Finally, while artificial wombs have already successfully grown sheep, estimates vary on when we’ll be able to grow humans — though some say it may only be a decade from now. This will undoubtedly be transformative for would-be parents who currently have to rely on surrogates. But what about a nation in demographic collapse? What sort of moral landscape would govern states that want to grow children? Or dictators who want to grow cannon fodder for their armies?

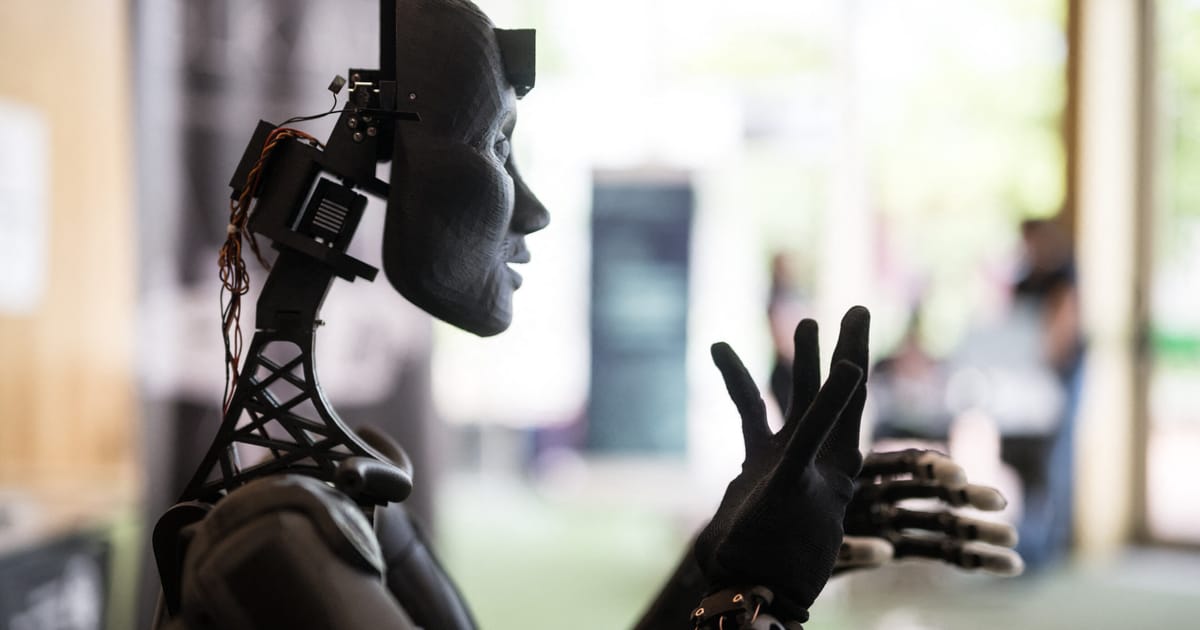

Moreover, we may not even be growing humans as we know them. Mind-machine integration has already begun in earnest, and brain-computer interfaces are no longer confined to science fiction. Most prominently, Neuralink Corp — one of Musk’s ventures — is actively developing and testing implantable devices that could allow humans to directly control computers or prosthetics with their brains. If successful, this means major brain damage could be curable — but we could also be looking at remotely monitored and controlled humans.

If our future on this planet seems like a sci-fi film though, space is even more so. The burgeoning space industry is currently worth over $500 billion annually and is projected to reach $1.8 trillion by 2035. But while the 2020 Artemis Accords seek to regulate life and business in space, they have yet to be signed by China (the world’s second-largest spacefaring nation), Russia or India. And how does Musk’s ambitions for SpaceX to build a sustainable colony on Mars — with its own governance — fit into all this?

Governments need to start preparing and reforming. Keeping up with the evolution of all this technological change, let alone channeling it, is enormously challenging, particularly when very few public sector leaders are even really aware of these critical emerging technologies.

Currently, such discussions in government are typically confined to a few niche teams and backroom wonks. Thus, part of the solution is talent and capability. Apolitical’s research shows that globally, only 65 percent of public servants have received any guidance on AI, and 85 percent haven’t received any training. This AI knowledge gap has to be filled.

Governments also need to stand back and examine the bigger picture. The public sector and its institutions need up-skilling not only in AI but in all critical future technologies.

And, crucially, our institutions need reform as well. This requires real leadership, but it is possible: We’re in a time of crisis, and it is in times of crisis that real change can be achieved.

Collectively, emerging technologies are creating an unstable world, where we don’t clearly understand what national security looks like. Reform will require imagination and energy, as well as unpopular decisions. But the first duty of any government is to protect its population. And when our leaders confront these emerging technologies — which they must — it will be clear that they lie at the heart of national security, for better or worse.