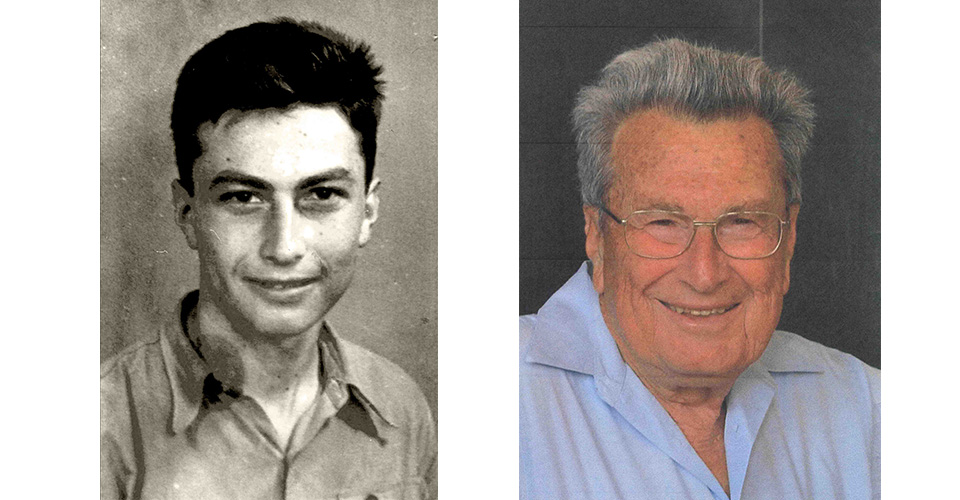

Prof. Igal Talmi, a leading pioneer of Israeli science and a founder of nuclear physics research in Israel, passed away today, just days after his 101st birthday. Less than two weeks ago, his wife of 77 years, Chana Talmi (née Kivelewitz), passed away at the age of 100.

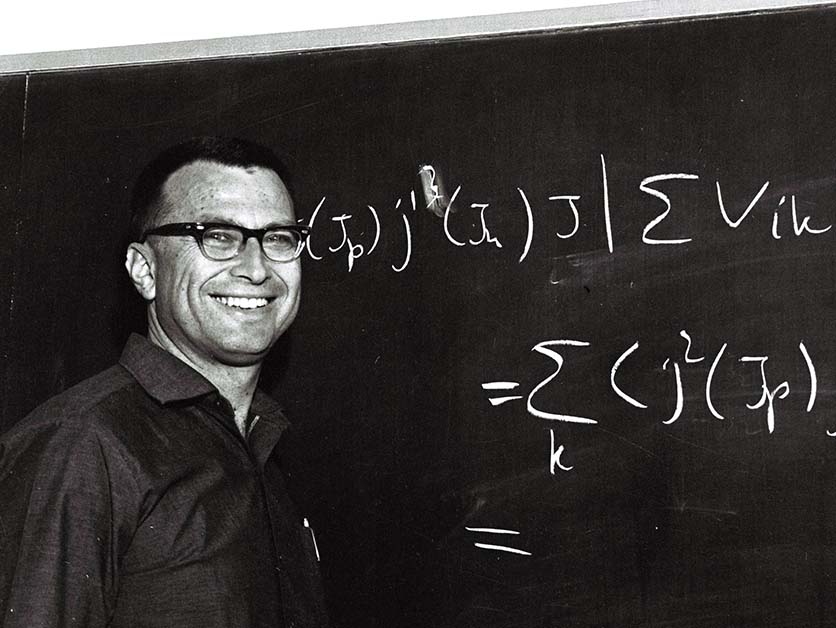

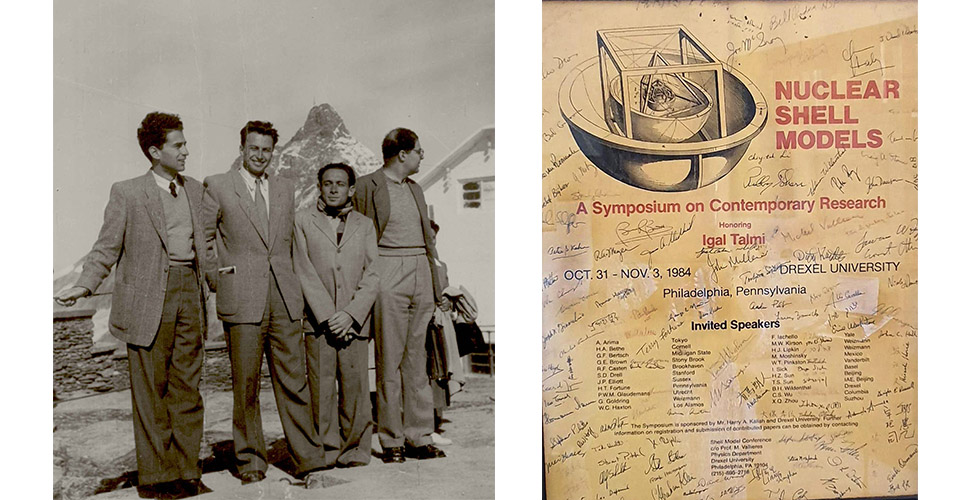

Talmi was among those who deciphered the structure of the atomic nucleus, and several of the theories and computational methods he developed are still in use today. During his doctoral research in Switzerland, under the supervision of the Nobel Prize laureate Prof. Wolfgang Pauli, he developed a method that substantially simplified calculations in the nuclear shell model. After completing his PhD in 1951, he conducted postdoctoral research at Princeton University with another Nobel laureate, Prof. Eugene Wigner.

Upon returning to Israel in 1954, Talmi joined the Weizmann Institute of Science and was among the founders of Israel’s first nuclear physics department. In 1963, together with Prof. Amos de-Shalit – also a pioneer of Israeli nuclear physics – he published the book Nuclear Shell Theory, which became an instant classic. In 1993, Talmi published another book on the subject, Simple Models of Complex Nuclei: The Shell Model and Interacting Boson Model.

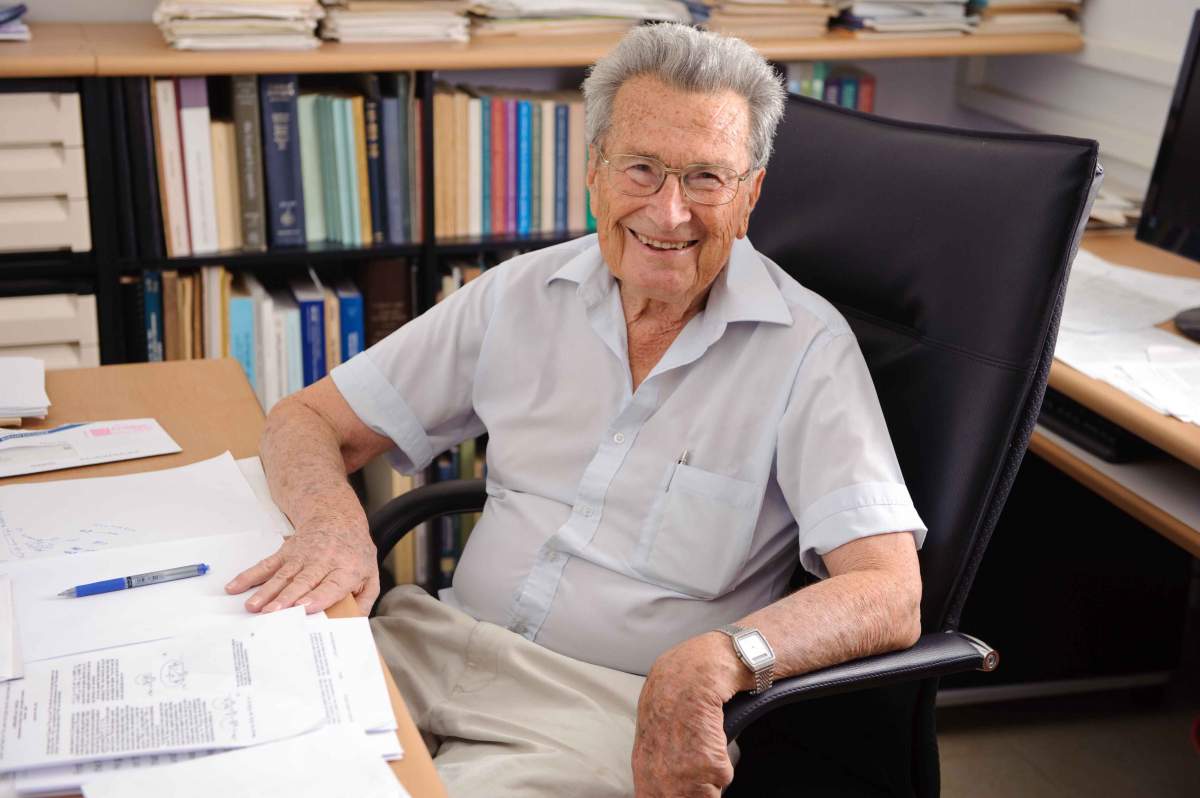

Talmi received wide recognition in Israel and abroad for his contributions to nuclear physics. He served as a visiting professor at MIT, Yale, Princeton and other leading universities around the world. Until his retirement in 1995, he was a professor at Weizmann and over the years served as head of the Nuclear Physics Department, dean of the Faculty of Physics and chair of the Institute’s Council of Professors. He was also a member of the Israel Atomic Energy Commission and since 1963 a member of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. His numerous honors included the Weizmann Prize (1962), the Israel Prize in the Exact Sciences (1965), the Rothschild Prize (1971), the Hans Bethe Prize of the American Physical Society (2000) and the EMET Prize (2003).

A butterfly hunter in the Jezreel Valley

In 1925, Igal Talmi, then one year old, made aliya to Eretz Israel from Ukraine with his parents, Moshe and Leah Talmi (formerly Smilanski), and his ten-year-old sister, Tehia. His parents, both Hebrew teachers, left Kiev after the Soviet authorities shut down Hebrew-language schools, and traveled by ship from Odessa to Jaffa. The family settled in the moshav Kfar Yehezkel, in the Jezreel Valley. There, at the foot of Mount Gilboa, Igal grew up and attended the local school, which was headed by his father.

A close childhood friend introduced Igal to the world of butterflies. During school holidays, they would hike in the countryside, hunting butterflies and studying plants, earning the nickname “butterfly hunters” from friends who valued only agricultural labor.

Talmi initially dreamed of studying biology, but first he needed to complete his secondary education. During World War II, with Haifa under bombardment, his parents decided he would study at home rather than attend school in Tel Aviv. While studying independently, Talmi came across an old physics textbook that described how natural phenomena, such as falling bodies, could be calculated. This discovery sparked his imagination, and he gradually abandoned the idea of biology in favor of physics. His self-directed studies, however, were uneven: He focused on subjects that interested him and neglected others. Eventually, despite concerns for his safety, his parents sent him to live with friends in Tel Aviv, where he studied at the Herzliya Gymnasium.

Upon graduating in 1942, Talmi volunteered for the Palmach (“strike companies”), a brigade within the Haganah, the underground military force of the Jewish community during the British Mandate. Palmach members lived on kibbutzim, working for their keep while undergoing military training. After several months, Talmi was released for health reasons – a scare that later proved unfounded – and began studying physics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

“”Talmi was among those who deciphered the structure of the atomic nucleus, and several of the theories and computational methods he developed are still in use today”

There he met fellow students, including de-Shalit, Gvirol Goldring and Gideon Yekutieli, who would later become founders of the Nuclear Physics Department at Weizmann. Their lecturer was the physicist Prof. Yoel (Giulio) Racah, who had made aliya to escape the racist laws in fascist Italy.

When Talmi completed his MSc studies, Racah offered him a position as a teaching assistant and PhD student, but Talmi set his sights on Europe, specifically the lab of Prof. Pauli at ETH Zurich. In 1947, however, with the outbreak of hostilities in Eretz Israel, he postponed his departure.

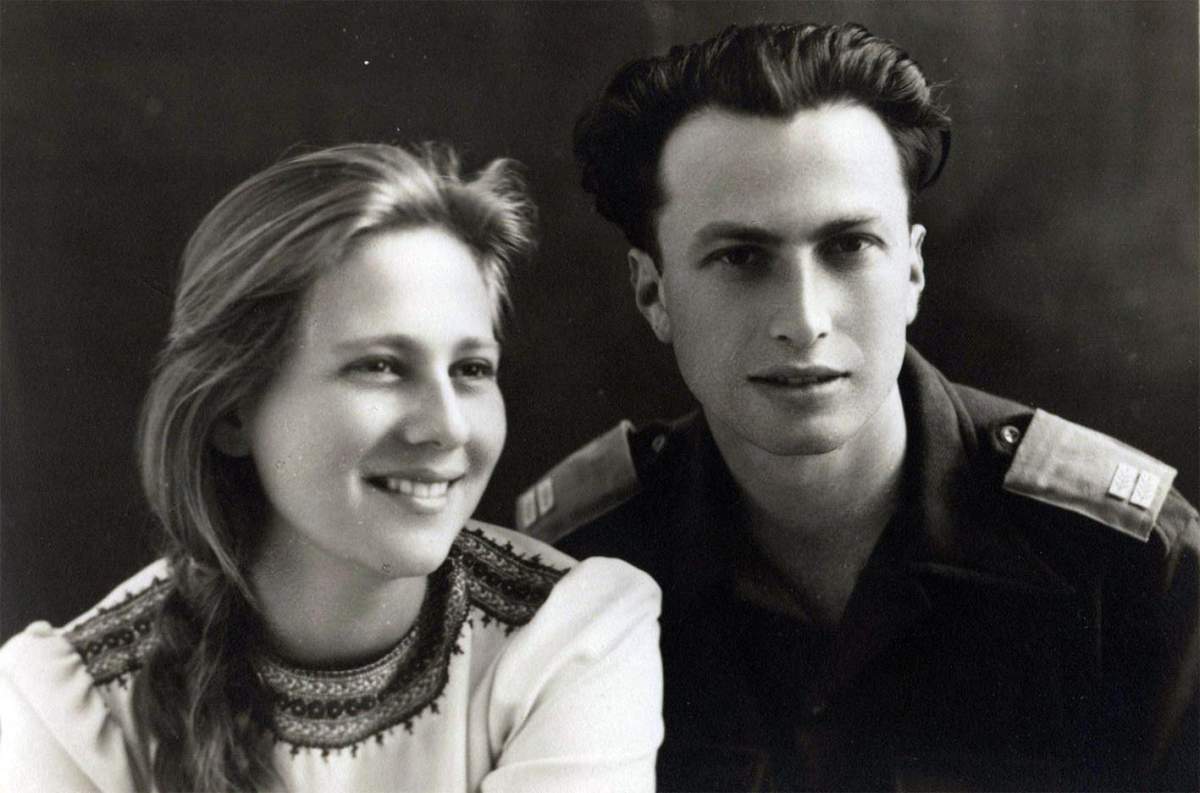

During the War of Independence, Talmi fought in combat units and initially refused offers to join Hemed, the new science corps. After repeated attempts to persuade him, including through his then girlfriend (and future wife) Chana, he was eventually ordered to report to Hemed’s base in Rehovot. Talmi later recalled traveling through the dangerous Burma Road in an army jeep, armed with a single grenade.

Hemed became the nucleus of scientific research in the new state. Talmi and his colleagues recognized how far Israeli physics lagged behind developments in Europe and the United States and believed that studying abroad was essential to closing the gap. These views reached senior figures close to David Ben-Gurion, who ultimately approved sending a small group of young physicists overseas at the state’s expense. Talmi and his wife Chana traveled to Switzerland, where he took up his delayed doctoral studies under Pauli.

Upon their return to Israel, the group of Hemed “alumni” joined the pioneering generation of Israeli science and played a major role in shaping the Weizmann Institute of Science. Rejecting the hierarchical European model, they treated students and junior researchers as partners, encouraging them to pursue independent research interests and laying the foundations for Israel’s innovative scientific culture.

Talmi’s love of nature never faded. In later decades, he became an avid birdwatcher, a hobby he took up during hikes with his son.

Chana and Igal Talmi are survived by two children, seven grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. Their son, Prof. Yoav Talmi, is a specialist in ear, nose and throat medicine and head and neck surgery; their daughter, Prof. Tamar Dayan, is a professor of zoology at Tel Aviv University and the founding chair of the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History.