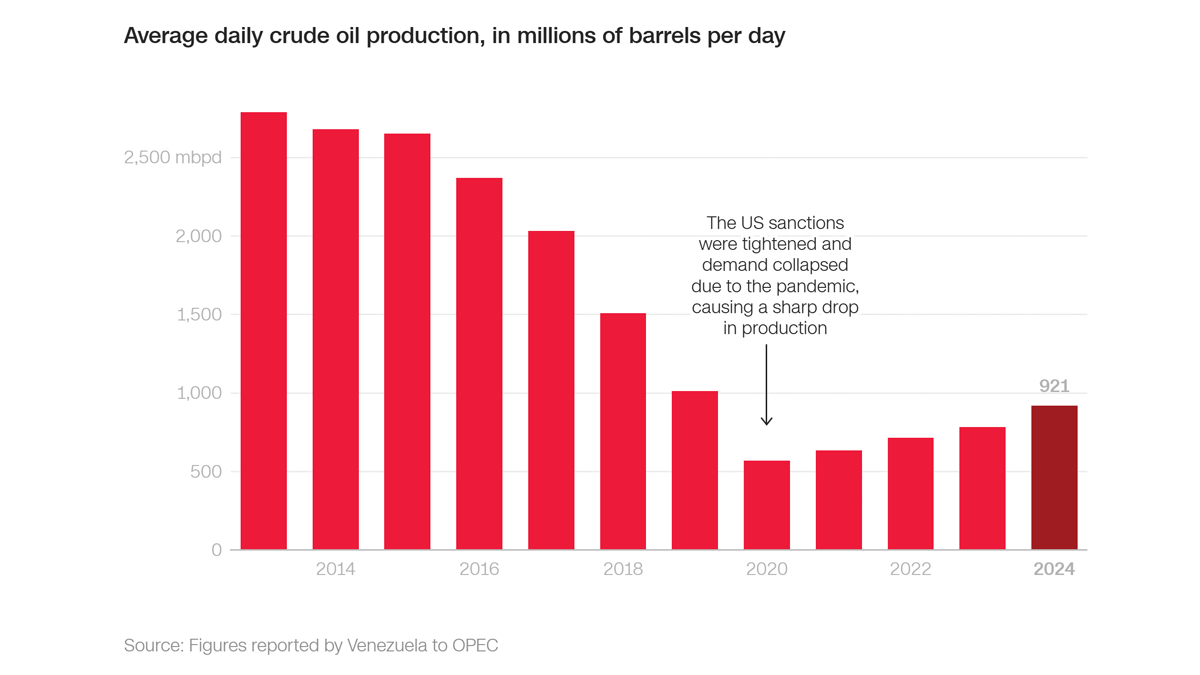

In this context, Venezuela appears as a variable that is dragging down supply. Its production fell by about 70,000 barrels per day in December amid a US blockade to reduce oil shipments, with the impact expected to intensify. One estimate indicates a decline in crude oil and condensate production to 950,000 barrels per day in January 2026, from 1.1 million barrels per day in December 2025. More dramatically, vessel tracking data and PDVSA export records show that Venezuela’s exports of crude oil and residual fuels averaged 952,000 barrels per day in November and fell to 498,000 barrels per day in December, with the difference being directed to land and floating storage.

So, before legislative liberalization could produce results and American investments could restart infrastructure, Venezuela had already become a factor in the decline of exports. For the market, this means upward pressure on prices, not downward, at least in the short term. And for the Trump administration, it means that the USD 50/barrel target is, in the initial phase, difficult to sustain without a rapid increase in flows.

Why big companies are sceptical: Huge investment, political risk, “uninvestable” today

In this whole story, the element that decides whether Venezuela remains just a geopolitical issue or becomes a real generator of supply is investment. Increased production would require tens of billions of dollars of investment from US companies, which are reluctant to do so. Companies demand “serious guarantees” from Washington before making major investments. In discussions with top executives, Trump said he would personally decide which oil companies would be allowed to enter Venezuela and that American companies would spend “at least USD 100 billion of their own money” to revitalize the infrastructure. The amount was met with scepticism from industry sources.

During a meeting at the White House, giants such as ExxonMobil, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips indicated that they want security guarantees before committing. ExxonMobil’s CEO explicitly said Venezuela is currently “uninvestable.” ConocoPhillips has not committed to operating there, and a Chevron official detailed current operations without promising an expansion. Trump responded that the US would provide protection and work with the Venezuelan government, and that companies could ensure part of their own security.

Scepticism has a simple logic: even if you have access to the largest reserves, they cannot be turned into exportable barrels without functional infrastructure, oil services, the necessary logistics, and a stable legal framework. And in Venezuela, all these components are currently being challenged by instability, political transition and uncertainty about the future of the ruling regime.

At the same time, Reuters points to intense competition for Venezuela’s existing crude oil marketing licenses between firms such as Chevron, Vitol and Trafigura, suggesting a difference between “short-term trading” and “long-term investment.” Traders can operate in windows of opportunity, under licenses and waivers; large companies, which invest tens of billions in fields and refineries, need multi-year stability.

The new law: Internal liberalization, but under an external “cap”

The bill approved in its first reading promises complete openness to the private sector, but the relevant detail is that it mentions the possibility of private companies based in Venezuela extracting oil after signing contracts. In a country trying to avoid the perception of “selling off its resources,” this wording could create a framework in which private capital gradually infiltrates through local entities, consortia, legal vehicles, and subcontractors, while control over large flows and revenues is exercised through the licensing and accounting mechanisms discussed by Washington.

Thus, “complete openness” risks being, in the first phase, incomplete openness in practice: largely private at the level of services and logistics, but tighter control at the level of exports and money.

Immediate regional effects: Winners and losers in the coming months

1) Cuba imported 7.6 million barrels in 2023, a relevant volume for an energy-dependent economy. If Venezuelan flows are redirected to the US and Washington-licensed channels, Cuba’s access may become more expensive, scarce or politicized. In the region, any disruption in supplies quickly translates into social tensions and economic constraints.

2) China, the main buyer of Venezuelan oil, will have to replace the type of heavy crude useful for bitumen demand. Most likely, it will increase imports from Russia and Iran. But this amplifies precisely the geopolitical dependencies that Washington is trying to reduce. If Beijing shifts a significant portion of its demand to the “sanctioned zone,” tensions in payment mechanisms, transportation and insurance will increase, and the market may become more fragmented between “clean” and “shadow” flows.

3) Venezuela’s neighbours—through oil service firms, logistics, ports, transport—may benefit indirectly. But this opportunity depends on the political stability of the interim government and the ability of officials in Caracas to sign coherent contracts.

Three likely scenarios for the next 6-12 months

Scenario A – “Stabilization under licenses” (most likely in the short term): The US selectively lifts sanctions, grants trade licenses, and stabilizes exports by controlling trading and revenues. Production remains modest, but exports have been rising since December (when they fell to 498,000 barrels per day) to a level closer to November (952,000 barrels per day), as stocks are depleted and logistics normalize. China is losing volume and turning to Russia/Iran. Overall prices remain relatively stable, with episodes of volatility.

Scenario B – “Investment deadlock” (likely if instability persists): Major companies remain cautious, demanding guarantees that cannot be offered quickly, and Venezuela remains “uninvestable” in the Exxon sense. Legislative liberalization produces more noise than barrels. Supply remains constrained, OPEC+ is managing a fragile balance, and the USD 50/barrel target is becoming policy rhetoric, not market outcome.

Scenario C – “Accelerated recovery” (less likely but possible if the regime and guarantees are strengthened): If Delcy Rodriguez’s interim government gains internal legitimacy and external support, if the law is finalized in the second reading, and if the US offers a robust package of legal and security guarantees for companies, significant investments can begin. But even here, the effect on production comes with a lag: months for repairs and restarts, years for big projects. Politically, the Trump administration could claim success, and economically, the market would feel the gradual effect.

A new model for “political oil” in the Western Hemisphere

Venezuela is at the beginning of a reconfiguration in which internal liberalization and external control are taking place simultaneously. On the one hand, the National Assembly approves (in first reading) a law opening up exploitation to the private sector, breaking a taboo of state control. On the other hand, Washington is discussing a mechanism whereby PDVSA would sell oil under conditions whereby revenues would go into accounts controlled by the US, under licenses and company selections, with the promise of a selective lifting of sanctions and with an explicit political goal of lowering oil prices.

At the heart of this change are three tensions that will determine the next direction: US-China tensions, with Beijing losing access to a type of crude oil and a barrel-based repayment scheme; Washington trying to take China out of the game, but risking pushing China even closer to Russia and Iran. Secondly, the tension of the USD 50/barrel price promise helps the consumer but may hit the profitability of US producers and reduce the appetite for drilling. Thirdly, without guarantees, Venezuela remains “uninvestable” and without investment, the law remains symbolic, and without barrels, geopolitics remains rhetoric.

Predictably, the next few months will be dominated not by big investments, but by the battle for licenses, export controls and the rapid redistribution of flows between China, the US and secondary players. At the regional level, the most visible immediate effect will be who receives the barrels and who loses them—only then, over a longer horizon, will it matter whether Venezuela can become a stable supplier again or remains a battleground between sanctions, transition, and strategic interests.