Extraction of fossil coal © Shutterstock

Decarbonization in Europe is progressing at different speeds. The challenge is to transform coal-based economies through investment and retraining. Asturias, in Spain, shows the way: existing infrastructure can be repurposed for new uses

(Originally published by our project partner El Orden Mundial )

What began as the European Coal and Steel Community is disengaging from the mineral that for decades heated homes, powered industries and defined regional identities. The European Union’s energy transition involves leaving behind not only an energy source, but also a way of life rooted in many regions. Specifically, 31 territories in eleven Member States are covered by the Coal Regions in Transition Initiative (CRiT ) implemented in 2017 to help mitigate the social consequences of the transition to a green economy.

Coal generates almost twice as much CO₂ per unit of energy as natural gas, and is responsible for 40% of global emissions . Despite the progressive decline, in the EU it still generates 13% of electricity . The message is clear: the EU wants to become the first region in the world to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, with a 55% cut already targeted for 2030.

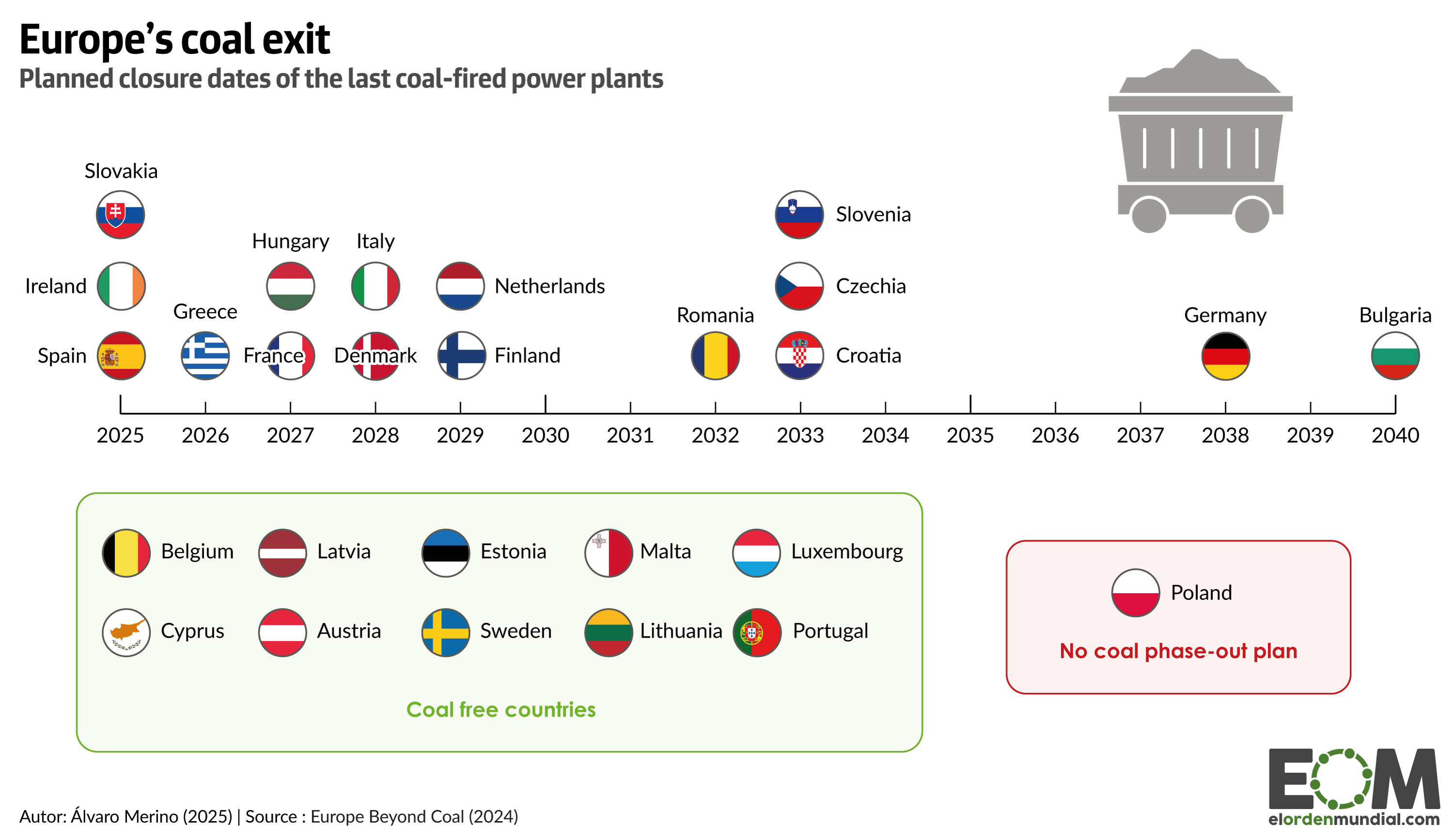

However, the coal phase-out is a clear example of the uneven pace of decarbonization across the EU. Most of the Member States covered by the decarbonization initiative have committed to eliminating coal from their energy mix by 2030, including Spain . But there are three laggards: Germany (2038), Bulgaria (2040) and Poland, which has no official date set. In addition, up to 208,000 jobs in the EU are directly related to coal activity, most of them in the mining sector, and are therefore compromised by the green transition.

European decarbonization relies on Cohesion Policy.This policy aims to reduce regional disparities, with a particular focus on rural areas facing industrial challenges or structural disadvantages — such as coal-dependent regions.

Until 2020, these regions had access to funds that supported everything from energy efficiency to worker training , or programs that contributed indirectly . That year, the Just Transition Fund (JTF) was finally created within the framework of the Just Transition Mechanism (JTM). It is the first specific instrument with a coordinated approach to support the regions most affected by the shift away from fossil fuels.

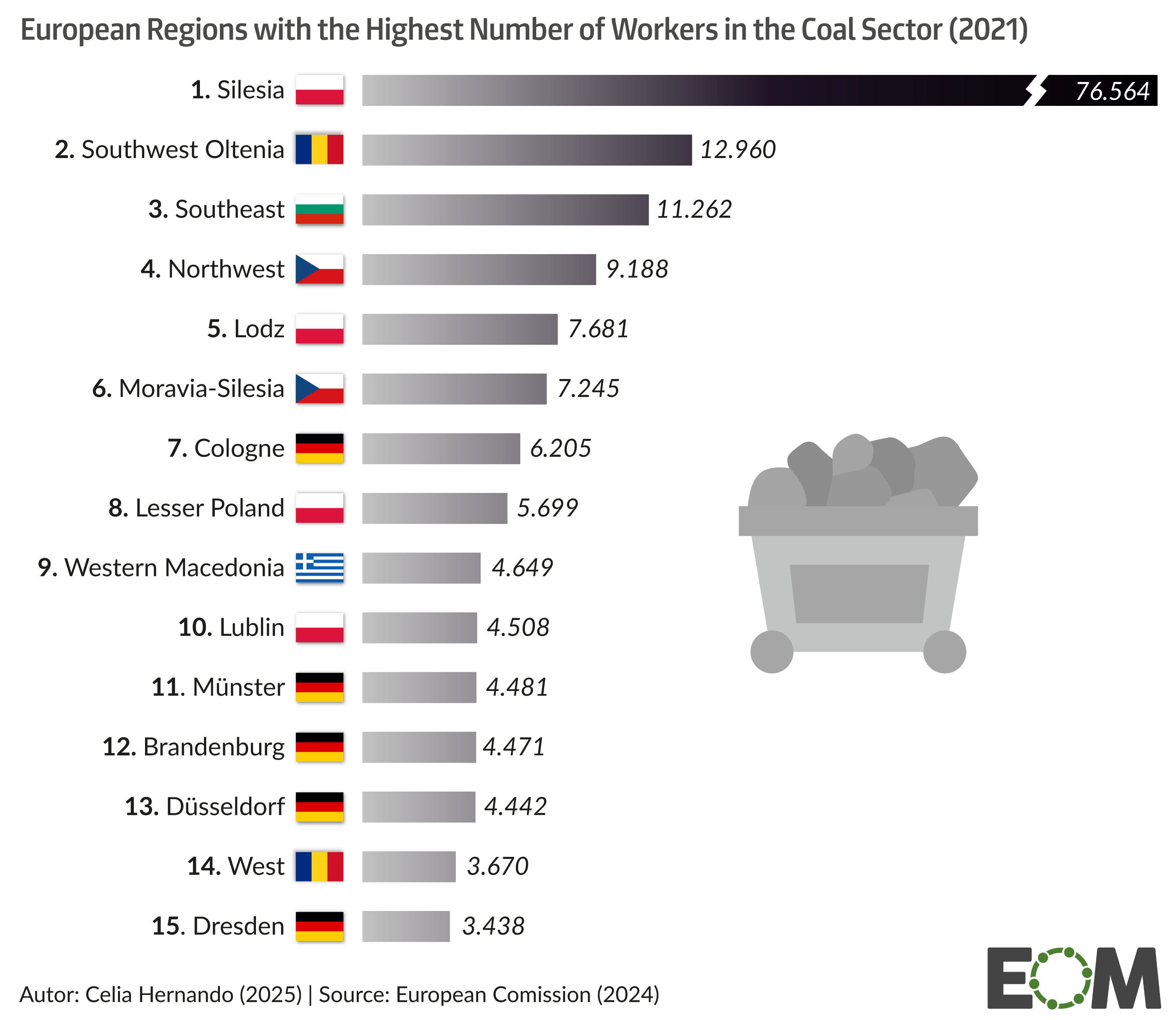

With a budget of 27 billion Euros for the 2021–2027 period, including national co-financing, half of the Just Transition Fund (JTF) is dedicated to diversifying local economies and improving the skills of workers in declining sectors . Poland will receive the most funds: more than 4.7 billion Euros, followed by Germany (3.7 billion), Romania (2.5 billion), the Czech Republic (1.9 billion) and Greece (1.6 billion). This distribution is not surprising: the Polish region of Silesia has the most workers in the sector, some 76,000, according to data from the European Commission. In addition, the regions likely to face the greatest economic slowdown due to an abrupt transition are Western Macedonia in Greece and Southwest Oltenia in Romania.

However, the fund does not cover the magnitude of the decarbonization challenge. The JTM mobilizes around 9 billion Euros per year, while in 2022 alone the coal sector generated 48 billion Euros between mining and imports, and an additional 110 billion Euros linked to electricity generation. In any case, the objective of the JTF is not to make up for the immediate economic losses resulting from the closure of mines and plants, but rather to encourage productive diversification, improve employability and guide the transformation of the territories. All of this, guided first by the state or regional authorities.

Challenges ahead for coal regions

A major challenge for the EU has been precisely to balance national autonomy with common action. This challenge also marks the green transition . European funds are designed to complement national actions, but the ability of Member States to take advantage of them varies. A German and a Romanian region, for example, are entitled to the same funds, but the German region has more resources, technical capabilities and fiscal room to implement the transition. The gap widens with national subsidies: in 2023, EU countries spent 61 billion Euros on renewable energy subsidies , but they were concentrated in countries with more fiscal capacity . The result is that the energy transition proceeds at different speeds, increasing inequality among EU regions.

By definition, just transition poses an ideal: transforming the energy model without leaving anyone behind. But in practice, companies have several options for carrying out the reconversion. Early retirement is a common route, but it does not suit all profiles. Young workers, especially those linked to mining, are more exposed to unemployment and an uncertain future. The success of the transition depends on creating stable and qualified employment in these areas to reconvert the local economy and avoid social turmoil: this requires public investment, private capital and a commitment to reskilling.

The EU will also need to carry out these policies within a more complex international environment. European rearmament is shifting priorities in public budgets, in some cases reducing the margin for financing green policies.

In addition, energy geopolitics has changed: abandoning coal seemed easier when Europe could rely on Russian gas. Now, the drive towards renewables is also creating new dependencies, such as on critical minerals from China. As a result, the EU will need to balance its climate goals with its pursuit of strategic autonomy.

On top of that, there is a democratic challenge: maintaining consistency in the message. If, in the face of a crisis – such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine – some countries return to coal or soften their climate targets, as Germany did, a contradictory message is sent to citizens. In territories suffering the closure of mines and factories without clear alternatives, the perception of abandonment grows. The transition is seen as an external imposition rather than a common project. This lack of consistency erodes confidence and fuels Euroscepticism, especially in regions that already felt forgotten. If the green transition is not seen as a key policy of the bloc—one that is fair, inclusive, and coherent—it risks losing political legitimacy.

New life for coal infrastructure

As of today, Europe cannot afford to dismantle all of its traditional energy capacity by 2030. However, there are opportunities to position coal-producing areas as leaders in Europe’s new green industry. One of the most promising paths is to reuse existing infrastructure—whether by adapting it to store energy, support other sources like solar or green hydrogen , or transform it for entirely different uses, such as this cultural center in the United States. This is a significant opportunity since coal-fired power plants and mines are often located in areas with strong electrical connections, rail networks, access to water, and a skilled workforce.

Asturias is an example of good conversion practices. This Spanish region, historically centered on mining and industry, is developing renewable energies as its alternative to coal. One of the projects underway is the Asturias H₂ Valley , in Aboño, which seeks to create an entire regional hydrogen ecosystem: from its production to its use in sectors such as transport or industry. Companies such as EDP, Enagás or ArcelorMittal -the world’s largest steel producer, with plants in Gijón and Avilés- are actively participating in the transformation. ArcelorMittal, for example, plans to use green hydrogen in its furnaces to replace coal and thus reduce emissions in steel production.

There are more territories with similar projects, such as Hamburg or the Konin district in Poland . Many are included in the list of Important Projects of Common European Interest , which seeks to attract and finance initiatives that promote economic growth, decarbonization and industrial competitiveness. Although Asturias, with just 2,000 workers in the sector, no longer has much in common with the situation in Eastern European regions, it has managed to avoid a sudden vacuum following coal’s decline. The Principality still faces structural challenges such as unemployment and demographic decline, but careful planning and cooperation among local, national, and European actors are laying the foundations for a new productive model.

These transitions are not limited to the coal sector alone. Other industries, such as automotive manufacturing, are undergoing similar transformations. The energy transition therefore presents a broader challenge: adapting entire sectors, safeguarding jobs, and addressing regional inequalities. In this context, the energy transition is fundamentally a political project, not just a technical one—and the transformation of coal regions could become a critical testbed for the success or failure of the entire European project.

Co-funded by the European Union. The opinions and views expressed are, however, those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.