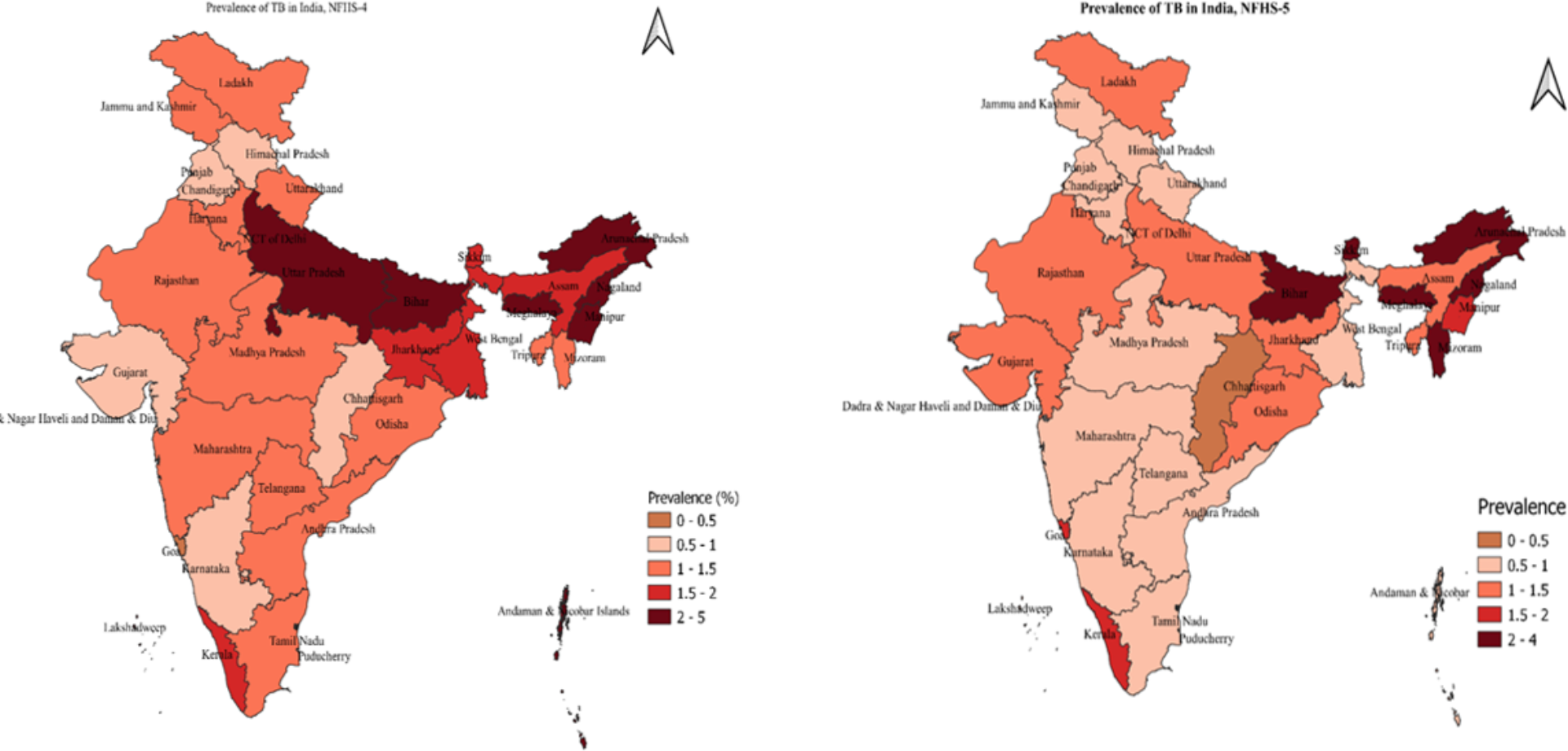

Our study’s findings, indicating a decline in TB prevalence from 1.7 to 1.2% among households having children and adolescents, aged 6–17 years in India, are a significant insight into the country’s fight against TB. The decline in TB prevalence aligns with global trends but also highlights specific challenges within the Indian context. Risk of TB is found higher among kaccha household and semi pucca household than those residing in pucca households. Also, risk of having TB was higher among households without a separate kitchen, using unclean fuel, no electricity, unimproved access to toilet and overcrowded household. Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) initiative, aimed at providing affordable and quality housing, particularly in rural areas, may have contributed significantly to reducing TB prevalence. The Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana, which aims to distribute LPG connections to below-poverty-line families and Swachh Bharat Mission, focusing on improving sanitation and hygiene across the country, also play a crucial role. By reducing reliance on biomass and other polluting fuels for cooking, this program likely contributes to better respiratory health and a lower incidence of TB. The risk of TB declined substantially with an increase in the wealth index of the household. The integration of these socio-economic development programs with health initiatives like the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program (RNTCP) and the National Tuberculosis Elimination Program (NTEP) ensures a more holistic approach to TB prevention and treatment. These programs’ emphasis on early diagnosis, treatment adherence, and community health education is essential in controlling TB spread.

Results from China are in agreement with the noteworthy decrease in TB incidence that occurs as socioeconomic status increases [16]. Poor living circumstances, inadequate access to health care services, and poor nutritional status have all been linked to low income, which increases the risk of contracting mycobacterium TB [17,18,19]. Studies have highlighted the inverse relationship between socio-demographic Index (SDI) and TB incidence. A study found that lower SDI areas tend to have a higher burden of TB, indicating a clear association between socio-economic factors and TB incidence [20]. The influence of living conditions and access to health services on TB risk has been observed widely [21]. In unadjusted model, the urbanites were at lesser risk of having TB. These findings support the idea that individuals in less stable housing conditions face a greater risk of TB, highlighting the importance of improving living standards and socio-economic conditions as part of TB prevention strategies [20, 21]. However, in the adjusted model, urban residence increased the risk of having TB.This calls for further investigation, considering potential urban-specific factors like overcrowding in slums, limited access to healthcare in certain urban pockets, or the emergence of new transmission dynamics in urban settings.

Previous studies have discussed how the use of unclean fuel for cooking, often in homes without a separate kitchen, leads to poor air quality, thereby increasing the risk of respiratory infections like TB [22]. A study identified several factors significantly associated with TB in children. These include HIV infection, a positive TST, and exposure to household smoke [11]. The lack of electricity, often a marker of socio-economic deprivation, is associated with poor health outcomes, including a higher susceptibility to infectious diseases such as TB [23]. Similarly, inadequate sanitation facilities, are a critical factor contributing to the spread of infectious diseases, including TB [24]. Overcrowded living conditions, which exacerbate the transmission of airborne diseases like TB, are also well documented in literature [25].

Our study did not show any significant difference in the prevalence of TB among male and female. However, Higher TB incidence has been reported among males compared with females in other parts of the worlds [1, 26]. The analysis demonstrates a significant correlation between these socio-environmental factors and TB prevalence, with the burden disproportionately impacting poorer households. These findings become more important in the Indian pediatric population in lack of routine screening and treatment where there exists a gap in understanding latent TB particularly in under-five children [13]. This suggests a broader trend of under-diagnosed and potentially under-treated TB in this vulnerable age group. Similarly, a study on adolescent TB in ICU settings throws light on the severity of TB in different age groups and the challenges in managing severe cases, especially in resource-limited settings like India [12]. Comparing these findings with existing literature, our results align with previous studies [12, 13], emphasizing the need for targeted research and resource allocation in high-risk groups. Chadha et al. (2019) also highlight regional variations and higher TB prevalence in rural areas [8], mirroring our findings of increased TB risk in less developed living conditions. Researchers discuss the global burden of pediatric TB [6, 14], underscoring the challenges in diagnosis and reporting that are also evident in our study. The study’s findings on wealth-related inequalities in TB prevalence further reinforce the hypothesis, demonstrating a significant socio-economic gradient in TB risk.

The analysis of the NFHS-4 and NFHS-5 datasets reveals substantial improvements in the living conditions in India, which correlates with a decrease in TB (TB) prevalence. The observed decrease from 1.7 to 1.2% in TB prevalence resonates with global efforts to combat infectious diseases [1]. However, the diagnosing TB in young children is complex due to the high rates of extrapulmonary TB mirroring the calls for child -focused health policies [11]. As found in our study, a systematic review underscores that the risk factors for TB are not only biological but also deeply rooted in socio-economic and environmental conditions [27]. In line with our findings, studies have highlighted that overcrowded living spaces and poor ventilation are identified as prominent risk factors for TB exposure and transmission [27].

Globally, as indicated by previous researchers [6, 14], the challenge of pediatric TB lies in diagnosis and reporting. Our study extends this understanding to the Indian context, where socio-demographic factors significantly impact the incidence of TB. This highlights the need for public health strategies that are sensitive to the socio-economic realities of high-burden countries like India. The National Tuberculosis Elimination Program (NTEP), while making significant strides in addressing TB, faces challenges in reaching the most vulnerable populations, particularly children in remote or impoverished areas. The Indian scenario underscores the need for targeted approaches to tackle pediatric TB, including improved diagnostic methods, more effective public health campaigns, and strategies to address the socio-economic determinants of health.

Developing robust and age-appropriate diagnostic tools and tailored treatment strategies for this vulnerable population remains a critical research area. By analyzing and synthesizing current research, it endeavors to illuminate the epidemiology, risk factors, and management challenges of TB in this vulnerable population, and identify areas where further research and intervention are critically needed. Our research contributes to a deeper understanding of pediatric TB in India. This is particularly significant when considering the findings of Geremew regarding the interaction of TB with HIV in a subset of the population, which, although based in Ethiopia, underscores the complexity of TB in the presence of co-morbidities [28].

Policies should focus on improving housing conditions, particularly in low-income areas. Government initiatives should aim to provide access to clean cooking fuel and reliable electricity. Improving sanitation facilities and access to clean water should also be a priority, as these are fundamental to reducing the spread of TB. Financial assistance and nutritional support programs can alleviate the economic burden on TB-affected families, while expanding free or subsidized diagnostic and treatment services can ensure equitable access to care. Active screening in high-risk, underserved communities, coupled with integration into child and adolescent health programs, can enhance early detection. Strengthening healthcare services in high-risk areas, particularly enhancing TB screening, providing better access to healthcare facilities, and ensuring the availability of necessary treatments could be beneficial. Implementing community-based awareness campaigns can help in reducing stigma and promoting early diagnosis and treatment adherence. The Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program (RNTCP) should focus more intensively on high-risk areas and populations, ensuring early diagnosis and complete treatment adherence. Building on the existing National Tuberculosis Elimination Program (NTEP), continuous research and surveillance are necessary to monitor the impact of interventions and adapt strategies as needed.