Amid political turbulence, South Korea and the United States must build a more strategic nuclear cooperation model—one that unlocks new export opportunities, can meet rising energy demand, and attracts the financing needed to scale deployment.

The nuclear energy policies of Washington and Seoul are caught in unprecedented political upheaval. This is just months after launching a new path for cooperation by settling a six-year-long fight between the two nations’ largest nuclear companies.

President Trump’s tariff tear is creating international economic chaos. And the recent removal of Yoon Suk-Yeol as South Korea’s president is fueling the seemingly perpetual political churn in Seoul.

Political Turbulence

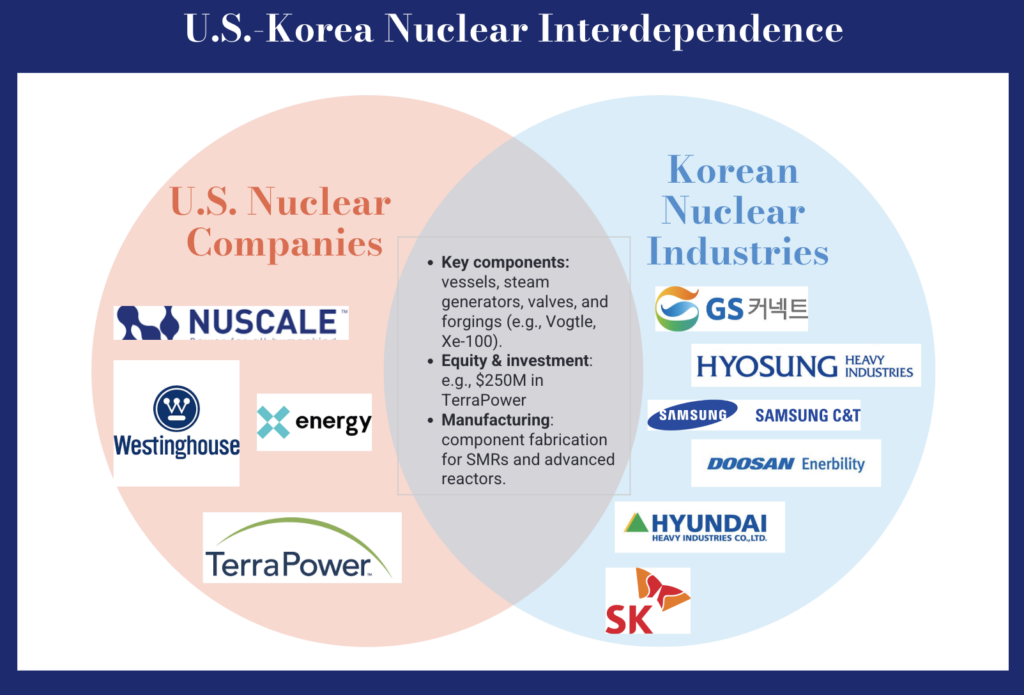

The Trump administration’s 25 percent tariff on South Korea (now partially reprieved) could undermine the president’s determination to dominate the global nuclear energy market at home and abroad because the U.S. and Korean nuclear industries are deeply entwined and mutually dependent.

The Korean constitutional court’s decision on Yoon means a new presidential election must be held before June 3, and it likely will result in yet another change of party control.

Yoon’s policy was avowedly pro-nuclear and called for a rise of domestic nuclear generation from 31.4 to 35.6 percent in the nation’s energy mix. This would entail completing three additional reactors. In addition, Yoon called for the export of ten Korean nuclear reactors.

The upcoming election’s front-runner is now Lee Jae-myung, the leader of the Democratic Party. That party’s energy policy has been to reduce Korea’s reliance on nuclear power and focus on renewables backed by natural gas. The previous Democratic Party president, Moon Jae-In, sought to phase out nuclear power dependence in South Korea while nominally supporting reactor exports.

However, it may be difficult for Lee to completely backtrack on Yoon’s nuclear goals.

South Korea has endorsed the pledge to triple nuclear energy globally by 2050. It is also moving forward with two new reactors at home, and Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP) has been chosen to build two new reactors in the Czech Republic.

While Korean Democratic Party parliamentarians have attacked the Czech deal as “shabby” and a financial giveaway to secure the contract, it seems unlikely that Lee will pull out of the deal. The project is estimated to be worth over $17 billion and is Korea’s first export contract since 2009, when it won the tender to build four nuclear reactors in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). America’s Westinghouse will also benefit from the Czech deal through significant subcontracts.

Source: Jocelyn Livier, Della Ratta Energy and Global Security Fellow, Partnership for Global Security

Source: Jocelyn Livier, Della Ratta Energy and Global Security Fellow, Partnership for Global Security

Dependency and Deals

It is this symbiotic relationship between the Korean and American nuclear industries that needs to outlast the political chaos and expand as the international environment demands more nuclear power for energy security, geopolitical, and zero-carbon purposes.

The two countries worked well together on the Barakah nuclear project in the UAE. While a Korean-led reactor construction project, Westinghouse was a major subcontractor, earning about $2 billion by providing components, engineering support, and project support.

Westinghouse now has firm multi-reactor export commitments in Poland and Bulgaria and is working with other European nations, including Slovenia, Slovakia, and the Netherlands. With Westinghouse as the lead contractor, multiple Korean companies will substantially benefit from subcontracts.

But there is now the opportunity to move beyond the existing collaboration structure and forge a new nuclear cooperation construct based on opportunities emerging from the evolving international energy environment.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is one potential opportunity to create a new dimension of U.S.-Korean nuclear cooperation in a third country.

Before the October 2023 Hamas attack on Israel, a major strategic agreement was brewing between the United States, Israel, and Saudi Arabia that included American support for the kingdom’s nascent nuclear power project.

Momentum for this deal fizzled late in the Biden administration, but Trump has a different relationship with the kingdom and with Israel’s leaders. He plans to make his first overseas trip to Saudi Arabia in May.

U.S. support for Saudi civil nuclear power would be prohibited without an agreement for nuclear cooperation between the two countries, which has never had a high probability of success for a variety of political and international security reasons. However, Secretary of Energy Chris Wright recently indicated that a U.S.-Saudi commercial nuclear power deal is possible, including a potential resolution of the sensitive issues “that involve [uranium] enrichment here in Saudi Arabia.”

Wright further noted that “It’s critical that it becomes the United States as the partner.” U.S. officials do not want to see the Saudis move on to Russia or China as their nuclear supplier of choice. One goal of the hamstrung trilateral deal was to break the kingdom away from dependence on China. And recent U.S. tariff policy has placed a bullseye on China’s export practices.

Saudi officials have been impressed with the UAE-Korea cooperation at Barakah, and a Republic of Korea (ROK) lead in the kingdom’s nuclear project is also possible. It would be politically and legally complicated because a Korean reactor still needs a U.S. export license based on its American components. But there could be a creative path forward if the 123 agreement fails.

AI Data Centers

Less daunting is the opportunity for Korea to cooperate with American firms as they build new reactors on U.S. soil.

AI and its data centers are accelerating projected U.S. energy demand rapidly. Major tech companies and states are jumping on the opportunity to deploy nuclear energy to power these technologies. In some scenarios, the energy production from these small conventional and advanced reactors would be solely dedicated to the data center, not the electric grid.

The U.S. government is also scoping out federal locations that could be used for data center development, with the goal of accelerating the construction of the centers and their energy source. Many of the sites are at national laboratories that are already deeply involved in nuclear power development and fuel manufacturing.

Advanced reactors that run on exotic fuel cycles are still five to ten years away from deployment, but small modular reactors (SMRs) using a conventional fuel cycle, like NuScale’s VOYGR and Westinghouse’s AP-300, could be deployed more rapidly.

If the demand for nuclear-powered data center campuses moves from concept to reality, there will be a growing need for engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) support. This is an area where Korea and the United States could create a nuclear cooperation game changer.

Korea is well known as an efficient EPC nation, building the four reactors in the UAE essentially on time and within budget and at a much lower unit cost than U.S. reactors. Domestic U.S. reactor construction has been beset with ballooning budgets and delays and has been dependent on America’s major EPC contractor, Bechtel.

If U.S. SMRs or advanced reactors were to be built out for AI data centers, coal-to-nuclear clean energy transitions, or to supplement existing utility electrical output, there is a question of whether the United States would have enough EPC capacity. This is where Korea and the United States could come to cooperate on U.S. soil in an unprecedented way.

Innovative Financing

Further, the 2024 ADVANCE Act relaxes the previous legal ban on majority foreign ownership of U.S. nuclear facilities. This opens the opportunity for joint U.S.-Korean (and perhaps other allied nations) financing and control of these new reactors.

America has gone on a massive nuclear spending spree over the last five years. Billions of dollars have been allocated to developing new reactors, creating the fuels that they run on, restarting shut-down reactors, keeping existing ones operating, and supporting U.S. reactor exports. The concerns that the Trump administration would choke off the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office now seem unfounded, at least for nuclear and fossil energy.

But the commercial financial markets still remain hesitant to enthusiastically support nuclear deployment due to a number of obstacles, including the EPC inefficiency of past projects and the challenges associated with deploying the first-of-a-kind reactor.

This will require the U.S. government to move beyond its current support system and bring more money and risk reduction to the table.

A recent re-issuing of a $900 million solicitation by the Department of Energy is a step in the right direction. It is now focused on deploying Gen III+ and SMRs using light water fuel cycles and offers the biggest payout to “first movers” and “fast followers.” It seeks to incentivize the creation of an order book to stimulate reactor deployment at scale.

This approach is completely consistent with President Trump’s deal-making ethos.

But $900 million is not nearly enough and there will have to be a follow-on commitment to ensure continued deployment and exports.

A major challenge is to determine how to mitigate cost overruns and risk in new nuclear projects in order to entice the private sector to jump in while limiting moral hazard.

This is where the U.S. and Korean governments could collaborate on a financing plan. They could create an overarching political commitment to financially support nuclear deployment at a steady pace and then identify the financing and conditions on a deal-by-deal basis.

This is the kind of new nuclear cooperation that can pull American and Korean nuclear policy out of the chaotic political undertow and advance their collective strength in nuclear deployment for the remainder of the century.

Kenneth N. Luongo is the president and founder of the Partnership for Global Security (PGS) and the Center for a Secure Nuclear Future.

Image: Walt Bilous/Shutterstock