Since 1944, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been center of global financial stability. The organisation’s primary goal is to maintain monetary cooperation, to stabilize international trade, and to achieve sustainable economic growth amongst its members.

However, the IMF has often been criticised for crisis management approaches that not only deepen debt dependency in developing nations but also rekindle debate around the relevance of its policy prescriptions. Yet, as the international economic order becomes more multipolar, the IMF as a global financial governance authority is increasingly contested.

The Debt Dilemma: Relief or Leverage?

The IMF was created to provide financial support to countries which were unable to pay their international bills. Lending money to stabilise economies has been the most prolific role of the IMF. It has helped countries avert financial collapse, sparked temporary growth. But this aid has been provided with the condition on austerity, strict fiscal discipline, and structural reforms of policies that may give short term help but carry long-term social and economic burden.

IMF-dependent countries often get caught in a debt cycle. In return of funding, the IMF adopts harsh conditions such as opening up the markets, privatisation of state-run firms and fiscal tightening. These conditions can suppress local entrepreneurship, widen inequality, and impose disproportionate burdens on the most vulnerable populations. The IMF may provide temporary respite, but many countries have to contend with the implications of IMF conditions long after they have repaid the loan.

Erosion of Trust: The IMF’s Struggle to Adapt in a Changing World

The IMF’s governance structure is reflective of a post-WWII order that is out of vogue with the realities of the 21st century. As high-income countries hold more than 85% of the voting power, the poorest countries have very little to say institution in determining the course of their economies. This democratic deficit breeds resentment, particularly in the Global South, where the IMF is increasingly seen as an instrument of geopolitical influence rather than a neutral financial partner.

Argentina is a particularly salient example of the controversial role that the IMF has played, one that has shown repeated economic crises despite decades of attention from the IMF. The IMF’s largest-ever bailout — for $ 57 billion — was approved in 2018, only for the country’s economy to tumble into recession, inflation to climb over 50 percent and for poverty to cross its limit. Many experts criticised the IMF’s insistence on fiscal tightening and subsidy cuts during Argentina’s economic fragility, arguing that such measures would further depress domestic demand and deepen the recession. Far from stabilising Argentina, the IMF exposed the limitations of the country.

A Parallel Path: The NDB’s Challenge and the IMF’s Opportunity

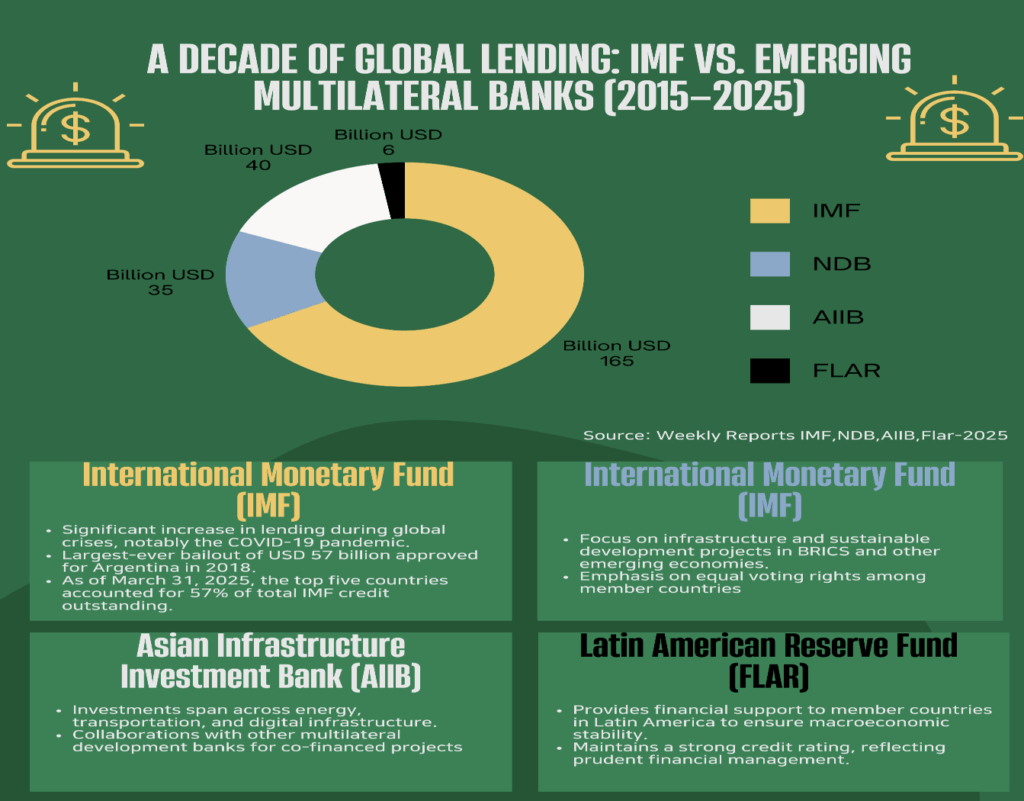

In recent years, alternative financial institutions like the New Development Bank (NDB), formed by the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), have become key rivals to IMF hegemony. NDB provides infrastructure and sustainable development funding with fewer hard and fast conditionalities than IMF loans. Its operating model promotes in equal voting rights, respect for sovereignty, and prioritisation of development. The NDB is not only a financial alternative to the IMF’s rigid framework but also a political option for countries weary of Western-centric governance.

The increasing attractiveness of such institutions as the NDB, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and regional alternatives like the Latin American Reserve Fund (FLAR), indicates a shifting balance in global economic governance. This global recalibration is not just about new banks—it reflects a broader demand for development financing that respects national priorities and regional contexts.

What Lies Ahead: Reform or Redundancy?

The IMF is at a crossroads, as global economic power shifts towards new centres of influence. Alternative institutions such as the NDB and AIIB are not merely a rebuke of austerity; they are calls for financial governance that is more inclusive, equitable and better aligned with the wide-ranging developmental requirements of the Global South. The IMF’s model in the mid-20th century, no longer fits the geopolitical and economic realities of the present era.

For the IMF to remain relevant, it needs far-reaching reform—from governance to decision-making to conditionality. Reforms must ensure broader representation, reduce the dominance of a few nations, and allow borrowing countries a greater say in shaping their own economic futures. By doing so, the IMF can turn disharmony on debt and development into harmony for global financial stability. In a rapidly evolving multipolar world, only by becoming more inclusive, responsive, and development-oriented can the IMF restore its legitimacy and global trust.

Sources

International Monetary Fund (IMF).

“What is the IMF?”

https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-at-a-Glance

The Guardian (2019).

“Argentina’s economy worsens despite IMF’s biggest-ever bailout”

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/aug/13/argentina-economy-imf-bailout-inflation

Brookings Institution (2021).

“A new direction for the IMF: Rebalancing global governance”

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/a-new-direction-for-the-imf/

World Economic Forum.

“BRICS bank: What is the New Development Bank and why does it matter?”

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/07/what-is-the-new-development-bank/

Al Jazeera (2022).

“Sri Lanka turns to IMF amid worst economic crisis in decades”

https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2022/3/15/sri-lanka-imf-bailout

Center for Global Development.

“AIIB and NDB in a Multipolar World: Challenging the Bretton Woods Legacy”

https://www.cgdev.org/blog/aiib-and-ndb-multipolar-world

Reuters (2018).

“IMF board approves $57 billion loan for Argentina”

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-argentina-imf/imf-board-approves-57-billion-loan-for-argentina-idUSKCN1N12JI