“Nominication” is a Japanese word for building closer relationships with colleagues through drinking (nomi) and communicating. Although its heyday has passed, it remains a recognized part of work culture.

Picture the scene. Employees hold glasses and call out “Kanpai!” (Cheers!) in an izakaya pub near their workplace. There is food, but the focus is on drinking until they feel relaxed enough to share thoughts and opinions freely that they would feel hesitant to say aloud under ordinary circumstances.

The Japanese word nominikēshon (nominication) is a portmanteau of nomi, a form of the verb “to drink,” and the English word “communication.” It is a recognized part of Japanese work culture, seen at nomikai or “drinking parties,” where alcohol is thought to be a way of building closer relationships.

The classic party is the bōnenkai to “forget” the year at its end—or its troubles, at least. Other common gatherings take place at the start of the year, or when employees leave or join the company, but they can happen for any number of reasons. They might be held at an izakaya or restaurant with large numbers, or a few people might get together at the counter of a local drinking establishment. Participants often pour drinks for each other from shared bottles—with the company hierarchy in mind, bosses tend to receive this favor—and food is also portioned out.

Many people consider it polite for the label of a beer bottle to face upward when pouring for others. There is still a general expectation at many companies that lower-ranking employees should take responsibility for pouring drinks and serving food. (© Pixta)

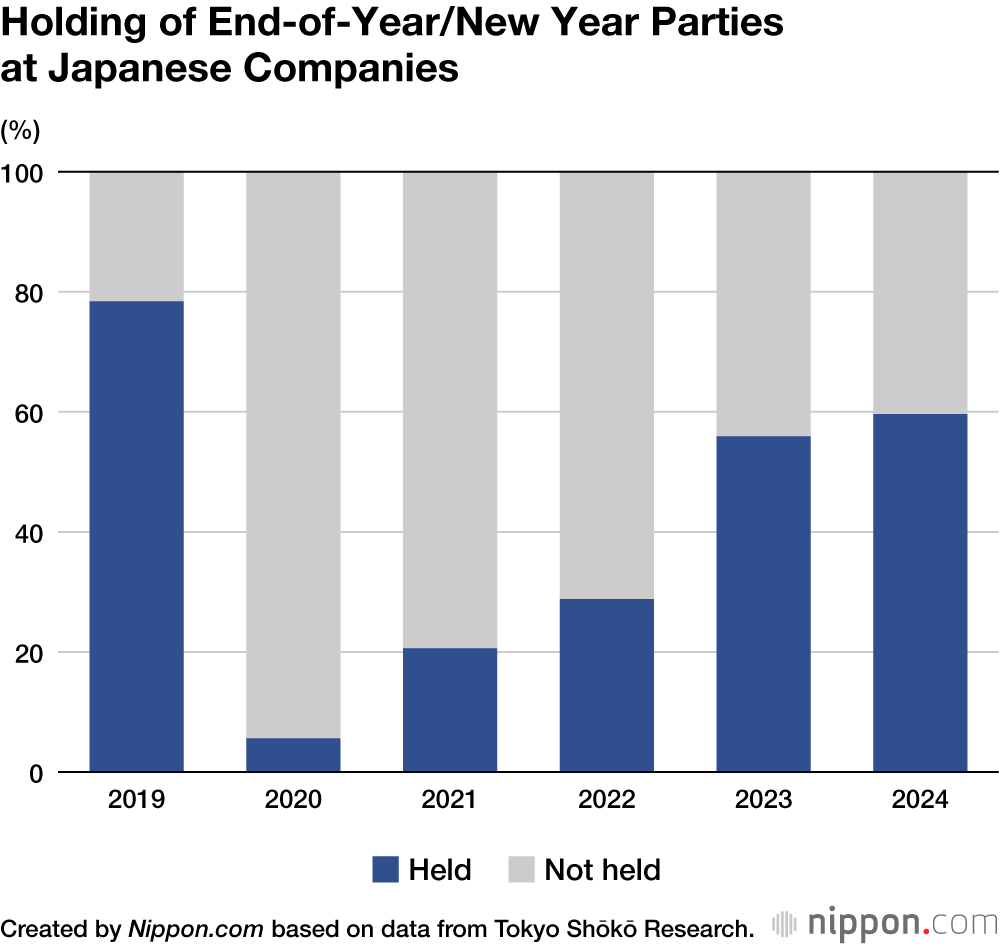

However, this corporate culture is rapidly changing. A 2024 survey by Tokyo Shōkō Research found that only 59.6% of companies held end-of-year or New Year parties, which was almost 20 percentage points lower than 2019, before the spread of COVID-19. Reasons like a lack of demand or increased expressions of opposition by employees mean that drinking parties have not fully recovered even after the end of pandemic restrictions.

In other surveys, employees’ top reasons for why they do not like “nominication” are that they feel they cannot truly relax, and that it seems like an extension of work. Oguchi Yutaka of the NLI Research Institute says that the pandemic led to increased diversification in how people work, along with more pronounced separation between their jobs and private life.

Nominication and Its Discontents

The National Tax Agency found that Japan’s per capita alcoholic drink consumption was 75.4 liters in fiscal 2022, which was a 25% drop compared to 30 years earlier. Young people, in general, are drinking less, leading to a perceived tendency for them to want to stay away from drinking parties.

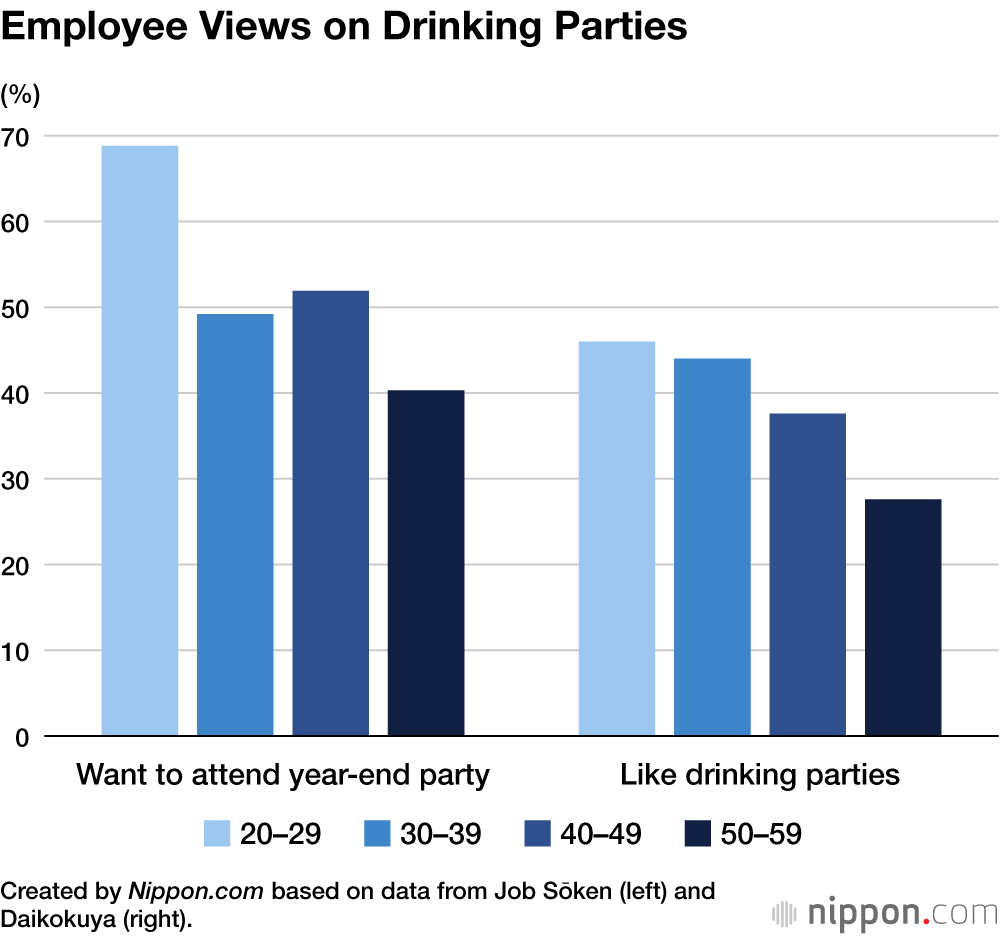

However, a 2024 survey by Job Sōken found that older people were more likely to be unenthusiastic about nomikai. Among employees in their twenties, 68.8% said they would like to attend a year-end party, far ahead of those in their forties (51.9%) and fifties (40.3%). Another survey in 2023 by Daikokuya turned up similar results, with 46% of respondents in their twenties and 44% of those in their thirties saying that they liked work drinking parties, compared with 37.6% and 27.6% for employees in their forties and fifties, respectively.

With many people in their fifties having reached the management level, perhaps they are concerned about the risks that workplace parties involve. If they get carried away with drinking, they might go too far and instigate a bullying or sexual harassment incident. There is even the umbrella term “alcohol harassment” for unwelcome behavior related to drinking.

A survey by Persol Research Institute found that almost 80% of respondents considered criticism for not attending drinking parties or not pouring drinks to be harassment. Around half thought it was harassment if someone ordered a beer for them without asking. The need to consider behavior at parties, as well as health issues, is making it more difficult to even invite people in the first place.

The possibility of harassment issues arising has become a concern at drinking parties. (© Pixta)

In February 2024, the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare published its first guidelines on the health risks of drinking. This stated that consuming 20 grams of alcohol (for example, in a 500-milliliter can of beer) increases the risk of colorectal cancer. Greater concern about the connection between drinking and health problems can be seen among all generations.

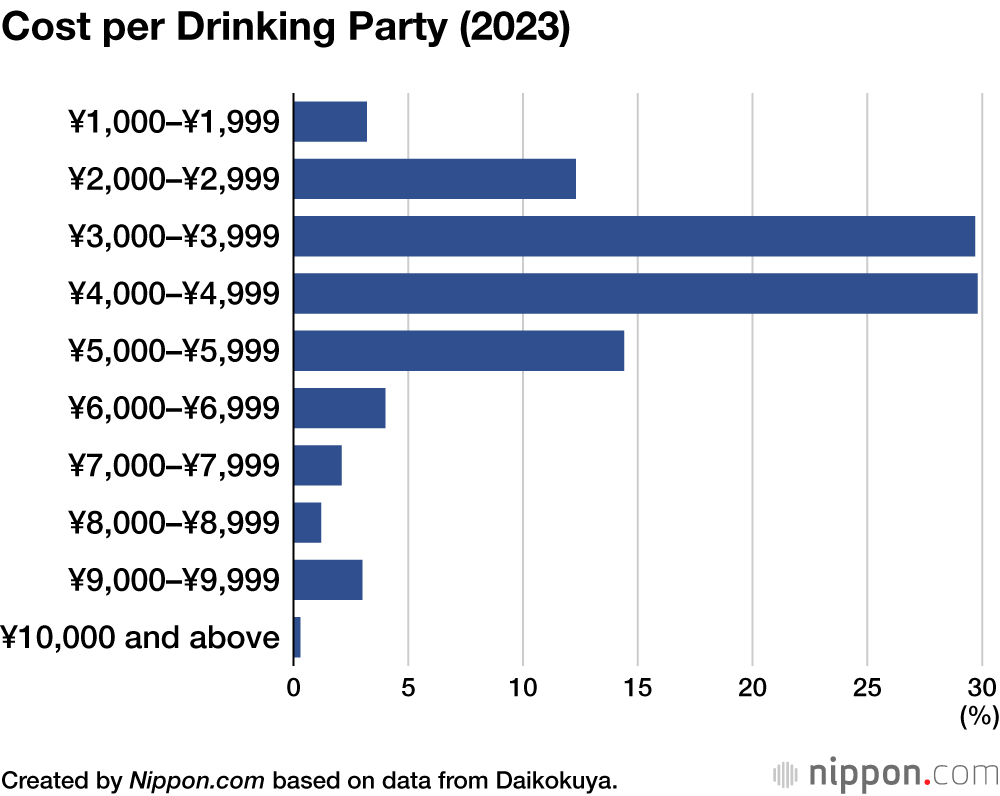

According to the Daikokuya survey, respondents attend an average of 17 annual work drinking parties, spending an average of ¥4,237 each time—adding up to ¥6,002 per month. The trend of rising prices since 2024 may be another reason to give parties a miss, banking that money for other needs.

Many workers in their twenties became adults during the pandemic and have struggled to communicate with their peers and older colleagues. This is the reason for the general tendency to want to meet up face to face with others. In the Job Sōken survey, the most popular reasons for wanting to take part in a drinking party were to deepen friendships with colleagues, to have an opportunity to talk to others in person, and to build relationships with bosses. In the free response section, one opinion stated was that remote work had highlighted the benefits of meeting and talking face to face. Maybe as nominication becomes less common, people will start to recognize its value again.

Past and Future

Since ancient times, alcohol has been a means of building connections in Japan, playing an important role at key ceremonies in people’s lives. On its website, the Japan Sake and Shōchū Makers Association describes how drinking alcohol together forms a symbolic bond, as when a bride and groom share sake.

Local townspeople are depicted drinking together in this picture from the Edo period (1603–1868). (Courtesy National Diet Library Digital Collection)

Workplace drinking parties became common in Japan and seen as a way of improving communication in the 1960s, during the country’s high-growth period. The word “nominication” first appeared in the media in the 1980s. A 1984 article in the Asahi Shimbun featured an interview with a manager at a major company who talked about receiving unexpected advice from employees while drinking and getting the perspective of young people.

Companies still feel such gatherings to be beneficial. An HR Research Institute survey found that around 60% of firms identified internal problems with communication. The most popular answer for effective ways of dealing with this was to hold or subsidize parties where employees drink and eat together.

New takes on drinking establishments may shape the future of nominication. Since 2022, Asahi Breweries has run the Sumadori Bar in Shibuya, which takes its name from an abbreviation of “smart drinking.” This offers a wide range of nonalcoholic and low-alcohol beverages, targeting nondrinkers who enjoy the social aspects of bars and others who want to take it easy. Other drink makers are also increasingly taking notice of this market, which is growing among young people especially.

The Sumadori Bar in Shibuya, Tokyo, offers drinks with three levels of alcohol content: 0%, 0.5% and 3%. (© Tanaka Ruiko)

While employees increasingly value their private lives and young people drink less alcohol, the demand among both companies and many workers for better social ties with their colleagues means that nominication is likely to continue, even if it changes along the way.

(Originally published in Japanese on May 20, 2025. Banner photo: Japanese workers enjoy a drink together. © Pixta.)