For the present-day society, the communal flat (in colloquial speech during the Soviet period called ‘kommunalka’ or ‘kommunalnyk’ from the Russian abbreviation) is probably associated only with the official video of a song by Latvian music band Remix from the distant 1980s that could remind us of some striking typical scenes from everyday life of that time. Should we regard them today as exhibits of a virtual history museum? In Latvia since the release of the song, The Communal Blues, there has been a change in the political system and economy, the real estate market has come back to life and the daily worries are completely different from the ones that people faced in the era of communal flats. Latvia’s society has also changed: its composition and values as well as our consumption habits and demands have altered.

Dependence on the fluctuation of housing loan rates is only one reason why a part of present-day society would eagerly believe that the housing issue can be efficiently resolved through state intervention. Viewed from a distance, many things seem different, quite unlike how their contemporaries perceived the events that we call history. Memory is a capricious and opinionated lady, it may remember and forget things at her own discretion and, furthermore, is affected by everything that constitutes the person’s experience, from their childhood to yesterday. Thus, it is worthwhile to look into the past, which is separated from the present day by slightly more than one generation, to take stock of the differences and similarities.

“Kommunalnyk! The wonderful enforced intimacy. Smells and noises, celebrations and brawls, international love and inter-ethnic hatred… The passions! And all this happening in a few square meters of housing…” – this is how actor Vilis Daudziņš describes the essence of the communal flat. The communal flat was not only a part of daily life for many inhabitants of the Soviet Union (USSR); it became a typical phenomenon of an era with an existential meaning. It explains why historian Juri Slezkine uses the concept of the communal flat as a metaphor for the Soviet regime to describe its inter-ethnic policies, which served as one of the causes of the collapse of the state. How did this phenomenon emerge and function?

All for the people, all for their well-being

In Soviet socialism, the path to having a home of your own was long and bumpy. The socialist state was obliged to guarantee its citizens a chance to get a job, home, education as well as medical and social care for free or for a relatively small fee. A precondition for meeting these obligations was the existence of a state-organized and controlled economy and politics; in practice, however, much more was needed: it was necessary to create a new order of life and a new type of human, the so-called Soviet man, who would voluntarily develop and follow a lifestyle compatible with the ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU).

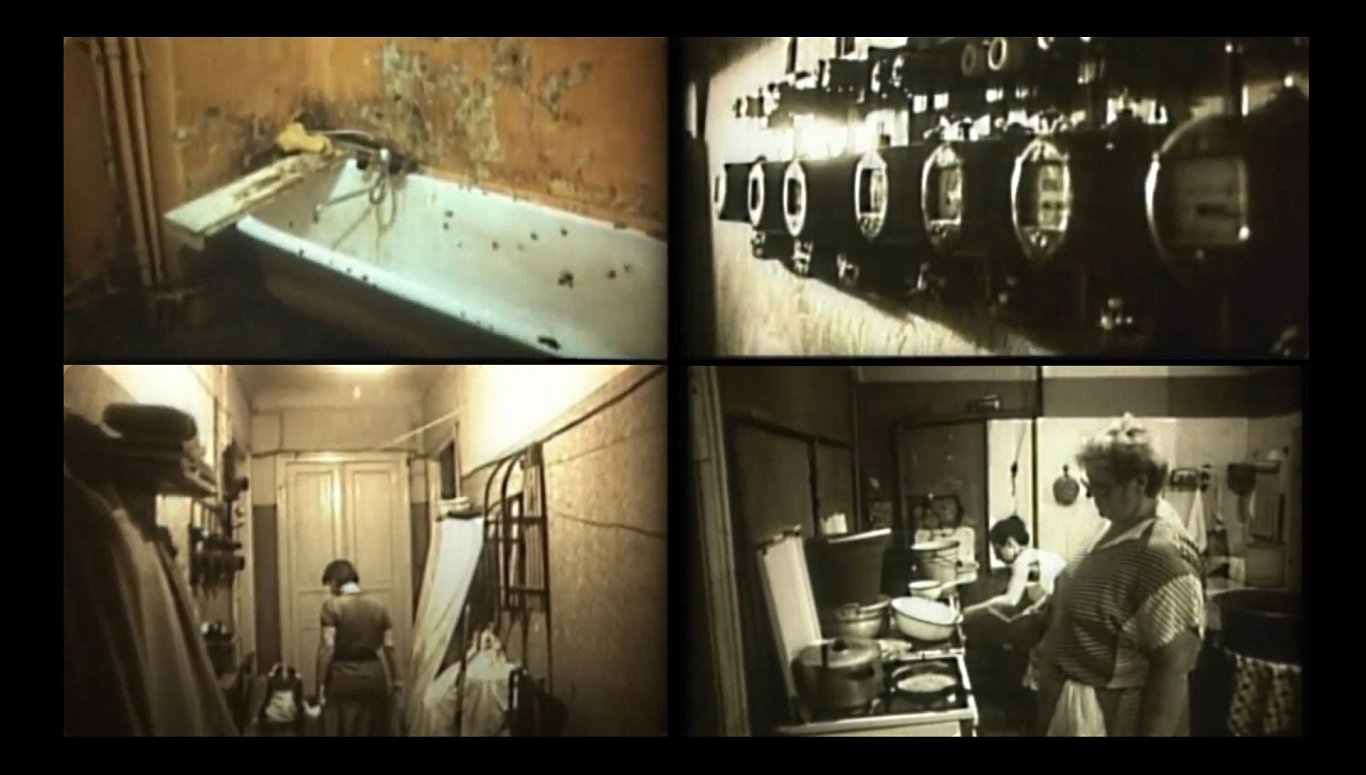

Photo: Kadrs no filmas “Trīs dienas pārdomām”

An essential part of such a lifestyle was the restriction and control of one’s personal privacy that was carried out not only by the Soviet state itself but also by one’s contemporaries; the communal flat was one of the tools of such control throughout the existence of the Soviet regime. During the Stalinism period, enforced communal living facilitated mutual distrust and denunciations among neighbors. With the passage of time, it developed into a habit; the neighbors sharing a flat kept an eye on each other even without a special political incentive, but it did not make the daily domestic control less depressive: the communal flat was one of the most effective tools for the infringement of a person’s private life.

Communal flats emerged in the Soviet Union in the 1920s in the context of the class struggle waged by the communists that required divesting the bourgeoisie of their properties and distributing them among others in the name of quasi-social equality. It entailed lodging several other households in a home previously owned by one family. An even more important factor was mass-scale migration or rather fleeing by rural population to towns as a result of the civil war and the subsequent enforced collectivization, bringing about a multiple increase of the urban population.

In the USSR as of the 1920s the communal flat was regarded as a tool for shaping a new “socialized” way of life that made people’s daily lives easier to control. In the communal flat, all your neighbors knew how you spent your spare time at home, whom you met etc. Thus, the communal flat was something more than a temporary solution to urban overcrowding: in the Soviet state, it also carried a political and ideological message.

According to the calculations of the State Planning Committee of the Latvian SSR, in the first twenty years after the end of the Second World War, the rapid population growth was due to the influx of immigrants. A significant proportion of them were demobilized from the Soviet army, as well as workers from industrial enterprises in Riga and other major cities. In the early 1950s, and since 1960, mechanical population growth exceeded natural growth. The population of Riga grew the fastest: from 261,000 in September 1945 to 656,000 in January 1965. Thus, it was migration that became the main cause of the permanent housing shortage that made communal housing an inevitable part of life in Soviet Latvia.

At the end of the Second World War along with the restoration of the Soviet occupation regime, a rapid influx of inhabitants from other parts of the Soviet Union into Latvia began: by 1959, their number exceeded 400 thousand and continued to grow in the subsequent decades, majority of the newcomers settling down in Riga.

In 1944, along with the return of Soviet rule, the houses in the center of Riga saw the comeback of the era of communal flats that had started already in 1940-1941. This time the communal flats were established both in those apartments whose former owners had emigrated, had been arrested or deported by the Soviet regime, as well as in those still inhabited by the pre-war residents who had to put up with the new neighbors.

Thus, in occupied Latvia, the housing issue was closely related to the ethnic one and served as a cause for inter-ethnic conflicts: “Most often such conflicts arose in flats where the owners were deprived of some of their own rooms and forced to make space [for the newcomers]. Many of them had happily resided in their flats for decades, had worked to save money to buy and furnish them, [..] and there suddenly comes somebody who out of ignorance ruins and breaks [things],” writes Andris Kolbergs in the magazine “Karogs” in 1985.

The communal flat meant that “strange, unfamiliar people have come close to your life – so close as to even poke their noses into your pot. Nothing like that was known in pre-war Riga and the phrase “communal flat” could not have been found in any dictionary then.”

In the 1980s writer Andris Kolbergs colorfully depicted such conflicts: in his detective novel a retired Soviet officer is amazed about the “bourgeois apartment” in which he had settled down. He says: “What jerks, they do not know how to build houses! The ceiling is so high, who can heat such a flat in winter?”, whereas the former owner is forced to helplessly stand by as the new resident wreaks havoc in his flat: “Just look what this derevnya [Russian: “the sticks”] has pulled off again! They are scrubbing the parquet with a brush and water – it is ruined now!”

Evidence about life in communal households both in the post-war period and in the early 1980s has been preserved in the contemporaries’ memoirs and diaries, revealing depressive daily experiences. Relations among neighbors were often based on the survival of the fittest principle, them fighting for the chance to use the shared facilities (kitchen, bathroom, WC) and telephone and resorting to insolence and blackmail, such as threats to file a claim with the militia to get the upper hand. Household conflicts, the so-called communal flat wars, were an ever-present element in the lives of the residents of such flats, however, the Soviet propaganda pretended not to see it or penned stories about friendly social life in communal flats where neighbors are always ready to help each other, as shown in the films of that time.

Photo: Kadrs no filmas “Trīs dienas pārdomām”

The communal flats did not disappear even in the later period although in the late 1950s construction of standard apartment buildings was launched in the USSR cities with an expectation that the constant housing shortage would be eliminated in the subsequent 10-12 years. Due to various reasons, it did not happen and in 1986 CPSU set a new deadline for the resolution of the housing problem: this time every family was to have a home of its own by the year 2000. The state-run flat construction program Flat-2000 was extensively examined by popular magazine Zvaigzne in seven articles published in 1987 that are openly skeptical about the feasibility of the program due to the steadily growing economic problems and regard support for the construction of private houses as a more hopeful solution. However, the speedy collapse of the Soviet regime in the subsequent years essentially changed the rules of the game in construction and housing policy in Latvia.

A long way to go to square meters of one’s own

An opportunity to have a home of one’s own is one of a human being’s basic needs. By declaring the state’s responsibility for access to housing for its inhabitants, the Soviet rule obtained broad opportunities to control their living conditions including granting the right to use a flat. A Soviet citizen could legally inhabit a dwelling only if they were registered there, i.e., received a document certifying their right to reside within the limits of a specific administrative unit and on this basis received a warrant for acquiring a housing unit.

The next threshold on the path to a home of one’s own was the procedure of granting flats, which was affected by the person’s belonging to a privileged social group, which would be given priority in the distribution of flats. The state also set a minimum floor-space per person that in turn gave one the right to claim a flat on a ‘first come, first served’ basis. The relevant quotas were regularly revised and aligned with the flat construction standards that since the 1960s were dominated by two-room flats with a standard floor-space of 36 square meters that was envisaged for a family of four. However, if the family was not large enough and thus the floor space per person in such a standard flat would exceed 4 or 5 square meters, the family could not even register in the flat queue where waiting time was 10 or even 20 years.

The housing market was not legal in the Soviet Union, it was substituted by the distribution of floor-space. There were two paths to acquiring the right to use a flat in the Latvian SSR: first, a person could receive it from the municipality they lived in or an enterprise they worked in; second, a person could join a flat construction co-operative society where they had to pay 40% of the value of the flat right upon receiving it, while the remaining 60% qualified as a state loan that had to be repaid in 10-15 years after the receipt of the flat.

Municipal authorities and enterprises organized construction of apartment buildings and flat queues of their own parallel to those of the state. Flat cooperative societies were established under the umbrella of such enterprises; membership in such societies was also subjected to the minimum floor-space quotas. For those who did not belong to the privileged part of society (officers of the Soviet army, veterans of the Great Patriotic War [i.e., the Second World War], members of artistic societies, professional scientists) or were unable to build an individual residential house, the flat co-operative society was the only way to acquire a dwelling without long waiting in queue. It required massive financial investment and the strictly limited individual earning possibilities in the Soviet state considerably restricted the range of potential owners of co-operative flats.

Settling for the chance to receive the right to use a flat on a ‘first come, first served’ basis, one had to reckon that they would probably wait in queue for years. It was one of the gravest daily problems in the Latvian SSR and no solution could be seen in the near future. Thus, in the crime film Raspberry Wine (1984) shot at Riga Film Studio, one of the possible motives for murder was the need to get money for an installment to buy a cooperative flat.

The suspect, engineer Vilis Zīraps explains the situation to the militia major: “I have been waiting in a flat queue for five years already. It is hopeless… And there suddenly – [a chance to buy] a co-operative flat! I have to pay the installment on Monday and the flat will be mine. What I have now is one room in a kommunalka where I live with my wife, our two daughters, and my mother-in-law. And there suddenly [appears a chance to have] four isolated rooms! The first installment is six thousand, I was short of two. You understand me: if I do not get the money by Monday, somebody else will take [the flat].”

At that time a professional with the highest technical education received a monthly salary of 120-140 roubles, thus 6000 roubles was a large amount that was not easy to collect.

The verisimilitude of the film episode is affirmed by a memory sketch entitled Communal Flat – an Undeserved Punishment by Franks Gordons, a former reporter for newspaper Rīgas Balss that he published in the newspaper of Latvian exiles in the USA Laiks in 1978, after emigrating to Israel.

Gordons recalls his twenty-three years long experience in a communal flat in a house in the center of Riga where “the four of us lived – me, my wife and our two children – in one room of 12 square meters while the kitchen was shared by four ladies (four families resided in one five-room flat)”.

As the number of residents in a communal flat changed, in case some of them passed away or moved elsewhere, the living conditions of the other families sharing the flat could temporarily improve; however, usually the neighbors used the opportunity to register in the newly vacant floor-space a relative of theirs who was looking for a dwelling in Riga or some other town in the Latvian SSR.

Housing shortage was especially acute in industrial centers in the urbanized regions of the USSR, and the Latvian SSR was one of them. In the mid-1980s, 70% of Latvia’s population lived in cities and approximately half of them resided in Riga, where in 1987 the population already exceeded 900 thousand. No flat construction measures were sufficient to absorb a population as high as that. Gunārs Melbergs, architect and urban planner acknowledged in 1989: “Currently there are 77 thousand families, i.e., more than 200 thousand people registered in the flat queue in Riga and, considering the preconditions one has to meet to be registered in the flat queue in Riga, one must admit that the living conditions of these people are tragic, to put it mildly.” During the Soviet occupation, the population of Latvia’s capital steadily increased due to mechanical growth, mostly through staffing up factories, the Soviet Army officers and the military personnel of the Baltic Military District.

The discreet problems of the deficit economy

Housing shortage affected all fields of life and perpetuated inter-ethnic tensions in society between the ‘locals’ and the ‘migrants’ who, due to the forced industrial development, as of the 1960s had better chances of getting an individual flat in Latvia. Information about it quickly spread in broad circles and it naturally encouraged the growth of migration. In 1991 there were 13,700 communal flats in Riga housing approximately 90 thousand people, i.e., almost one out of ten residents of the capital.

Sociologists did admit the negative impact of the constant housing shortage on birth rate and the overall population changes in Latvia. However, under the conditions of deficit, getting an individual flat did not resolve all of one’s problems, as the person continued to be affected by the shortage of floor space.

Photo: Kadri no dokumentālās filmas “Kas dzīvo komunalkā?”

The situation is aptly illustrated by Aivars Tarvids in his story Smoke (1983): “Indeed, Andrejs pondered, there are people who somehow get along with their little engineer’s salary, trying hard to buy cheap chicken to feed their children, keeping repaying the debt for their rusty Zhiguli car, waiting in flat queue for years – correction – decades and regularly paying rent to a house-owner. When the family finally happily moves into [a flat consisting of] two rooms with paper-thin walls, a tiny lobby and a doll’s kitchen and when the new bird cage-like furniture bought for painfully saved money is assembled, they are shocked to find out that the children have already grown up, the daughter-in-law is pregnant or there is a son-in-law from countryside staying with them, the young ones have nowhere [else] to live in the city, thus they all have to crowd together, do their laundry and cooking according to schedule and at night, after the TV evening program is over, put down their foam bunks and wait for better times.”

The flat issue that journalists and writers, such as Mikhail Bulgakov and Mikhail Zoshchenko, bitterly ironized about already before the Second World War, remained unsolved in the Soviet Union.

Although sociologists of Soviet Latvia strongly emphasized that the mechanical growth of the population “for the most part was not a result of planned re-distribution of population and labor resources, but rather was mainly caused by unorganized migration”, a sociological study conducted in 1972-1973 about the motivation for the migration of working-age people to Latvian towns revealed that one of the main causes for the steady influx of migrants from Russia, Belarus and Ukraine was their hope to receive individual flats here. A part of those who were disappointed in their hopes and had to live in a factory workers’ dormitory for a long time, moved elsewhere to look for a new start and job. Acknowledging that in Latvia “demand for labor force constantly exceeds the offer”, one could not avoid reaching the conclusion, which the official publications held back: such demand did not emerge spontaneously but was associated with the Soviet economic development plans that envisaged ceaselessly building ever new factories in Latvia. Thus, the constant housing shortage and the consequential perpetuation of the communal flats system in Latvia was a result of the economic and demographic policies pursued by the Soviet regime in Latvia.

The communal flat as a problem of daily life was featured in several literary works, for example in the stories by the representatives of the 1980s New Wave of the Latvian prose, such as Rudīte Kalpiņa, Andra Neiburga, and Eva Rubene – however, on the whole, it was regarded as a marginal and politically unacceptable topic. It was still inadvisable to raise it in journalism: until as late as the end of the 1980s, due to political reasons, the censorship repeatedly banned the publication of the article Man behind the Door by writer and editor Ēvalds Vilks (1923–1976), which had been written already in 1968 and focused on housing shortage in Riga caused by the planned forced industrial development.

All this time, the mechanical growth of the population in Riga and the other largest Latvian cities continued unrestricted. It was only in February 1989, when the Soviet Union had only a couple of years left to exist, that the Latvian SSR Council of Ministers adopted a decision to stop the mechanical growth of the population and regulate migration processes.

Despite its name that suggested co-operation among the community of flat residents in the name of a common good that the Soviet propaganda loved to underline, in fact the practice of communal flats in most cases drew a wedge between their residents. Cohabitation in a communal flat demanded not only sensitivity but also tenacity:

“It is such a burden when all of your personal life is exposed, open to strangers’ eyes and ears. Some [neighbors] may have guests and what if there is somebody else [among the neighbors] who secretly earns on the side by giving private mathematics lessons or sewing dresses and thus is receiving customers?”

Trespassing of the boundaries of private space in daily interrelations was inevitable and caused psychological tension even in cases when the neighbors of the flat did not particularly dislike each other. Dissociation from each other in order to safeguard what little there was left of one’s privacy turned residents of the communal flat into strangers who often regarded each other with hostility. Along with some other features of daily life, such as the favors (‘blat’) i.e., the corrupt system and the deficit of various commodities (from food products to furniture and cars), the communal flat grew into a symbol of the Soviet regime that, like the ghost of communism once invoked by Karl Marx, roamed over the Soviet Union as a living reminded of the CPSU aspirations to create a new Soviet man.

This article is part of the series “The Most Popular Myths in the 20th -21st Century History of Latvia” published on public media portal LSM.lv. The publication has been prepared withing the framework of the State Research Programme project “Navigating the Latvian History of the 20th-21st Century: Social Morphogenesis, Legacy and Challenges” (No. VPP-IZM-Vēsture-2023/1-0003).

Bibliography

Bleiere, Daina (atb. red.) (2022). 20. gadsimta Latvijas vēsture IV (1944/1945–1964). Rīga: LU Akadēmiskais apgāds.

Brambe, Rita un Zvidriņš, Pēteris (1984). Iedzīvotāji. No: Jērāns, Pēteris (galv. red.). Latvijas Padomju enciklopēdija. 5-2. sējums: Latvijas PSR. Rīga: Galvenā enciklopēdiju redakcija, 116.–128. lpp.

Daudziņa, Zane (2024). Bērnudienas Komunālijā. Rīga: Zvaigzne ABC.

Dzīvokļu politika (1987). No: Jērāns, Pēteris (galv. red.). Politiskā enciklopēdija. Rīga: galvenā enciklopēdiju redakcija, 156.–157. lpp.

Gerasimova, Katerina (2002). Public Privacy in Soviet Communal Apartment. In: Crowley, David and Reid, Susan Emily. (eds.). Socialist Spaces. Sites of Everyday Life in the Eastern Bloc. Oxford; New York: Berg, pp. 207–230.

Gordons, Franks (1988). Dienas un nedienas. Stokholma: Memento.

Grīnberga, Mērija (2021). Mana pasaku zeme. Atmiņas un dienasgrāmatas. Rīga: Latvijas Mediji.

Kasparovica, Marija un Zvidriņš, Pēteris (1988). Iedzīvotāji. No: Jērāns, Pēteris (galv. red.). Enciklopēdija Rīga. Rīga: Galvenā enciklopēdiju redakcija, 32.–39. lpp.

Kolbergs, Andris (1985). Automobilī, rīta pusē. Karogs, Nr. 8, 15.–72. lpp.

Melbergs, Gunārs (1989). Dzīvoklis–2000. Māksla, Nr. 6, 34.–35. lpp.

Mežgailis, Bruno (1985). Padomju Latvijas demogrāfija: struktūra, procesi, problēmas. Rīga: Avots.

Oga, Jānis (2022). Varai neērta rakstnieka piemiņa un (literārais) mantojums. Ēvalda Vilka piemērs (1976–1978). Letonica, Nr. 45, 78.–111. lpp.

Radzobe, Silvija (2011). Uz skatuves un aiz kulisēm. Rīga: Zinātne.

Riekstiņš, Jānis (sast.) (2004). Migranti Latvijā 1944–1989. Dokumenti. Rīga: Latvijas Valsts arhīvs.

Rozenberga, Ārija (1967). Dzīvokļu celtniecības kooperatīvs. No: Samsons, Vilis (atb. red.). Latvijas PSR Mazā enciklopēdija. 1. sējums. Rīga: Zinātne, 441. lpp.

Rubīns, Jānis (2004). Rīgas dzīvojamais fonds 20. gadsimtā tipoloģiskā rakursā. Rīga: Jumava.

Slezkine, Yuri (1994). The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism. Slavic Review, Vol. 53, No. 2, pp. 414–452.

Strautmanis, Ivars (1987). Vai celsim savu māju? Zvaigzne, Nr. 10, 18.–19. lpp.

Tarvids, Aivars (1987). Simultānspēle. Dūmi. Rīga: Liesma.

Vilks, Ēvalds (1989). Cilvēks aiz durvīm. Jūrmala, Nr. 24 (1529), 22.06., 7., 12. lpp.