One of the driving forces behind the EU and India’s push to strengthen ties – China’s economic rise – is also one of the main impediments to deeper EU-India integration.

In recent months, European and Indian officials have done little to conceal the fact that, along with US President Donald Trump’s “America First” policies, a shared suspicion of Beijing is a key factor behind their push to deepen political, trade, and investment links.

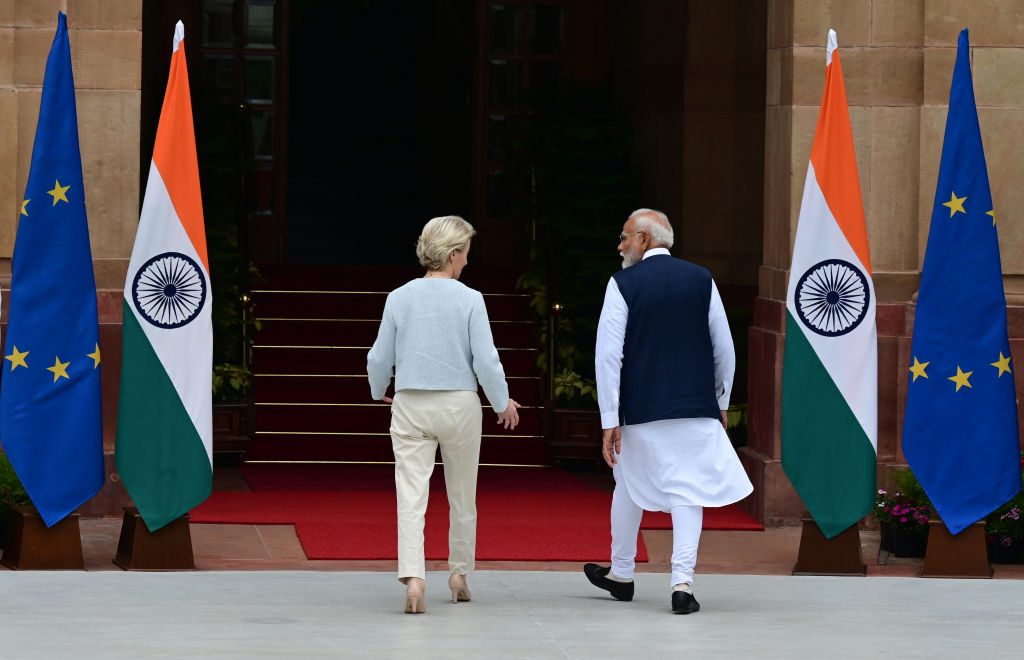

During a visit to New Delhi earlier this year – the first official trip by the new European Commission – Ursula von der Leyen said that “geopolitical and geo-economic headwinds” provide “a historic window of opportunity to build an indivisible partnership between Europe” and the world’s fifth-largest economy.

Similarly, Indian Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar told Euractiv earlier this week that European firms’ push to “de-risk their supply chains” should prompt both sides to deepen trade ties. Brussels and New Delhi aim to clinch a long-stalled free trade deal by the end of this year.

Analysts, however, warn that Europe’s push to reduce its strategic dependence on Beijing by pivoting south faces numerous obstacles, including India’s relatively low industrial development, high levels of protectionism, and overweening bureaucracy.

“Can India replace China? The short answer is no – at least not in the short term,” said Niclas Poitiers, a research fellow at Bruegel, a Brussels-based think-tank.

That assessment is corroborated by a plethora of recent studies, forecasts, and data.lation

EU-India trade is currently just a fifth as large as annual EU-China exchanges in goods and services, despite having surged by more than 90% to €180 billion over the past decade.

India overtook China to become the world’s most populous nation two years ago, but India’s GDP in dollar terms remains well below a quarter of the size of its northern neighbour.

Goldman Sachs has also estimated that India’s output will still be smaller than China’s in 2075, even though it is rapidly outpacing Beijing’s current rate of growth.

‘China is too well entrenched’

China is unlikely to relinquish its status as the world’s sole manufacturing superpower anytime soon. The world’s second-largest economy currently accounts for around 80% of all solar panel production and roughly 90% of all processing of so-called “rare earths”.

According to the United Nations Industrial Development Organization, India’s share of global industrial production will rise from just under 2% today to around 3% by 2030; China’s portion, meanwhile, is expected to surge from 30% to 45%.

Sony Kapoor, CEO of the Nordic Institute for Finance, Technology and Sustainability, said that New Delhi’s decade-long push to boost domestic manufacturing through Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s much-vaunted “Made in India” initiative is unlikely to threaten China’s global industrial dominance.

“I don’t think India will be the next manufacturing leader in the world,” he said. “It’s too late – China is just far too well entrenched.”

Kapoor, a native of India, added that “there are several very good reasons – commercial, financial, security, and geopolitical – to deepen the EU-India relationship”, pointing to the potential mutual benefits of integrating millions of well-educated, under-employed Indians into economically productive services in the world’s largest democracy.

“But if this [EU-India integration] is being done from the EU’s perspective primarily as a way of de-risking manufacturing supply chains away from China, then the EU is likely to be disappointed,” he said.

Analysts warn that, even if the EU were to seal a fully-fledged trade deal with India by the end of 2025, this would still fail to address New Delhi’s high tariff levels with third countries, which limit its ability to source key components and move up the global value chain.

Poitiers, the Bruegel research fellow, said that India’s development model is importantly distinct from China’s, insofar as the latter is more open to sourcing components for its manufactured products from other countries in East Asia.

“The trillion dollar question is: Is India finally ready to open itself up to the world?” he said.

‘Two different galaxies’

New Delhi’s deeply entrenched protectionism has also prompted trade talks between India and the EU to hit several roadblocks over the past few months, according to EU and industry officials.

“It is quite obvious that we’re not going to be able to finalise a fully fledged free trade agreement à la New Zealand with India in the next 10 months,” Christophe Kiener, the bloc’s chief negotiator, told MEPs in March, adding that the two sides approached some trade issues from “two different galaxies”.

Agriculture remains the biggest stumbling block. Brussels wants better market access for its food and drink products, but India – whose agricultural sector accounts for 16% of its GDP and employs nearly half of its workforce – is insisting on maintaining steep import levies.

One of the EU’s top priorities is to force India to slash its 150% duty on spirits. Here, there are signs that New Delhi’s stance might be softening: The country recently cut tariffs on UK gin and Scotch from 150% to 40% over 10 years, with similar moves for US bourbon. An industry source also told Euractiv the negotiations over spirits are now “pretty positive”.

Several major food-related points of contention remain, however.

India has reportedly put dairy – a major EU export – off the table for negotiations. EU Commissioner for Agriculture and Food Christophe Hansen has warned that if India won’t open its dairy market, Europe could also reject increasing quotas for sugar, a key Indian export. But dairy industry sources remain hopeful. “We trust there will be a chapter on dairy,” one told Euractiv.

Automobiles are another major flashpoint. The EU is pushing for zero tariffs on car imports – a bold demand given New Delhi’s current 100%+ tariff.

One potential sign of hope is the fact that the UK was able to agree to a 10% levy on car exports in its recent trade agreement with India. But opening up to the 27-country bloc, especially to Germany, a car-making powerhouse, could pose a major threat to India’s domestic car industry, in particular its growing electric vehicle sector.

The final, critical point of contention is the EU’s green rulebook. India wants special treatment under landmark climate policies like the carbon border tax (CBAM), which could cause some Indian exports to the bloc to face steep levies.

Jaishankar told Euractiv this week that India still has “very deep reservations” about CBAM. “We’ve been quite open about it,” he added.