Hungary’s political landscape shifts as Peter Magyar challenges Orban’s pro-Trump, pro-Russia stance. From Respekt

The response of the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban to the recent spat between Trump and Zelenskiy was not surprising. What wasn’t surprising either was the literary form he chose, because this is how he likes to do it. In any case, he called the Ukrainian president and almost all of the rest of Europe weak because they want war, and he ranked Trump among strong men, because he wants peace. Judging by his previous statements, other similarly strong men include himself, the Pope, and now probably also Putin. Many Hungarians, however, probably think differently.

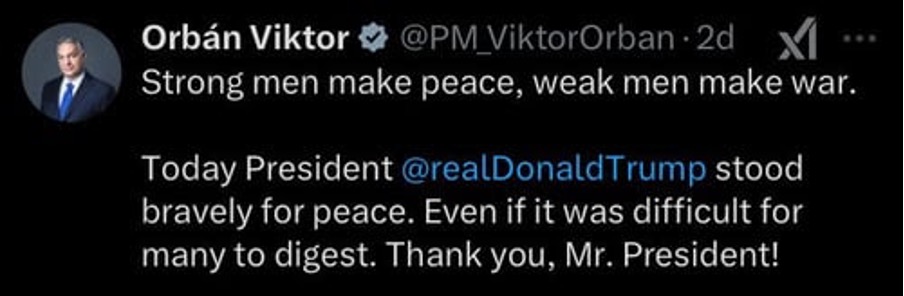

Hungarian PM Viktor Orban praises Donald Trump for his stance on peace. Photo via his X account (@PM_ViktorOrban).

For all observers of this remarkable country – as well as for Hungarians themselves – the question of “what do Hungarians think” is a complicated one. Opinion polls do not help out a great deal. In polling, Hungarian citizens express an increasing dissatisfaction with the state of education, healthcare, and the country as such. However, the electoral victories of Orban’s Fidesz, which has been governing the country since 2010, are still absolutely decisive. In the space of a few short years, government propaganda has managed to turn a passionate hatred of Russians into something like an unenthusiastic friendship, or at least a feeling that they are less evil than anyone else. Hungary is a society that ranks close to the very top when it comes to satisfaction with EU membership. But its prime minister does not engage in minor complaints when it comes to the EU, similar to those of Andrej Babis, the former Czech prime minister. He comes up with completely fantastic and bizarre conspiracy theories about the Union. What, then, do the people of Hungary think about the world around them, and what sense does it all make?

Just as obvious as what Orban would say about the argument in the Oval Office was what the rest of Hungary’s political scene would say. The openly fascist Our Homeland movement agreed with the strong men. Established centrist and leftist opposition parties, as well as smaller, fading parties, condemned Trump’s behavior as despicable and extempore.

The only real Hungarian opposition at the moment, the Tisza movement of former Fidesz member Peter Magyar, went about it differently. Magyar said Orban was turning Hungary into the world’s first joint American-Russian colony, which is treason, because Hungarian history shows the country must be strong and not trust anyone.

What exactly this means is a good question. Magyar does not explain his positions any more than he thinks is necessary. He presents himself – in contrast to Orban – as someone who has partners in Europe, whom people talk to, who’s not ostracized. Perhaps, then, a strong Hungary means a perfectly standard EU state. But that’s not the point. Obvious resistance to Russia and Trump is what’s interesting here.

Magyar and his party have been on the political scene for less than a year. Their approximately 40 percent support in the polls – similar to or higher than that of Fidesz – has been holding steady for several months now. They are not the “opposition flavor of the month,” as Fidesz politicians used to mock them. And Magyar’s opinions – or rather, all the issues that Magyar has dared to have an opinion on – are clearly expanding. At first, Magyar would only talk about bad hospitals, corruption, and that Hungary could do better. Things that just about everyone can agree on. That’s how he’s reached his current popularity. Later on, he has had to broaden his scope of topics, and he’s done so successfully. Either he has good instincts, good researchers, or he’s simply good at listening to what people are telling him.

For example, part of his self-promotion is helping poor people. That means the really poor, including the Roma. This is not exactly a popular attitude in Hungary. The Roma, as well as the long-term unemployed, are among the groups that Fidesz has chosen as scapegoats. Magyar says women don’t belong in the kitchen – they belong in the government. And they belong there more than men do, which is why, he says, they will form more than half of his future cabinet.

The contrast with what the governing party is saying couldn’t be any greater. When the Russians used a missile to hit a children’s hospital in Kyiv, he drove there to bring humanitarian aid, and so on. Magyar is not what is known as an urban liberal politician. He doesn’t ride around town on his bike – he gets his pictures taken in a sports car. Also, he really, really cares about looking good. Maybe that helps him among the broader public. What’s important is that he often says and does the very opposite of Fidesz – and that doesn’t take away from his popularity, quite the contrary.

Now he’s saying that being best friends with Trump and Putin is stupid – or even treason. And there’s every reason to believe that in this case, too, he’s understood what a significant part of Hungarians think.

Tomas Brolik is deputy editor-in-chief of Respekt, the leading Czech newsweekly where this article originally appeared. Republished by permission. Translated by Matus Nemeth.