In a world charged with racial resentment and ethnic tension, the town of Kawaguchi does not feel like a community on the edge. It looks like hundreds of other satellite towns an hour from Tokyo — busy, prosperous, uneventful and extremely safe.

Commuters come and go in the railway station, which is surrounded by the usual neighbourhood of bars, cafés, department stores and love hotels — only an exceptionally alert observer would detect a higher than average number of kebab restaurants.

But despite appearances, Kawaguchi is at the centre of a bitter, noisy and occasionally violent argument about a subject that until a few months ago was scarcely discussed in Japan: immigration, and the place of foreigners in a society where they were once almost invisible.

All of last week, vans with mounted loudspeakers stopped in front of Kawaguchi railway station blaring out speeches by political candidates competing in two separate elections. Rather than the surging cost of living, or the threat from an increasingly aggressive China, they are dominated by what is referred to as “the foreigner problem”.

“Japan belongs to the Japanese people,” said Keigo Furukawa of the right-wing Nihon Yamato Party, who stood in Sunday’s election for mayor of Kawaguchi before next Sunday’s national parliamentary election. “We don’t need illegal immigrants, fake refugees, or foreigners who try to destroy Japanese culture and traditions.”

The candidate of Nihonto (Japan Party), Toshikazu Nishiuchi, insists that the streets of Kawaguchi are no longer safe. “Immigration is what people here are most worried about,” he said. “There are many problems. There are problems with rubbish, traffic accidents and crimes, including sexual crimes. These people do not follow the rules.”

Who are these people? Statistics show that 48,000 of Kawaguchi’s 607,000 people are foreigners — 8 per cent of the total and a good deal higher than the national figure of just over 3 per cent. More than half of foreign residents in Kawaguchi are Chinese, followed by Vietnamese and Filipinos. But public attention is entirely focused on a much smaller and more obscure group — Kurds from eastern Turkey.

Almost all of Japan’s Kurds live in Kawaguchi and the neighbouring town of Warabi, a total of just 2,000 people or so in the two municipalities. They began arriving in the 1990s at a time when armed conflict between the Turkish government and the pro-independence Kurdistan Workers’ Party was at its peak.

Nihonto officials canvas outside Kawaguchi Station on Saturday

SHOKO TAKAYASU/EYEDENTITY

For years, they lived quietly, many of them working in the demolition business or in restaurants serving Turkish and Kurdish food. But in the past three years, they have become objects of suspicion, dislike and outright hatred.

Happy Kebab in Warabi

SHOKO TAKAYASU / EYEDENTITY

The hostile messages of the hard-right politicians are mild compared with the worst of the hate speech. Tatsuhiro Nukui, head of a community organisation that provides Japanese classes to Kurdish children, has received hundreds of phone calls, letters and emails, many of them with messages of violence. “We’ll kill you all and feed you to the pigs,” read one anonymous message. “Massacre all Kurds!”

Police are investigating the case of a Japanese man accused of hitting a Kurdish primary school boy who was playing in a park last July. Confronted by his father, who filmed the encounter, he shouted: “If it wasn’t against the law, I’d kill you.”

Anonymous social media users post sneering comments online about “Warabi-stan” and videos of Kurdish people going about their daily lives, including a four-year-old girl accused of “shoplifting” in a supermarket.

“People are now afraid of being recorded,” said Vakkas Colak, a university lecturer who runs the Japan Kurdish Cultural Association. “Even me now — [when] I am riding the trains, I am looking around ten times to check if somebody is taking a video. It has had a huge impact on me, on my daily life.”

Volunteers teach Kurdish children Japanese in Warabi

SHOKO TAKAYASU / EYEDENTITY

The hate speech surged after an incident in 2023 when a knife fight took place in Kawaguchi between two groups of Kurdish youths. In separate cases, two Kurdish men have been accused of rape. But there is no reason to believe that Kurds are driving any kind of crime wave.

The total number of crimes committed in Kawaguchi city in 2024 was less than a third that in 2005; the number of foreigners has increased from 15,000 to 48,000. The Kurdish population in Kawaguchi has gone from 190 to 1,500.

When asked, the complaints most often cited by local Japanese are comically trivial. Kurds are accused of “being noisy”. They are reproached for failing to follow Japan’s complicated rules about how to divide up and put out for collection different kinds of household rubbish.

Asked what troublesome behaviour by foreigners he has encountered in his own life, Nishiuchi, the candidate for mayor, hesitates before remembering an occasion when he saw a man driving his car erratically. “From his appearance I knew he was a Muslim,” he said. “Someone who drove like that could not be Japanese.”

It remains to be seen how all this will play out at the national level. In elections to the upper house of Japan’s Diet last summer, the anti-immigration Sanseito party won 14 seats. But when the Japanese choose MPs for the more powerful lower house next Sunday, the ultra-right may find itself outflanked by the prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, leader of the ruling conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

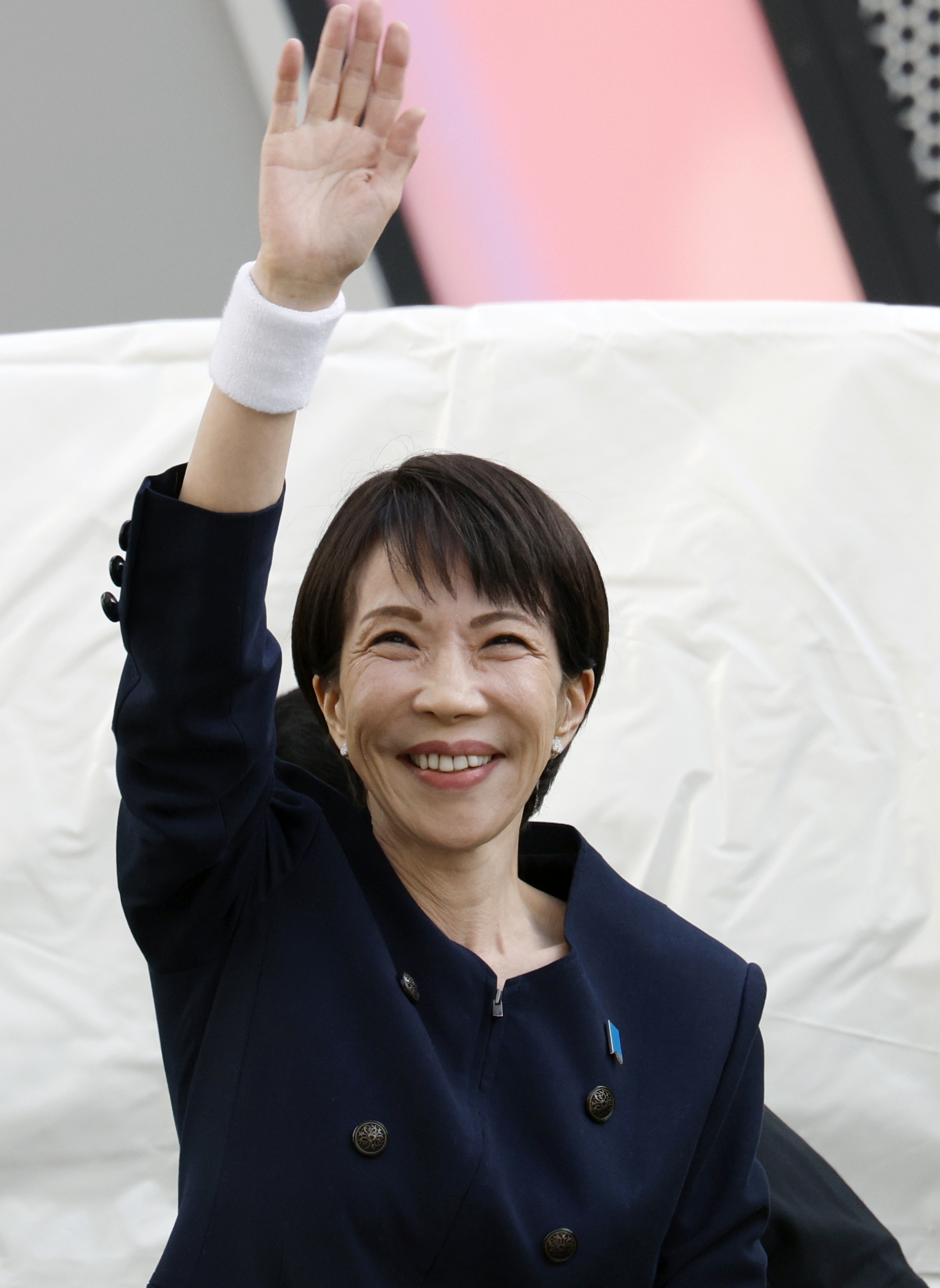

Sanae Takaichi at a rally in Tokyo

FRANCK ROBICHON / EPA

Polls published on Monday suggest she is riding a wave of personal popularity to a landslide victory, and that the LDP and its coalition partner will win 300 or more of the 465 seats in the Diet, at the expense of the centrist opposition and far-right parties.

Takaichi avoids the crude racism of the small nationalist parties, but since becoming leader last autumn she has achieved high approval ratings by, among other policies, committing to “zero illegal immigrants”.

• Young voters go wild for Japan’s stylish, mould-breaking PM

None of this will help with one of Japan’s chronic problems: the shrinking workforce caused by the nation’s ever-falling birth rate.

The arbitrariness of choosing Kurds as a target and the triviality of many of the complaints against them suggests that ill-feeling towards foreigners is a proxy for deeper and more complex insecurities about a future of economic and military insecurity.

“Foreigners are not the problem in Japan,” Colak said. “The problem is the ageing society, and stagnation in the economy for 30 years, and a politics that cannot give anything to the people. To escape from these economic [and] political issues they try to create a problem that doesn’t exist.”