In November 2022, The Sopris Sun published an article on the possibility of one or more nuclear generating plants being built in Western Colorado. It was prompted by an initiative from the Associated Governments of Northwest Colorado earlier that year that favored establishing nuclear power in the region; this was in response to the planned decommissioning of large coal-fired power stations in the state, notably one near Craig, over the next several years.

At that time, there were no such plans for northwestern Colorado, nor anywhere else in the state. However, a project mentioned in that article — a nuclear power station with a small modular reactor (SMR) — broke ground last June near Kemmerer, Wyoming. The new plant will partially replace generation from a coal-fired station there scheduled for decommissioning this year.

HB25-1040

The Sun decided to revisit the issue after Gov. Jared Polis signed House Bill (HB)25-1040 at the end of March, which added nuclear power to the list of renewable energy sources Colorado deems as “clean energy,” making it eligible for grants and incentives available for renewables. The Sun wondered, with this policy shift by the state, if electric utilities might show more interest in nuclear power at Craig and elsewhere.

The short answer is no — at least, not yet. Xcel Energy’s state-approved 2022 Colorado Clean Energy Plan, aiming to eliminate coal-fired stations by 2030, does not include any plans for nuclear power. However, the company has investigated the possibility of utilizing SMR technology in the 2030s.

Likewise, Tri-State Generation and Transmission, a cooperative that operates and partially owns the Craig station, has not yet pursued a nuclear option. In communications with The Sun, Mark Stutz, Tri-State’s public relations specialist, noted that nuclear power is not under consideration in the company’s 2023 Electric Resource Plan (awaiting state approval) for reducing hydrocarbon emissions and increasing generation by renewables. But, he wrote in an email, “Tri-State supported House Bill 25-1040,” and continued, “Nuclear will continue to be considered through our future electric resource planning process, to determine the best mix of generation for our members.”

Closer to home, Holy Cross Energy (HCE) also has no plans to implement nuclear generation, which Jenna Weatherred, HCE’s vice president for member and community relations, told The Sun, “is a question for our board [of directors]. We have not discussed nuclear power as a specific option for HCE with them.” Noting, however, that the company had just issued an “all-source request for proposals,” she explained, “If we were to receive a proposal for nuclear power that is safe, reliable and offered at a competitive price, I am sure our board would be interested in reviewing the proposed project.”

Concerns and opposition

While the actual generation of electricity using nuclear power certainly can be considered “clean energy” under the state definition, many have pointed out the importance of understanding the entire nuclear fuel cycle. Two of the most outspoken voices in Colorado are mining activist Jennifer Thurston of Paradox, in the southwest corner of the state, and Jeri Fry, a founder and co-director of Cañon City-based Colorado Citizens Against Toxic Waste (CCAT). Each spoke recently with The Sun.

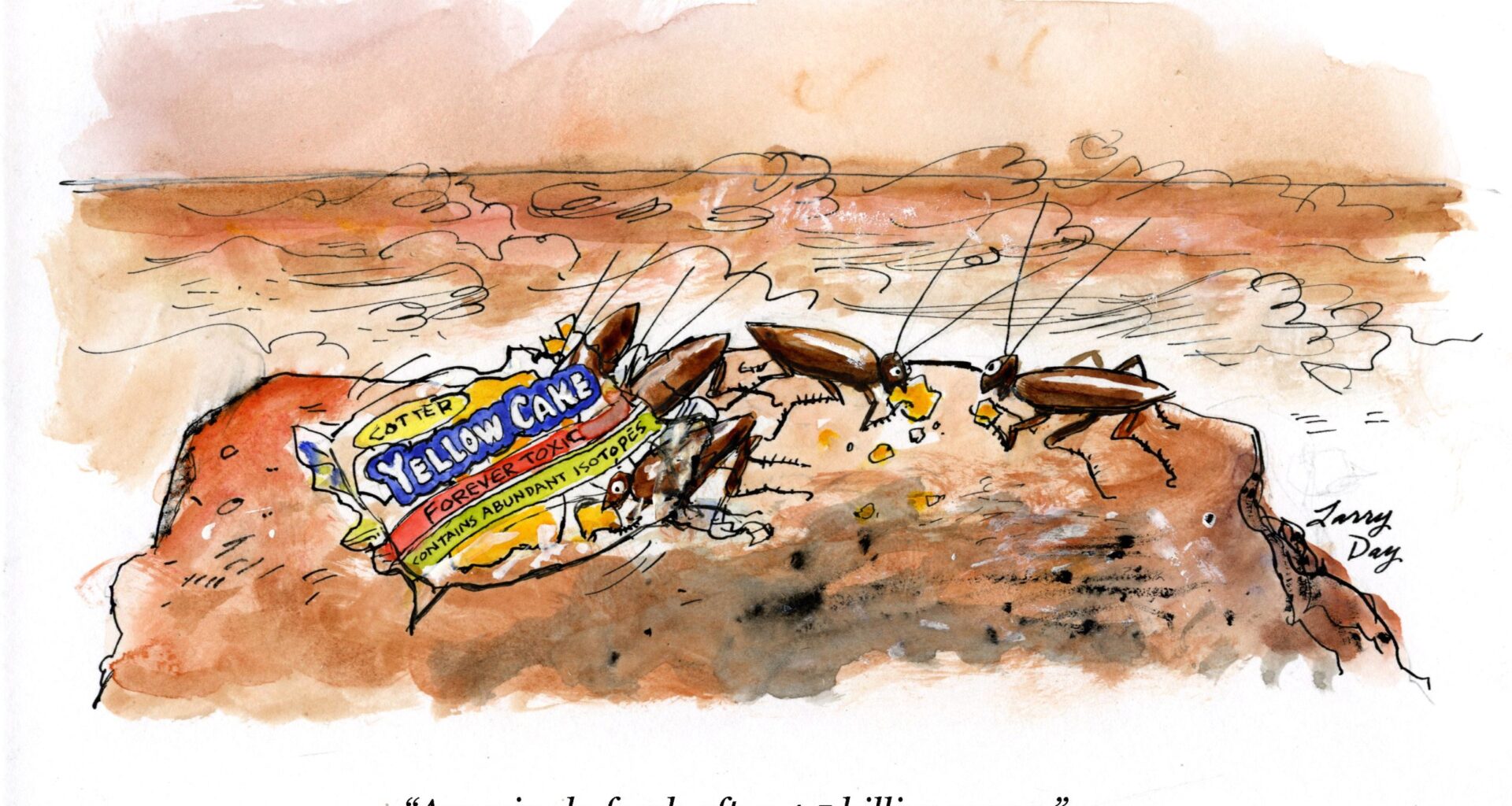

Fry began by noting the half-life of the most abundant uranium isotope, U-238, is 4.5 billion years — i.e., the approximate age of Earth — essentially, forever toxic. The less-abundant but fissile U-235 used in reactors is 700 million years. Fry’s word for the front end of the nuclear-fuel cycle (ore mining and milling into what is called yellowcake): “filthy.”

She should know. Her father was the lead chemist at Cotter Corporation in Cañon City, one of the mills that produced yellowcake. He blew the whistle on Cotter’s unsafe practices. The mill and surrounding area were declared a Superfund site in 1984; but to date there has been no cleanup, and the area remains highly contaminated with millions of tons of radioactive waste. Fry testified against HB25-1040 in the state legislature and said to The Sun, “We must insist that [those promoting nuclear power] look at the entire nuclear cycle; you can’t just be looking at reactors.”

Thurston lives close to scores of abandoned uranium mines, worked during “the heyday of the Cold War” in the 1950s and ’60s. Generally, those sites remain contaminated and radioactive, many of them near Native American communities. She told The Sun, “We really don’t have regulations in place to protect us” from mining practices, and those that do exist “are getting snipped and slashed.”

There is also the issue of handling and disposing of nuclear waste, including from processing operations and spent nuclear fuel. As the CCAT website points out, “Between 1951 and 1975 the United States had no policy for nuclear and radioactive waste disposal.” Much of the contamination at the Cañon City site is waste brought in from elsewhere that was improperly handled. Commenting on the renewed interest in nuclear power, Fry said, “We’re hurtling into untested territory,” continuing, “We have so many better choices with renewables.”

On that last point, Lauren Suhrbier, director of strategic development at Clean Energy Economy for the Region, wrote in an email, “We have been promoting geothermal development, which is possibly competing against an SMR for redevelopment at the Craig [plant].” Noting that the cost for installing geothermal compared to an SMR is essentially the same, she asked, “Why would ‘we’ (as State regulators and legislators) not be promoting that first?”