Since the time of Kim Il Sung, North Korea has sought to compensate for its mountainous terrain and shortage of arable land through tideland reclamation.

After Kim Jong Un assumed leadership, land reclamation projects have remained a key component of North Korea’s “nature re-making” initiative. Recent satellite imagery shows that these projects continue to expand as part of the country’s strategic goal of increasing grain production—the first of 12 major tasks being undertaken for national economic development.

North Korea began its tideland reclamation efforts in 1958 with a project at Pidan Island, at the mouth of the Yalu River. In April 1963, founding leader Kim Il Sung issued a directive endorsing the remaking of nature. Then in October 1981, the Sixth Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea adopted four “great nature-remaking projects” at its fourth plenary session, including the reclamation of 300,000 hectares of tideland.

Through these projects, sections of coastal tideland are filled in and used for salt production, aquaculture and agriculture.

Recent satellite imagery from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel 2-B and 2-C satellites shows that dike construction and soil development are underway in several parts of the Yellow Sea tidelands in North Pyongan province.

North Korea’s tideland reclamation projects have caused immediately noticeable changes to the regional geography.

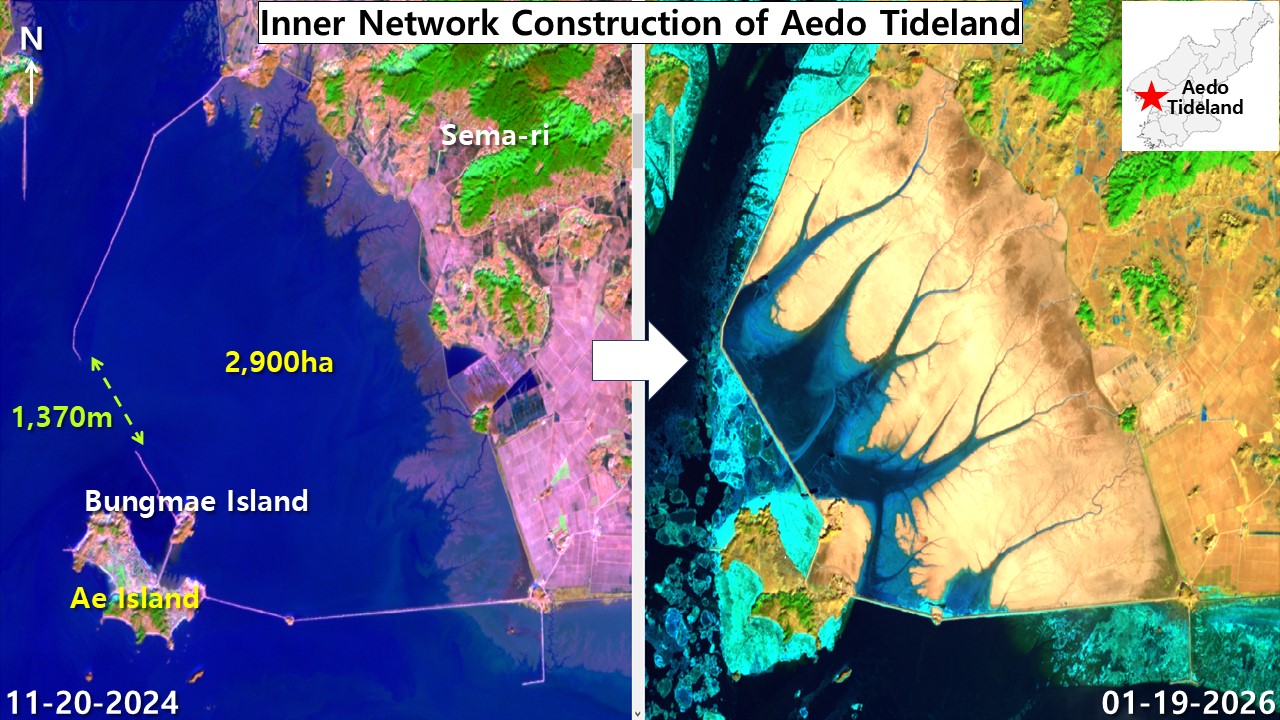

Tideland reclamation at Ae Island

A major effort to reclaim shallow tidelands on the Yellow Sea is underway off the coast of Chongju, a city in North Pyongan province. Construction is complete on a dike, begun in late 2023, between Ae Island and the mainland. Now work is underway on the land inside the dike to establish drainage and irrigation networks and improve the soil. (Sentinel-2B/2C)

A major effort to reclaim shallow tidelands on the Yellow Sea is underway off the coast of Chongju, a city in North Pyongan province. Construction is complete on a dike, begun in late 2023, between Ae Island and the mainland. Now work is underway on the land inside the dike to establish drainage and irrigation networks and improve the soil. (Sentinel-2B/2C)

A dike running for dozens of miles between Ae Island and the nearby shoreline has been built on the wide expanse of mudflats off the coast of Chongju, a city in North Pyongan province. The completion of the dike separated the land inside from the ocean beyond. Since then, work has focused on preparing the enclosed land by creating a drainage system, removing salinity, setting up irrigation equipment and installing ditches and pumps.

“A belt road has been constructed along the coastal dike at Chongju, and thousands of hectares of tideland have been reclaimed,” North Korea’s state-run Rodong Sinmun said in a triumphant report on the reclamation project on Jan. 15. This report underscores the authorities’ determination to connect tideland reclamation with the expansion of arable land and, consequently, grain production.

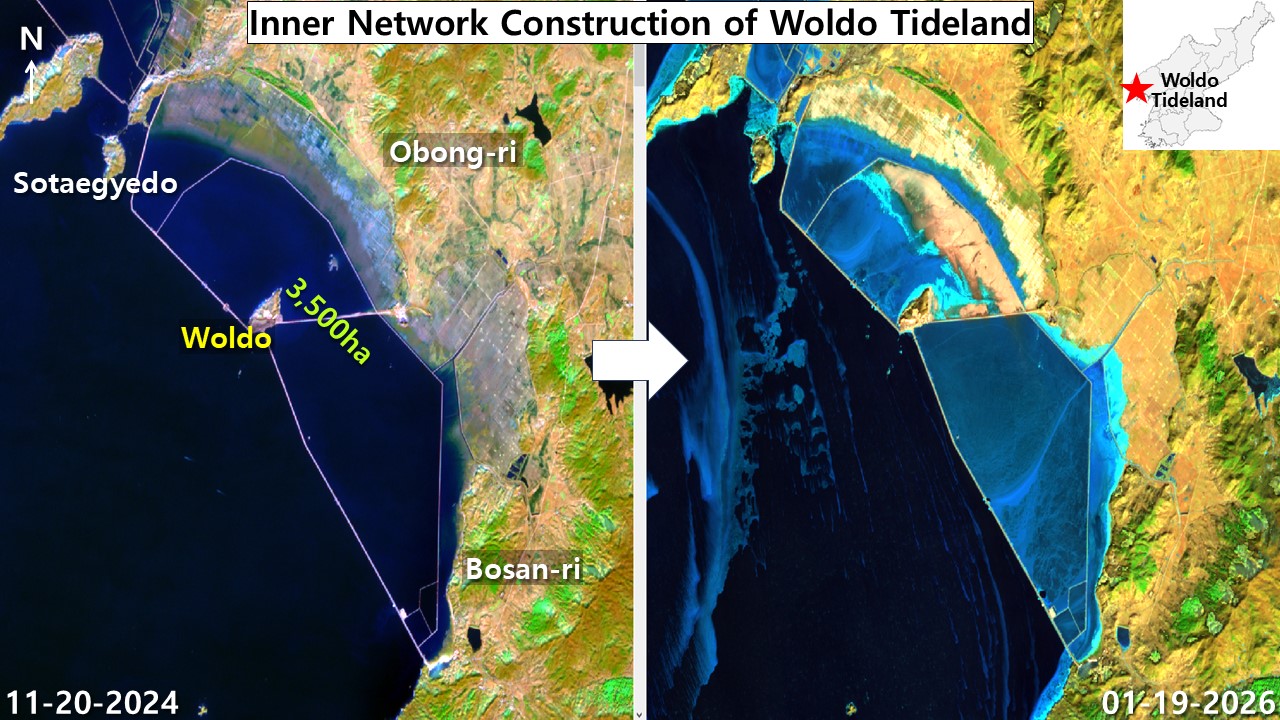

Tideland reclamation at Wol Island

A dike has been erected around mudflats to the north and south of Wol Island (off the coast of Cholsan county in North Pyongan province). The area inside the dike is currently being developed with the goal of producing 3,500 hectares of reclaimed land. (Sentinel-2B/2C)

A dike has been erected around mudflats to the north and south of Wol Island (off the coast of Cholsan county in North Pyongan province). The area inside the dike is currently being developed with the goal of producing 3,500 hectares of reclaimed land. (Sentinel-2B/2C)

The tideland reclamation project at Wol, an island in the Jangsong district of Cholsan county, North Pyongan province, began in June 2019 under government leadership. As part of this project, the expansive mudflats were blocked off with a dike and other structures to keep seawater out. This project has been underway for several years now, and recent Sentinel satellite images show the completed dike and the land inside under development.

The large-scale mudflat development project near Wol Island started with the construction of the dike in June 2019. After the dike was complete, engineers shifted their focus to converting the enclosed land into farmland by building floodgates, canals, irrigation facilities and other necessary infrastructure.

As part of its “great nature-remaking projects,” North Korea’s ambitious tideland reclamation projects involve walling in the targeted land, reducing salinity, adjusting drainage and preparing the ground—all with the goal of turning tideland into arable soil.

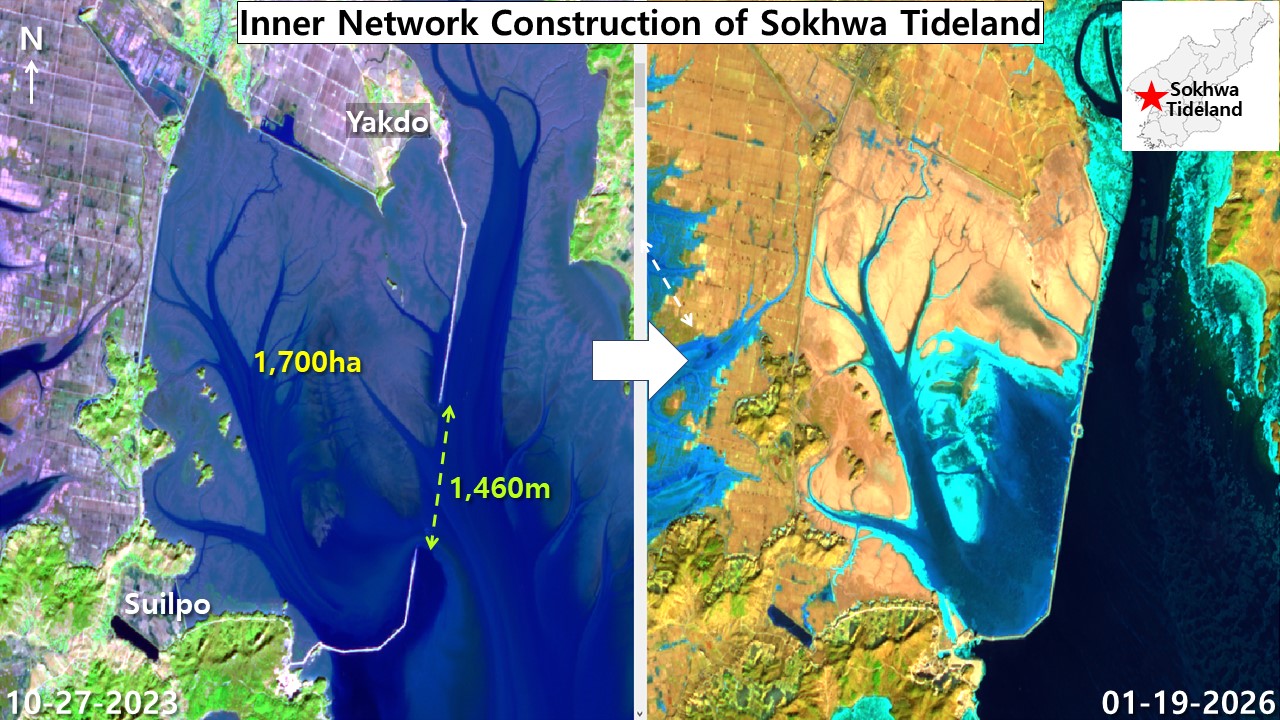

Sokhwa tideland reclamation

North Korea erected a six-kilometer dike along the coast in Sonchon county and is currently developing around 1,700 hectares of land reclaimed from the ocean. (Sentinel-2B/2C)

North Korea erected a six-kilometer dike along the coast in Sonchon county and is currently developing around 1,700 hectares of land reclaimed from the ocean. (Sentinel-2B/2C)

North Korea has filled in mudflats on the coast of Sonchon county, North Pyongan province, as part of the Sokhwa tideland reclamation project. The state-run Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) recently reported that “military engineers have completed the primary reclamation work by erecting dikes around the mudflats to keep out seawater.”

As this report indicates, the Sokhwa tideland reclamation project began with the construction of a dike surrounding the mudflats off the coast of Sonchon county. This work aims to first fence off the shallow mudflats and then fill in the interior and develop the reclaimed land for productive uses.

Tideland reclamation of this kind is one of the “great nature re-making projects” organized by the North Korean state. Reclamation consists of three stages: construction of a dike, installation of floodgates and other necessary facilities, and conversion to arable land.

At the Sokhwa tideland reclamation project, the primary stage of work (building a dike to keep out seawater) is now complete. The project appears to have progressed to the farmland preparation phase, which involves reducing salinity levels and installing drainage and irrigation facilities—in keeping with the three basic stages outlined above.

North Korea’s tideland reclamation: challenges and side effects

While North Korea is seeking to create more farmland by reclaiming mudflats and tidelands, such efforts are believed to be constrained by soil quality and agricultural productivity. Since soil derived from mudflats and tidelands retains the impact of the seawater that once covered it, that soil is likely to remain saline even after a dike is built, and additional measures are required to reduce saltiness. That lingering salinity presents challenges for cultivation, experts observe. What that means is that while land reclamation may increase North Korea’s arable land, it does not immediately translate into a proportional increase in productivity.

Furthermore, mudflats are both a marine habitat and a natural environment providing a range of ecological benefits, such as removing pollutants and serving as a conduit for tidal waters. Efforts to reclaim those mudflats and convert them to farmland carry the risk of compromising the functions of the marine ecosystem and the basis for fishery resources. International researchers say that mudflats are of crucial environmental value in terms of absorbing carbon and maintaining biodiversity and voice concerns that eliminating mudflats may compromise these ecological functions.

Considerable work is required before tideland can be reclaimed and used for agriculture: a dike must be built, drainage and irrigation facilities must be installed, and soil must be improved. And all those facilities require continuing maintenance. One cannot overlook the fact that increasing the agricultural productivity of land reclaimed from the ocean is both costly and time-consuming.

Like any development project, tideland reclamation involves practical difficulties: it is labor-intensive and requires high maintenance. For the reclaimed land to become arable, basic agricultural infrastructure—including appropriate machinery, fertilizer and irrigation—is essential. Given North Korea’s inadequate facilities and resource shortages, therefore, it is unlikely that reclaiming tideland will immediately lead to increased agricultural productivity.