It was not an auspicious start to the new year of 1936 for King George V.

The previous year had seen ‘Grandpa England’, as Queen Elizabeth II once called her grandfather, feted during his Silver Jubilee, but long periods of poor health had plagued the King, and he would not live to see February.

By 15 January, he was bedridden with a cold from which he’d never recover. His favourite sister, Princess Victoria, had died in December 1935 and the loss severely depressed him, further depleting him. Add in that the King was on oxygen after decades of smoking, had suffered chronic bronchitis for years, and never fully recovered after being thrown from a horse in his earlier years, and it was obvious that any illness would be detrimental.

So when King George V shut himself in his bedroom at Sandringham House on 15 January, it was an ominous sign. He stayed there until his death on 20 January.

In the final hours of his life, the public was aware that their king lay dying. In a statement written by his physicians, led by Lord Dawson of Penn, it was announced that “The King’s life is moving peacefully towards its close,” at 9:25 pm.

Five minutes before midnight, King George V was dead at the age of 70.

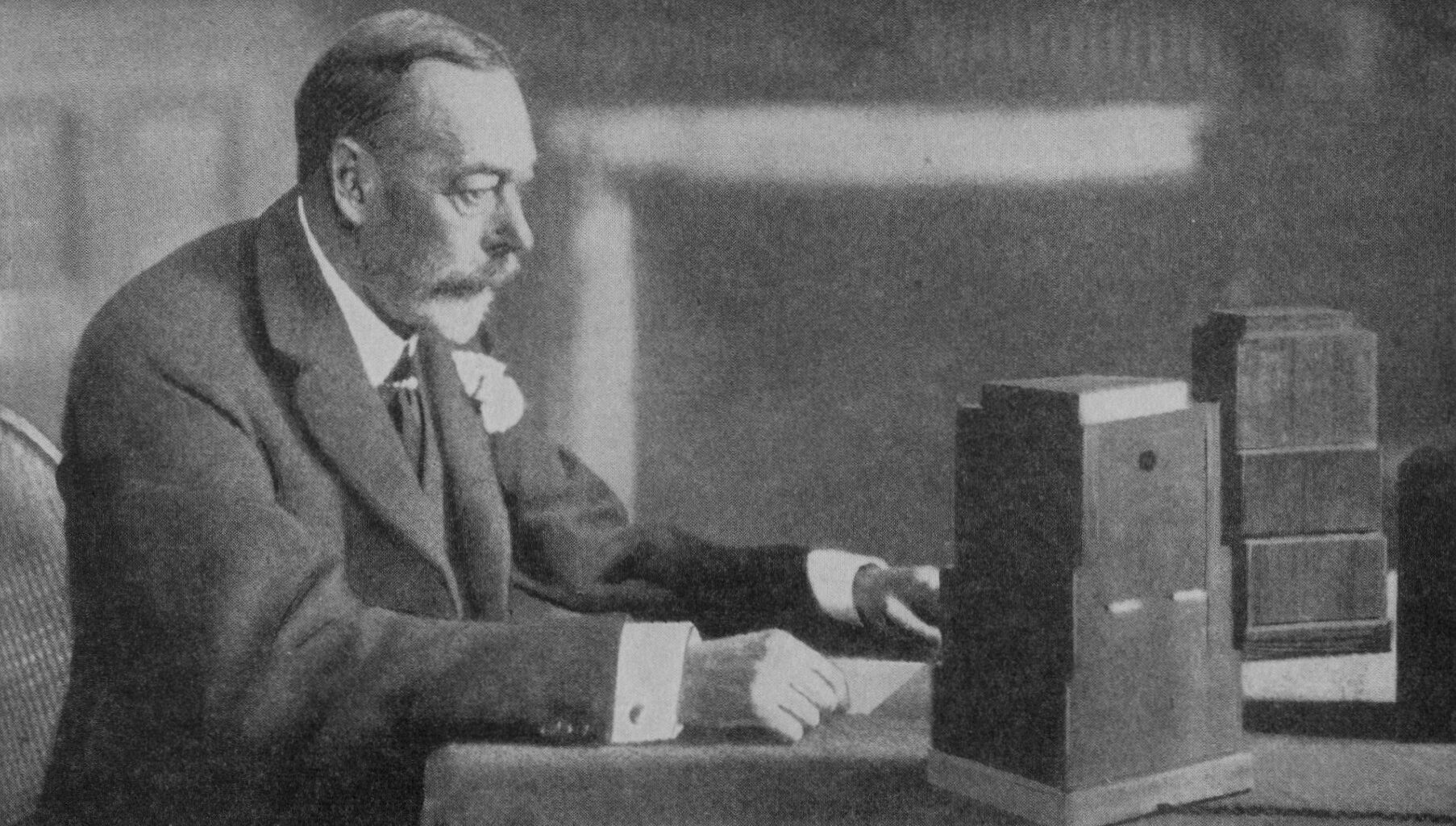

King George V was, in a sense, a modernising king. Granted, he didn’t live to see the advent of television and how it could be used to harness the public image of the British Royal Family; but the monarch is credited—albeit reluctantly—with ushering in the public through the annual Christmas broadcast.

And his death was the first in the modern sense that it could be announced with more than a bulletin.

His father, King Edward VII, died in the final minutes of 6 May 1910 and the world found out in The Gazette through the publication of ‘A Gazette Extraordinary’ with wording that sounded most Victorian: “On Friday night the sixth of May instant, at a quarter to twelve o’clock, our late Most Gracious Sovereign King Edward the Seventh expired at Buckingham Palace in the sixty-ninth year of His age, and the tenth of His Reign. This event has caused one universal feeling of regret and sorrow to His late Majesty’s faithful and attached subjects, to whom He was endeared by the deep interest in their welfare which He invariably manifested, as well as by the eminent and impressive virtues which illustrated and adorned His character.”

Cut to 1936. Shortly after King George V’s physicians announced that the monarch was ‘peacefully’ moving towards death, the British Broadcasting Corporation began providing regular bulletins.

On 21 January, the United Kingdom woke up to the news that their king was dead. The official bulletin read: “Death came peacefully to The King at 11.55 p.m. to-night in the presence of Her Majesty the Queen, The Prince of Wales, The Duke of York, The Princess Royal and The Duke and Duchess of Kent. January 20th, 1936. (Signed) FREDERIC WILLANS, STANLEY HEWETT, DAWSON OF PENN.”

British Pathé quickly released a retrospective calling him “more than a king” to his many subjects. Within six hours, German composer Paul Hindemith wrote ‘Trauermusik’ in the late king’s memory and it was performed on BBC Radio that evening.

King George V’s state funeral occurred at St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle on 28 January. The funeral procession was filmed and shown in theatres as newsreel presentations; the funeral itself was broadcast live on BBC Radio and heard around the world.

But underneath the veneer of the public mourning for a monarch who’d gone ‘peacefully’ in the minutes before midnight was a secret that would remain under wraps for 50 years: that King George V had not, in fact, had a peaceful end, and that he had been euthanised to ensure that his death would be announced in the morning papers.

Lord Dawson of Penn wrote in his private diary about the evening of 20 January 1936 very candidly: “At about 11 o’clock it was evident that the last stage might endure for many hours,” he wrote. King George V was not dying fast enough to make the morning news, and rather than letting the family spend untold final hours holding vigil at their patriarch’s side, the doctor made a decision.

“Hours of waiting just for the mechanical end when all that is really life has departed only exhausts the onlookers & keeps them so strained that they cannot avail themselves of the solace of thought, communion or prayer,” Lord Penn later wrote.

To that end, and to the end of King George V, Lord Penn decided that an injection of morphine and cocaine into the jugular vein would hasten death and give the monarch a fitting end. “In about 1/4 an hour – breathing quieter – appearance more placid – physical struggle gone.”

Lord Penn wanted the King’s death to be announced in The Times, a morning newspaper, over a ‘less appropriate’ evening journal. And to ensure that this would happen, he enlisted his wife to call The Times and have them hold publication, which they did. The next morning, The Times featured the late king in profile, with the announcement: “It is with the most profound regret that we have to announce the death of His Majesty King George, which occurred at 11:55 last night…”

The physician had made the decision without the support, nor the permission, of Queen Mary or the Prince of Wales—later Edward VIII, briefly—and did not tell them of his decision. The public only learned of Lord Penn’s actions in 1986, when his diaries were read by researchers and the shocking news published. By then, all of King George V’s immediate family—his wife and four sons—were dead. If his granddaughter, Queen Elizabeth II, his beloved Lilibet, had a reaction to the news, it was never publicly shared.

In the nearly 100 years since King George V’s death, only two other monarchs have died.

King George VI died unexpectedly at Sandringham on 6 February 1952. His death was shared amongst government officials using the code word ‘Hyde Park Corner’ so that anyone listening in on telephone lines couldn’t decipher the meaning.

The news was held back from the public for several hours owing to the fact that his daughter, the new Queen Elizabeth II, was on a tour of Kenya and had to be contacted before the general public could be made aware. At 11:15 am that morning, the BBC broke the news: “It is with the greatest sorrow that we make the following announcement…” After making seven separate announcements of the king’s death, the radio then went silent for hours out of respect.

Several aspects of King George VI’s funeral and his daughter’s accession were recorded and broadcast on television for the first time, and events were dutifully reported on for radio.

If the media aspect of King George V’s death was the moderniser, King George VI’s death was the branch extending to the truly modern era.

Seventy years later, on the last day of Queen Elizabeth II’s life, Buckingham Palace issued a statement that faintly echoed that of her grandfather’s in 1936: “Following further evaluation this morning, The Queen’s doctors are concerned for Her Majesty’s health and have recommended she remain under medical supervision. The Queen remains comfortable and at Balmoral.”

On 8 September 2022, at 3:10 in the afternoon, Queen Elizabeth II died peacefully at Balmoral.

In the age of instant information and social media, the news was still kept quiet for over three hours. An announcement came at 6.30pm that evening and was simultaneously shared by the BBC on television and radio and through Buckingham Palace’s social media accounts: “The Queen died peacefully at Balmoral this afternoon.

“The King and The Queen Consort will remain at Balmoral this evening and will return to London tomorrow.”

Every aspect of Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral—from the vigils at the gates of Balmoral, Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle and Sandringham to the procession from Scotland back to London, from the lying-in-state to the funeral service at Westminster Abbey and the committal at St George’s Chapel—was broadcast to the world.