Russian President Vladimir Putin has declared 2025 the “Year of the Defender of the Fatherland,” but the soldiers whose patriotism he wants to champion could pose a threat to his rule when they return from fighting against Ukraine.

That assessment by the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) follows moves by the Kremlin that the Washington think tank said aim to stop veterans-based civil society emerging from traumatized and disgruntled troops challenging state propaganda about the war.

One security expert told Newsweek that the Kremlin could be threatened by veterans returning to civilian life and reminding the Russian people of the huge human cost that the authorities had hidden.

A Putin critic who is on Russia’s federal wanted list told Newsweek that returning soldiers did not pose an immediate danger to the regime but could fuel a crime wave far worse than seen following the break-up of the Soviet Union. Newsweek has contacted the Kremlin for comment.

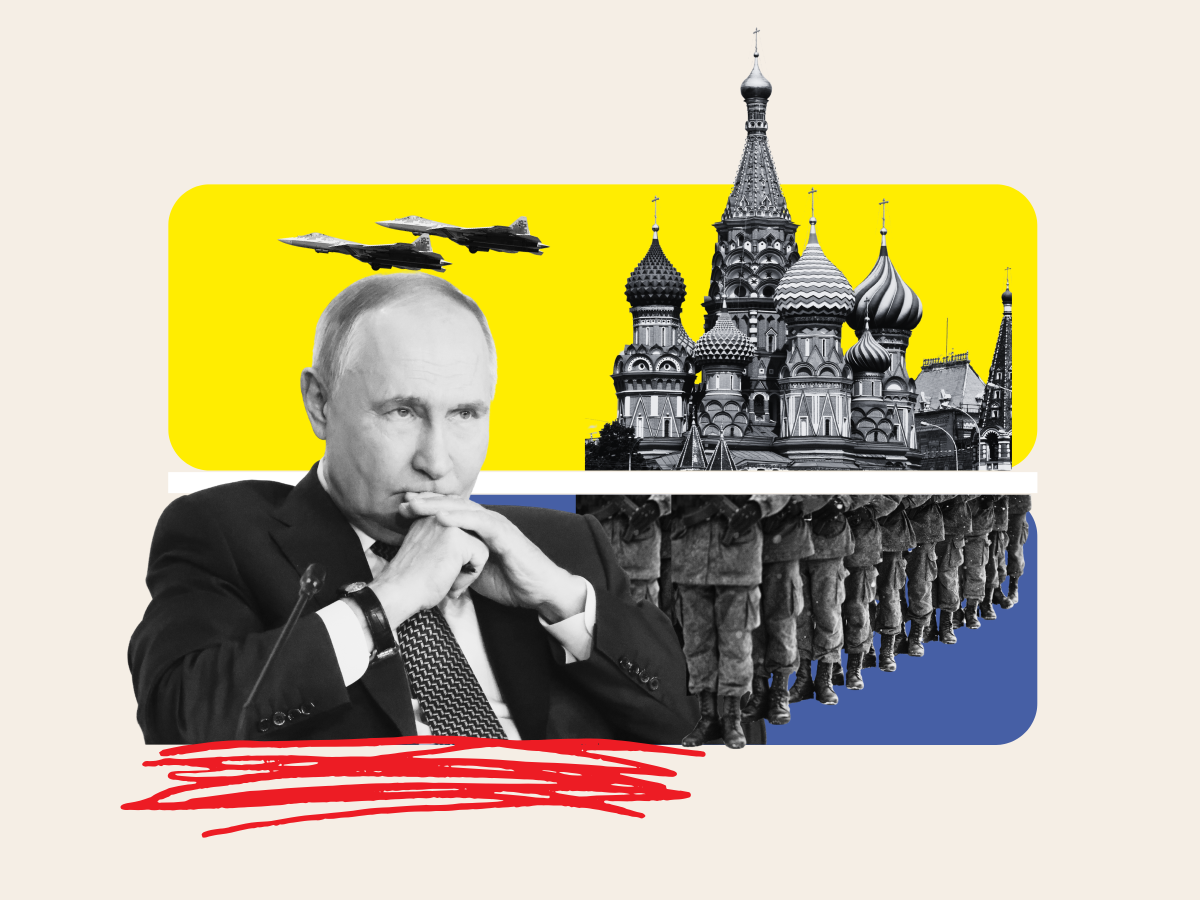

Newsweek illustration/ Getty Images

The Afghanistan Experience

Using the euphemism for its aggression in Ukraine, the Kremlin has launched initiatives over the last two years called the Association of the Special Military Operation (SVO) and the SVO Military Brotherhood.

These movements ostensibly supporting and elevating military service are also measures to keep veterans on a leash, the ISW said.

The Kremlin is keen to stop independent civil society groups of veterans struggling to reintegrate into the community because of trauma, the think tank said, noting how Moscow wants to avoid a repeat of the social instability that followed its withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989, a decade after its invasion.

The ISW says the Kremlin fears a new wave of “Afghan syndrome” in which veterans’ groups known as Afghantsi (Russian for Afghans), returned disillusioned at the Soviet government’s inability to integrate traumatized veterans into society.

“The troops returning do pose as a security risk,” said Seth Krummrich, a former U.S. Army colonel and vice president client risk management at security firm Global Guardian, “maybe not in the short term, but they represent a serious mid- to long-term problem for Putin’s regime and any subsequent Russian government.”

The number of Russian casualties and details of the war that are tightly controlled by the Kremlin could become more widely known, fueling a resentment that may not be offset by any government program to herald the bravery of the veterans.

“When the truth and financial support are not provided to the families, real trouble and social unrest will rise,” Krummrich said. “Over time, the propaganda will ring hollow when the State can’t provide the WIA [wounded in action] veteran support services in the coming years.

“Much like their Afghan campaign, the massive number of WIA will be on full display daily in Russian life, a constant reminder of how Russia deceived its own people.”

Fear of a ‘Crime Wave’

Russia scoured its prisons to help boost numbers for its forces in Ukraine by offering a pardon and freedom after six months of fighting.

While this deal is reportedly no longer available, Sergei Kiriyenko, a Russian presidential administration official, reportedly told a government meeting in July 2024 that Moscow’s veterans “adapt poorly” to civilian life as he raised alarm at how veterans’ crimes could cause civilians to view them with discontent.

Kiriyenko said demobilized Russian veterans from Ukraine face a different society than returning troops from the Afghan war or World War II because Soviet society was more mobilized and in a better position to support or wage conflict.

Returning Russian soldiers could be the country’s “biggest political and social risk factor” during Putin’s presidential term as society reacts with “fear” and even “aggression” to all military personnel, Kiriyenko reportedly said.

Konstantin Sonin, a Russian-born economist who was issued an arrest warrant this month in Russia for allegedly spreading false information about its military, said veterans were not an acute threat to Putin’s power given his commitment to finding new troops but did pose other risks for Russian society.

“There will be a major crime wave larger than the crime wave in the early ’90s,” he told Newsweek. “There will be many more, up to 10 times more, veterans than after the Afghan war. They will be well trained in how to use weapons and will be easy recruits for any criminal groups.”

“Plus, Putin’s government did a lot to destroy the credibility of the criminal system. A whole generation of criminals know that whatever you do, you can be exempted from punishment if you go to war,” added Sonin, a professor at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago.

Russian honor guard soldiers at an exhibition of Western military equipment captured by Russian forces in Kharkiv and Sumy regions of Ukraine in St. Petersburg on November 4, 2024.

Russian honor guard soldiers at an exhibition of Western military equipment captured by Russian forces in Kharkiv and Sumy regions of Ukraine in St. Petersburg on November 4, 2024.

OLGA MALTSEVA/Getty Images

Comparisons of Moscow’s invasion of Afghanistan four decades ago hang over Putin’s February 24, 2022, invasion of Ukraine. Moscow entered both conflicts in the mistaken belief they would be over quickly. Keenly aware of the ability of veterans to strengthen or destabilize society, Moscow is keen to quash political movements that discredit Russian authorities.

Veteran opposition movements between 2022 and 2023 saw patrons try to weaponize Russian servicemen and veterans to advance personal political objectives, such as former officer Igor Girkin, who played a key role in the annexation of Crimea, and Wagner Group mercenary chief Yevgeny Prigozhin.

The latter died in a plane crash following a rebellion against Putin in June 2023 and the former has been jailed following his criticism of Russian authorities.

The ISW said that the Kremlin has thus managed to curb the immediate threat to Putin of alienated veterans’ civil society.

The Kremlin has also formed state-run veteran organizations that centralize Putin’s control over previously semi-independent forces such as the thousands of Wagner mercenaries via the Defenders of the Fatherland State Fund. Meanwhile, the Kremlin’s “Time of Heroes” program has installed dozens of loyalists into positions of power.

Military analysts Harry Francisco Stevens and Thomas Lattanzo wrote in War on the Rocks this month that a post-war Russia could see a new class of loyal bureaucrats who can enable Putin to clear the government of those he is dissatisfied with.

A survey by the independent Russian pollster the Chronicles project in September 2024 found more soldiers signed up for the war for the money (37 percent) in which they received up-front payments of up to $35,000, than out of civic duty (24 percent) and those who survive will return to towns and villages adapting to relatively high wealth levels.

However, with the Russian death toll in Ukraine, which could be as high as 211,000, how veterans integrate into civilian life and how society views them may be shaped by the extent to which the truth of the war’s human costs is revealed.

Sonin noted that Afghan veterans returning home expressed their discontent when the war’s losses of 15,000 were much smaller: “I would expect that Ukraine war there would a similar dynamic—a point in which everybody talks about the people killed.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin at the Grand Kremlin Palace on February 26, 2025.

Russian President Vladimir Putin at the Grand Kremlin Palace on February 26, 2025.

Getty Images