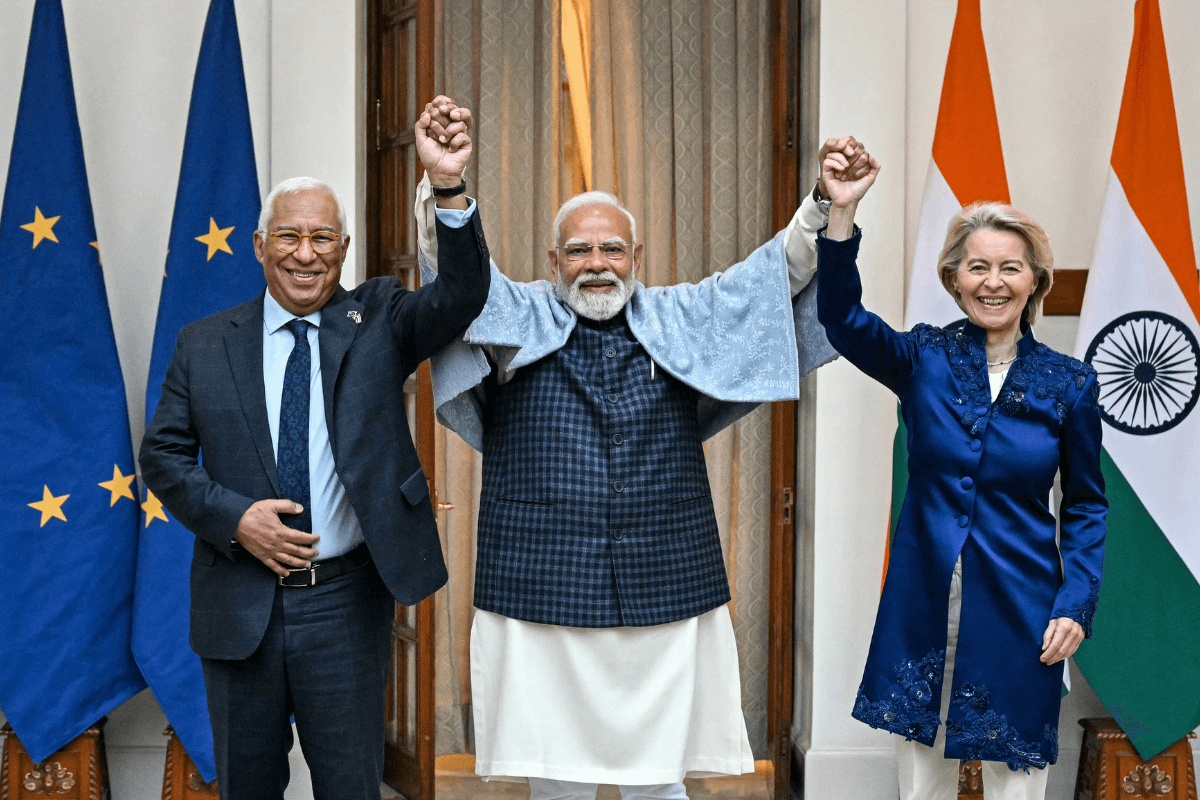

On 27 January 2025, the European Union and India signed a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in New Delhi, bringing to a close nearly 20 years of negotiations. It will bring together two economies representing roughly a quarter of the world’s population, 25% of global GDP and a combined market of almost 2 billion people. With bilateral trade in goods and services already worth €180 billion, the FTA aims to double EU exports to India by 2032. Given the scale of the numbers involved, and with India widely expected to overtake Japan as the world’s fourth largest economy, it is little surprise that European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen descried the agreement as the “mother of all deals”.

Yet the EU–India FTA is less about economics or diplomacy than about geopolitics. Its conclusion has been driven in large part by shifting geopolitical pressures from Washington and Beijing, which have forced both Brussels and New Delhi to reassess their strategic positioning.

For years, as negotiations stalled, EU–India relations drifted without a clear geostrategic anchor. That changed as global relations sharply shifted with the return of Donald Trump to the White House and amid China’s growing assertiveness across critical supply chains. These developments compelled Brussels and New Delhi to rethink their exposure to these strategic risks.

Trump’s renewed threats of tariffs, most recently over Greenland, have forced the EU to confront the limits of its reliance on the US. Securing alternative markets is not only an economic calculation, but a geostrategic necessity. India, with its vast consumer market, youthful population and expanding manufacturing ambitions, stands out as a particularly attractive alternative. This FTA could serve as a template for future trade deals with countries seeking to hedge against overdependence on the US and China.

India, too, has been exposed to the risks of Washington’s increasingly transactional foreign policy. A long-time proponent of the rules-based international order, one that has underpinned its rapid economic growth, New Delhi found itself vulnerable under the revived “America First” agenda. The previously warm personal relationship between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Trump proved an inadequate shield against rapidly deteriorating ties, highlighting the limits of Modi’s personalised diplomacy.

The pivotal moment came in June 2025, when Trump claimed credit for ‘solving’ the India–Pakistan military crisis and sought Nobel nominations. Pakistan complied; India refused. Endorsing Trump’s narrative would have risked undermining Modi’s domestic strong man image and India’s insistence on bilateral crisis management. His refusal signalled a calculated assertion of strategic autonomy.

Washington’s subsequent resort to economic pressures reinforced this reassessment. Successive rounds of tariffs, including measures targeting India’s purchases of Russian oil for refining and re-export, culminated in duties of a combined 50%. In New Delhi, these moves were widely seen as punitive and hypocritical, particularly given China’s exemption despite far larger imports of Russian energy. The episode accelerated India’s strategic recalibration, strengthening the case for diversifying economic partnerships and reducing exposure to an increasingly unpredictable US.

The EU and India also face converging geostrategic challenges in their dealings with China, making the FTA strategic, not merely economic. While neither side can afford full decoupling from Beijing, deeper EU–India economic integration could help mitigate vulnerabilities linked to trade imbalances, technological dependence and critical digital infrastructure. For India, these concerns are sharpened by China’s role as a major defence partner of Pakistan and by the unresolved border dispute dating back to the 1962 war, which continues to generate periodic military tensions. In this context, the FTA functions less as a mechanism for strategic risk reduction than as a political catalyst for strengthening resilience and autonomy.

Crucially, the FTA was accompanied by a new security and defence partnership, adding another layer to the relationship. The partnership establishes a framework for cooperation across maritime security, cyber resilience, counterterrorism and defence-industrial collaboration. For New Delhi, this offers enhanced maritime coordination with European navies, access to advanced European defence technologies and defence-industrial investment, and deeper cooperation on cyber and hybrid threats. It also helps India reduce its dependence on Russian arms supplies and elevates India’s diplomatic standing within the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy.

However, tensions remain. One of the partnership’s key challenges will be the EU’s expectation that India distance itself from Moscow, an outcome for which New Delhi has little appetite. The partnership spans over five decades, during which Moscow repeatedly backed India’s control over Kashmir at the UN Security Council, support that remains valuable for a country without a permanent seat.

Taken together, the EU–India FTA and the accompanying security partnership represent a strategic bet on a more balanced and diversified global economic and security architecture. They reflect a shared geopolitical reality that as mid-level powers, neither Brussels nor New Delhi can navigate an increasingly fragmented international landscape alone. Whether these agreements evolve into the foundation of a deeper and more durable partnership will depend on sustained political commitment – and a willingness of both sides to exercise regulatory pragmatism.

Rajnish Singh is a Media Outreach Executive at the EPC Communications team.

The support the European Policy Center receives for its ongoing operations, or specifically for its publications, does not constitute an endorsement of their contents, which reflect the views of the authors only. Supporters and partners cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.