The Annual Report of the Bank of Italy sheds light, with data in hand, on the real trend of the labor market and the dynamics of wages. It is not true that precariousness has increased

May 30 is the day on which the Report of the Bank of Italy of the previous year and the Governor in office – like an officiating priest – presents his ideas in the presence of the country’s elite Final houghts. Solemn rites always have fixed dates that enhance their authority. In fact, the Governors of the Palace with the palms of Via Nazionale on May 30 do not express debatable opinions but speak ex cathedra. The Final Considerations are a political summary document, while the Report is much broader and addresses all the economic and social aspects of the year to which it refers. In his speech Fabio Panetta outlined the complexity of the scenarios in which “we must prepare to navigate these uncertain waters, without giving up our values and without being left behind”.

And in particular, according to the Governor, “after the shock of the global financial crisis and sovereign debt, we are seeing signs of change: in manufacturing and services, in the financial sector, in the functioning of public administrations, in research capacity. These are signs of vitality that should not be lost. They are not accomplished results – continued Panetta – but they represent real progress. It is a concrete basis on which to build, engaging in reforms, fighting vested interests, offering prospects to young people. We have the responsibility and the opportunity to do so” he concluded. Oh dear! Where has the country gone, at the mercy of poverty and precariousness that is described by the political and trade union opposition with meticulous insistence and according to immutable certainties that allow different opinions? Where employment is growing but wages are too low, so much so as to induce young people to immigrate (700 thousand in the last ten years)?

The wage gap has not been completely closed but increased employment improves family incomes

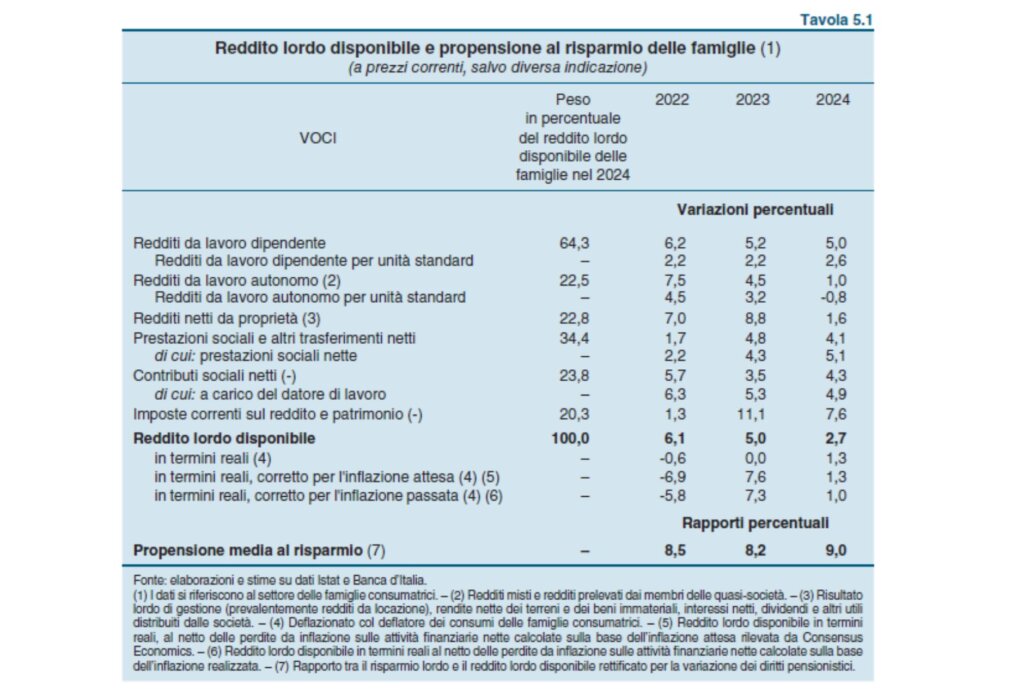

Looking for the key points of the political debate in the Report, one can find some surprises, referring to topics that deviate from the current narrative, the only one considered politically correct. For example, the wage gap has not yet been fully recovered, but the increased employment (which is still not comparable with the rates of other countries, especially with regard to women’s work) has contributed to the improvement of family incomes. In 2024, in Italy, household disposable income continued to expand, although less than in the previous year due to the strong deceleration of income from self-employment and property; on the other hand, the trend of income from dependent work remained strong, driven by both the dynamics of employment and that of wages; the latter, however, in real terms, remain lower than the levels of 2021. Public support measures continued to be aimed mainly at low-income families and those with children, for whom the risk of poverty is greater.

Thanks to the marked reduction in inflation, purchasing power has started to grow again after the slight contraction of the previous two years. However, the increase in consumer spending has remained moderate, held back both by the incentives to save resulting from the historically high levels of real interest rates and by the deterioration of unemployment expectations. According to a specific analysis, the latter would only marginally reflect the fears associated with the impacts of artificial intelligence on the labor market. The savings rate has started to increase again, settling at higher values than those before the pandemic.

On the other hand, the growth of income from employment remained consistent, driven by both employment and wage dynamics, even though in real terms the latter are still far from the 2021 levels (see the table, ed). Social benefits also continued to expand, thanks to the pension component. After contracting in 2022 and stagnating in 2023, household purchasing power started to rise again (1,3 percent), benefiting from the sharp reduction in inflation. Real income increased even after taking into account the erosion of the value of net financial assets due to inflation. As in 2023, a strong contribution to household income came from the increase in employment.

According to the Bank of Italy’s calculations of the Istat Labour Force Survey data for the first three quarters of 2024, among households whose reference person is under 65 and in which there are no pensioners, the share of families without workers has further decreased, especially in the South (to 23,6 percent from 24,5 in 2023; to 9,7 percent from 10,0 in the Center North), and the percentage of those with two or more working adults has increased. In 52,6 percent of the families considered, there is at least one woman with a job, a higher value than in 2019 (51,3 percent), in line with the trend in the female employment rate.

In 2024, public income support transfers continued to be mainly aimed at low-income households and those with dependent children, who are at higher risk of being in absolute poverty. The Inclusion Allowance (AdI) replaced the citizen’s income and the citizen’s pension for families with minors, disabled members, those over 69 years of age or in disadvantaged conditions; for those of working age but not eligible for access to the AdI, the support for training and work (Sfl) was activated instead. According to INPS data, last year 752.000 families received at least one monthly payment of the AdI – for an average amount of 621 euros per household – and 130.000 individuals benefited from at least one monthly payment of the Sfl. The latter had a much lower level of participation than the Government had expected and starting from 2025 its rules have been partially modified, increasing the number of those entitled, providing for the possibility of renewal and increasing the amount of the subsidy (from 350 to 500 euros per month).

The single allowance for 6,4 million families

The Single and Universal Allowance (Auu) was received in 2024 by almost 6,4 million families for approximately 10 million children under 21 or with serious disabilities, equal to more than 90 percent of the reference group (a share similar to that of the previous year). Mainly due to inflation adjustments, the average monthly amount for each beneficiary (172 euros) increased by approximately 17 percent compared to 2022 (the year the measure was introduced), an increase lower than that estimated for maintenance costs. With the aim of supporting the birth rate, from 2025 a one-off payment of 1.000 euros is expected for new births in families with an ISEE lower than 40.000 euros (which corresponds to approximately 40 percent of the average annual amount of the Auu received for each child by these families). In 2024, social bonuses for electricity and gas continued to be paid to families with an ISEE below 9.530 euros (20.000 euros in the case of more than three children), while those with an ISEE between 9.530 and 15.000 euros, who had accessed it in the previous year, were excluded from the measure. For 2025, the Government has introduced a further extraordinary contribution of 200 euros to be discounted on the electricity bill of families with an ISEE below 25.000 euros (Legislative Decree 19/2025). It is estimated that this subsidy could concern approximately 30 percent of all families and that its amount is significant when compared with the increase in average annual expenditure for utilities between 2020 and 2022, the year of peak energy prices (just under 250 euros, taking into account the discounts provided for by existing bonuses).

At the end of 2024, household net wealth (the value of financial and real assets net of liabilities) increased to 11.700 trillion euros; it remained almost stable compared to disposable income, at 8,3 times.

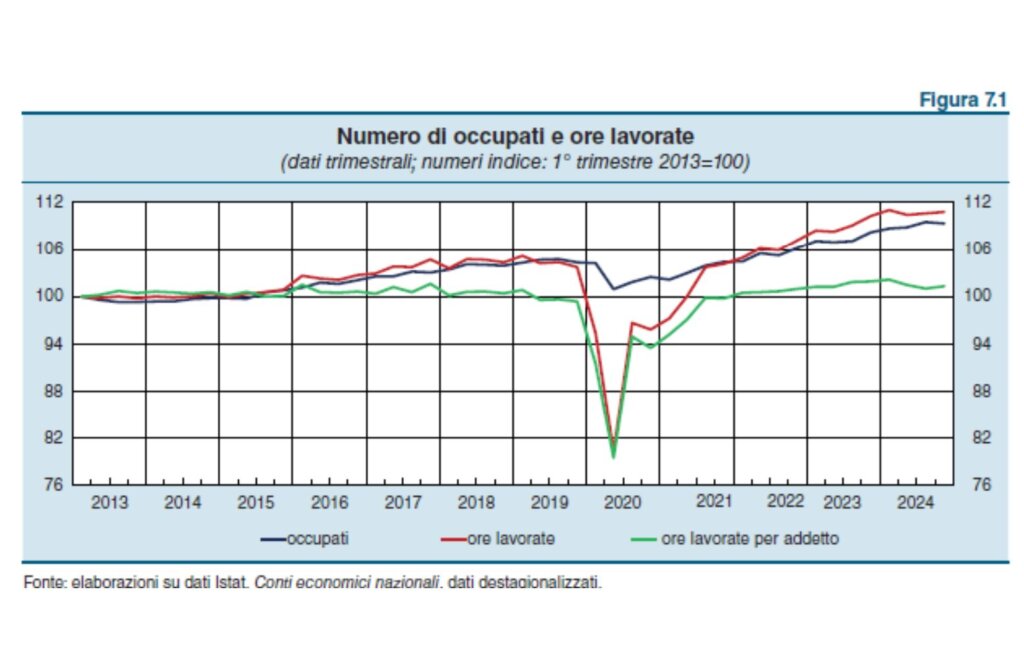

Labour market: employment slows but grows faster than GDP

As regards the labour market, in 2024 employment, although decelerating, continued to grow faster than GDP. The demand for labour still benefited from the moderate wage dynamics of the last three years, which made labour relatively cheaper compared to other production factors. The expansion of employment affected essentially all sectors and was concentrated among permanent positions and older workers; labour demand weakened compared to 2023 especially for young workers and for temporary contracts, which are generally more sensitive to the economic cycle.

The participation rate remained at the high levels reached in 2023, thanks to the continued increase in labor supply among workers aged 55 and over, which offset the decline observed among younger workers. Immigration partially offset the decline in the Italian working-age population; foreign workers mostly work in jobs characterized by less stable contracts than Italian-born people and in low-wage positions. The unemployment rate fell to its lowest value in the last 17 years.

The number of vacancies in companies compared to the total number of jobseekers, an indicator of the level of competition for worker recruitment, has increased, approaching the European Union average. According to preliminary estimates, employment has started to grow markedly again in the first months of 2025, also supported by investments related to the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP).

In a context of weak economic activity, employment slowed in 2024: the number of employed persons and hours worked increased by 1,6 and 2,1 percent, respectively, against 1,9 and 2,5 percent in 2023. Growth was driven by permanent employment, while fixed-term employment, which is more affected by the economic cycle, declined. Self-employment increased to a more limited extent, remaining below pre-pandemic levels.

The increase in permanent employment positions mainly affected the population aged 50 and over, due to both demographic aging and the slowdown in the outflow from the labor market, partly due to past pension reforms. According to INPS data, the growth in permanent contracts was also favored by the low rate of dismissals and the high number of transformations of existing temporary contracts. On the other hand, fixed-term and youth hiring decreased.

The number of vacancies in companies has slightly decreased, although it remains high compared to the years before the pandemic. In addition to the stronger economic dynamics of sectors such as construction and accommodation and catering, in some sectors there are still difficulties in recruiting workers with adequate skills. The vacancy rate is high in sectors with a strong demand for graduates, such as ICT and professional services. The reduction in the number of vacancies has been less intense than that of the unemployed and the ratio between the two quantities, which captures the degree of competition between companies in attracting workers, has therefore continued to increase, approaching the EU average values.

The growth of contractual wages in the non-agricultural private sector intensified in 2024 (to 4,0 percent, from 2,2 in 2023), contributing to the recovery, albeit still partial, of the loss of purchasing power caused by high inflation in the period 2021-233. The acceleration of contractual minimums affected almost the entire private sector: in industry excluding construction, growth was 5,1 percent (from 3,4 in 2023), mainly reflecting the adjustment to past inflation dynamics envisaged by the metalworking sector contract4, which affects over 2 million workers; in private services, the increase, driven by renewals in the credit, trade and tourism sectors, was 3,5 percent (from 1,3). In 2024, in construction – whose contract expired in June 2024 and was renewed only in January 2025 – contractual wages decelerated (to 1,2 percent on annual average, from 1,8 in 2023).