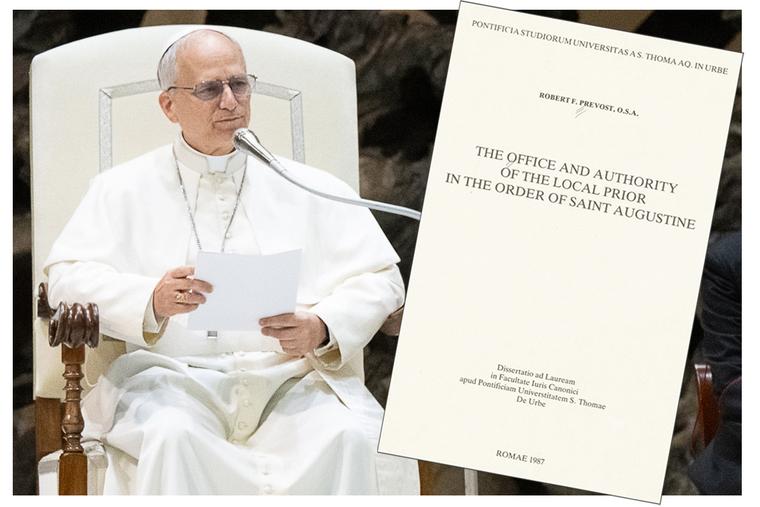

Before he became Pope, Leo XIV was Augustinian Father Robert Prevost, a quiet friar studying the inner workings of religious life. He earned a licentiate in canon law from the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas (Angelicum) in Rome in 1984, followed by a doctorate in 1987. His dissertation, titled “The Office and Authority of the Local Prior in the Order of Saint Augustine,” may seem obscure at first glance — but it could now offer valuable insight into the kind of pope he will be.

I had the opportunity to read Pope Leo’s dissertation thanks to the support of the Province of St. Thomas of Villanova and the Falvey Library and Archive Team at Villanova University. Perhaps eager to see one of their own — formed in the Augustinian tradition — reflect on this papacy, they granted access. Not every researcher might have been extended the same trust, and I don’t take that lightly. I’m grateful to the Augustinian community, and I hope this piece does justice to the richness of what I found.

What follows is a brief look at how that early work may help illuminate the instincts and vision of the new Pope.

The Quiet Authority of Pope Leo XIV

As Pope Leo XIV becomes more familiar with his flock, so, too, do members of the flock grow familiar with their new shepherd. Encyclicals, apostolic exhortations, speeches and homilies will come in due time. But even now, there are signs he carries something deeper: a theological vision shaped by the quiet, deliberate rhythms of Augustinian life.

That vision became strikingly clear as I read the Holy Father’s dissertation. The work does not dwell on global structures or ecclesial politics, but on the smallest, most intimate unit of religious life: the local community. In the details of how a prior (superior) leads his brothers, Father Prevost lays out a theology of authority that is as ancient as the Gospel and as urgently needed as ever.

When Father Prevost writes about the local prior, he is not merely offering commentary on monastic leadership. He is presenting a model of governance that clearly scales upward. The Pope’s “community” is now the universal Church. The same principles of unity, discernment and service apply — only now on a global stage.

One of the most significant voices invoked in the dissertation is that of Pope St. John Paul II. The longest quoted passage in the entire work comes from a 1982 address the Polish Pope gave to the Augustinians gathered in the chapel of their International College in Rome. John Paul reminded them that their identity is shaped not only by the Rule of St. Augustine but also by the juridical foundation given to them by the Church: “Your Order … has holy Mother Church for the foundress of its juridic reality.”

For Father Prevost, this is not a contradiction but a convergence: The spiritual charism of Augustine and the institutional authority of the Church together define what it means to lead. The Pope’s exhortation — “Act in such a way that what the Church is on a general plane … may become true for each of your communities” — becomes a kind of rallying cry. Authority, in this light, is always ecclesial: received, structured and lived for the sake of communion.

At the heart of this vision is a distinctive ecclesiology — an understanding of how the Church is structured and led. Leo XIV’s dissertation presents a vision of the Church not as a hierarchy of command, but as a communion of communities, bound together by authority that is at once legal and pastoral, spiritual and institutional.

Authority as Service — Anchored in Law

One of the most revealing moments in the dissertation comes at its close: “Primary emphasis, throughout the entire thesis, has obviously and intentionally been placed upon the juridical aspects of the Prior’s office and duties.” Father Prevost is unapologetic about this focus because, for him, the law is not a distraction from the spiritual life — it is one of the ways that life takes concrete form.

“Religious life, just as the Church as a whole, is a reality made up of visible concrete dimensions and spiritual, charismatic elements as well. Frequently, it is in and through the visible dimension that the charismatic is actualized.”

Law, in this view, does not limit grace; it enables it to be lived in community and in concrete reality.

The foundational claim of the dissertation is this: Authority in the Church is not about domination or control, but about service and communion. As Father Prevost writes, “The Prior’s office in the Order is not an office of power, but of fraternal love; not of honor, but of obligation; not of domination, but of service” (Constitutions, 15).

This should not be mistaken for a vague appeal to niceness or goodwill. Father Prevost’s vision is deeply canonical. He grounds his arguments firmly in the Church’s legal tradition — from the Code of Canon Law to the Constitutions of the Augustinian Order. His leadership model conveys a clear pastoral approach, but it is anything but improvised.

He goes on to say that authority is a “power … received from God through the ministry of the Church” (Canon 618) — a power to be exercised within clear boundaries, guided by law, and directed toward the common good.

So far, this offers a distinct contrast to Pope Leo’s predecessor. While Pope Francis emphasized synodality and pastoral discernment — often without clear structural definitions — Father Prevost’s dissertation suggests he sees no contradiction between synodality and structure. Discernment, he implies, requires form. Dialogue requires rules. The superior’s role is not to suspend the law in the name of mercy, but to interpret and apply it with justice and love. As he writes:

The discernment of God’s will and the receiving of insights as gift from the Spirit are in no way reserved to the superior … it is essential that the search for or discernment of God’s will be undertaken within a context of dialogue. … The superior and the community which he serves must work together in order to arrive at decisions which reflect a real cooperation with what the plan of the divine will would be in the given situation.[

Elsewhere, he adds:

It follows that the substance of the office of the superior is to obey; to obey the will of God and to put great effort into trying to know it, to formulate it and to specify it for his subjects.

Father Prevost conveys a clear sense in the text that he was writing during a moment of ecclesial and cultural transition. He observes that the world around the Church was being shaped by a rising “personalism,” often untethered from the Church’s theology of obedience and law. “Freedom and law are not terms which contrast with one another,” he writes. “They are values which must be integrated with each other.”

In an age increasingly skeptical of authority — let alone authority figures — Father Prevost insists that the Gospel does not abolish authority, but institutes it. “Authority is placed at the service of the good of others … not … because it is derived from the community, but because it is received from above for governing and judging.”

This framework reflects a trust in local initiative (what the Church calls subsidiarity), tempered by the Pope’s responsibility to ensure unity and care for the whole Church — a balance long held as essential to ecclesial governance. This dual commitment of decentralized attentiveness and centralized guardianship appears to be a hallmark of the ecclesiology Father Prevost articulates here.

The Spiritual Shape of Leadership

If this emphasis on law and governance seems abstract, Father Prevost grounds it firmly in the notion of relationship.

“Authority is relational,” he writes. “It would be useless to appoint a man to the office of Prior if there will not be the possibility for a good relationship between him and the other members of the community.” Law, in his view, is never impersonal; it bears fruit only when authority is exercised within real human relationships — marked by trust, listening and mutual service.

Father Prevost’s dissertation is therefore not dry canon law. It is steeped in pastoral concern. Time and again, he returns to the conviction that leadership must be grounded in love, expressed through listening, and oriented toward unity. “The superior is expected to be a living witness to the love of God offered freely and generously to the community,” he writes.

This is more than good management; it is closer to spiritual fatherhood. For Father Prevost, the task of a leader is to model Jesus Christ, to build community, and to nurture vocations to holiness in the midst of ordinary life. He calls it an “ecclesial ministry,” recognizing that even the smallest act of local leadership participates in the Church’s universal mission.

I met Father Prevost in 2010, when he was still serving as prior general of the Order of St. Augustine. I was struck by the same combination of simplicity and interior conviction that now animates his papal vision — qualities already visible in his 1987 dissertation. He didn’t fill the room with charisma; he filled it with steadiness, attention and clarity. These are not qualities that trend — but they are qualities that endure.

From Local Prior to Universal Pastor

The ecclesiology Leo XIV sets forth in this early work affirms that the Church, at every level, is more than a bureaucracy or social movement. It is the Body of Christ, animated by the Holy Spirit and governed through structures that serve communion. His theological imagination links the local and the universal, showing that the Church’s health depends on grassroots vitality and on the unifying role of the Petrine office.

Now, as the Successor of St. Peter and Vicar of Christ, Leo holds the highest office of visible authority in the Church. His decisions will likely feel less like top-down mandates and more like discernments made in consultation with others. This is a style of leadership that some will likely describe as “synodal” — though not in the looser, open-ended sense the term has often taken on in recent years.

Rather, this version of synodality is likely to resemble ordered collaboration, not open-ended experimentation. In the dissertation, the superior is described as “the principle of unity for the community” — a figure who listens, yes, but who also exercises authority with integrity. In this vision, the Church is not a debating society but a body bound together in a shared mission, guided by divine Revelation and the grace of God.

What the Bibliography Reveals

For readers with a more technical eye, the bibliography is telling. It is rich with canonical, historical and theological sources, reflecting a scholar working at the intersection of tradition and reform. Several points stand out:

Legal Precision. References to the 1917 and 1983 Codes of Canon Law, canonical commentaries and proceedings show that Father Prevost takes the Church’s juridical structure seriously. These sources are not afterthoughts — they are theologically central. His bibliography includes major 20th-century canonists such as Cappello, Beyer, Woestman, Wernz, Vidal, Orsy and Andrés Gutíerrez.

Augustinian Roots. With multiple works on the Rule of St. Augustine, the Augustinian Constitutions, and the order’s history, the bibliography reveals how deeply his vision is shaped by the ideal of fraternal community and authority as a form of service.

Postconciliar Engagement. Extensive references to Vatican II documents and to theologians such as Yves Congar reflect a commitment to the Council’s renewal — not as a rupture with the past, but as a work of organic development.

Historical Depth. The inclusion of patristic and medieval sources — such as the Patrologia Latina, Suarez and Tierney — points to a scholar who interprets the Church’s present through the wisdom of her past.

In sum, the sources suggest a pope whose ecclesiology is canonical, spiritual and historically grounded — a pastor-scholar who governs not with slogans, but with structure and vision. His dissertation draws on a wide range of canonical thinkers — some deeply traditional, others shaped by the aggiornamento of Vatican II — signaling a legal mind both rooted and responsive, not beholden to any single school or ideology.

A Pope for This Moment

Many Catholics today are asking: Will this new Pope offer clarity where confusion has crept in? Will he restore trust where it has been shaken? Leo XIV’s dissertation, far from abstract, speaks directly to this moment. It reveals a leader who values dialogue, but not disorder; consultation, but not confusion. He leads with a steady hand and a heart formed by law, prayer and community.

While Pope Leo XIV’s pontificate is only just beginning, his early writing reflects a deep regard for many of the things Catholics today long for: a Church that listens, a shepherd who walks with his people, and a vision of leadership that doesn’t silence the faithful but draws them into deeper communion. Yet unlike the freer forms of synodality seen in recent years, Leo XIV’s approach appears more juridically defined and firmly anchored. His emphasis on respecting the agency of local communities should not be mistaken for disengagement. Rather, it reflects a confidence in the Mystical Body of Christ — one that is never divorced from the broader obligations of the papal office. The local and the global are held together not in tension, but in mutual service.

As he states in the “Introduction” section of the dissertation: “The struggle to find the best way to live authority and obedience in religious life is not over.” It certainly isn’t — and under Leo XIV, that struggle may take a more ordered, canonical shape: one that trusts the law of the Church as a gift, not a hindrance.

The Friar in White

The white cassock of the papacy may be new, but the heart beneath it is familiar. It is the restless heart of an Augustinian priest who has spent his life thinking and praying about how best to serve Christ and the People of God. As his dissertation makes clear, the authority Pope Leo XIV now holds will not be shaped by ambition, but by the cross; not by conquest, but by community. Nor will it be improvised. It will be exercised firmly, clearly, and with love.

This is not a hunch — it’s a confirmation. His dissertation doesn’t upend expectations — it affirms them. Here is a Pope who sees leadership as ordered grace, who values law not for control but for communion, and who believes deeply in the strength of quiet, faithful service. Perhaps that’s precisely what the Church needs now: not a revolution, but a return — to clarity, to charity, and to the wisdom of a simple friar who knows how to lead by serving.