For 80 years, Germany has done everything it can to stamp out all vestiges of Nazism. It has told itself and the world that it, and only it, could have meted out such horror. The notion of Sonderweg, the special path, is deeply embedded. According to this reading of history, Germans followed a straight line from Bismarck to Hitler. We Brits love to hear this kind of thing: those pernicious Huns.

We, by contrast, would never have succumbed.

But having had the dubious honour of spending the last few months immersing myself in Mein Kampf, which was published a century ago next week, I am more convinced than ever that we are deluding ourselves. The same blithe over-confidence applies to Americans (indeed pretty much anyone). We are all prone to the most dangerous propaganda, extremism and hate, no matter where we come from.

Before embarking on this assignment for a BBC radio documentary, I had never read Mein Kampf. No sensible person, apart from a history scholar, would have done. For me, it was a particularly unpleasant prospect given that my Jewish father fled Czechoslovakia shortly after Hitler had marched in and several members of his extended family were killed in the concentration camps.

In Germany, the book has been taboo, subject not just to legal copyright restrictions (new versions could not be printed), but also to social shame. However, from India to Turkey and beyond, it has done a healthy trade around the world.

It took me nerves of steel to plough through the more than 700 pages of this grubby work, 30 pages a night, with its endless distorted references to biology and race theory, with its warnings about miscegenation and the poisoning of good German blood. Much of it is predictable: a badly written mix of narcissistic autobiography and job application to lead Europe’s nascent fascist movement.

But, the main conclusion I drew from my research was that, just as Hitler’s odious book was based around a cut and paste (not that typewriters of the 1920s were capable of such things) of late 19th- and early-20th-century race-based ideology, much of what is appearing online today in the 2020s follows the same path. It is part of a continuum.

With the help of Dr Simon Strich, an academic from the University of Potsdam, I traced a direct line between many of the ideas contained in Mein Kampf to videos on current YouTube, popular podcasts and social media posts, many of them with millions of hits and clicks. From that, you can move to speeches from the likes of Hungary’s Viktor Orban, Italy’s Giorgia Meloni and (you guessed it), Donald Trump.

open image in gallery

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor meeting with Hitler in Munich in 1937 (PA)

Consider this: “They’re destroying the blood of our country, that’s what they’re doing. They’re destroying our country. They don’t like it when I said that. And I never read Mein Kampf. They said, “Oh, Hitler said that, in a much different way’.” That was Trump during an election campaign rally in December 2023. There are a number of other examples that I could have cited.

Then run alongside it the following: “The poisonings of the blood which have befallen our people … have led not only to a decomposition of our blood, but also of our soul.” Mein Kampf, chapter two of volume two. Again, there were plenty of contemporary examples to choose from.

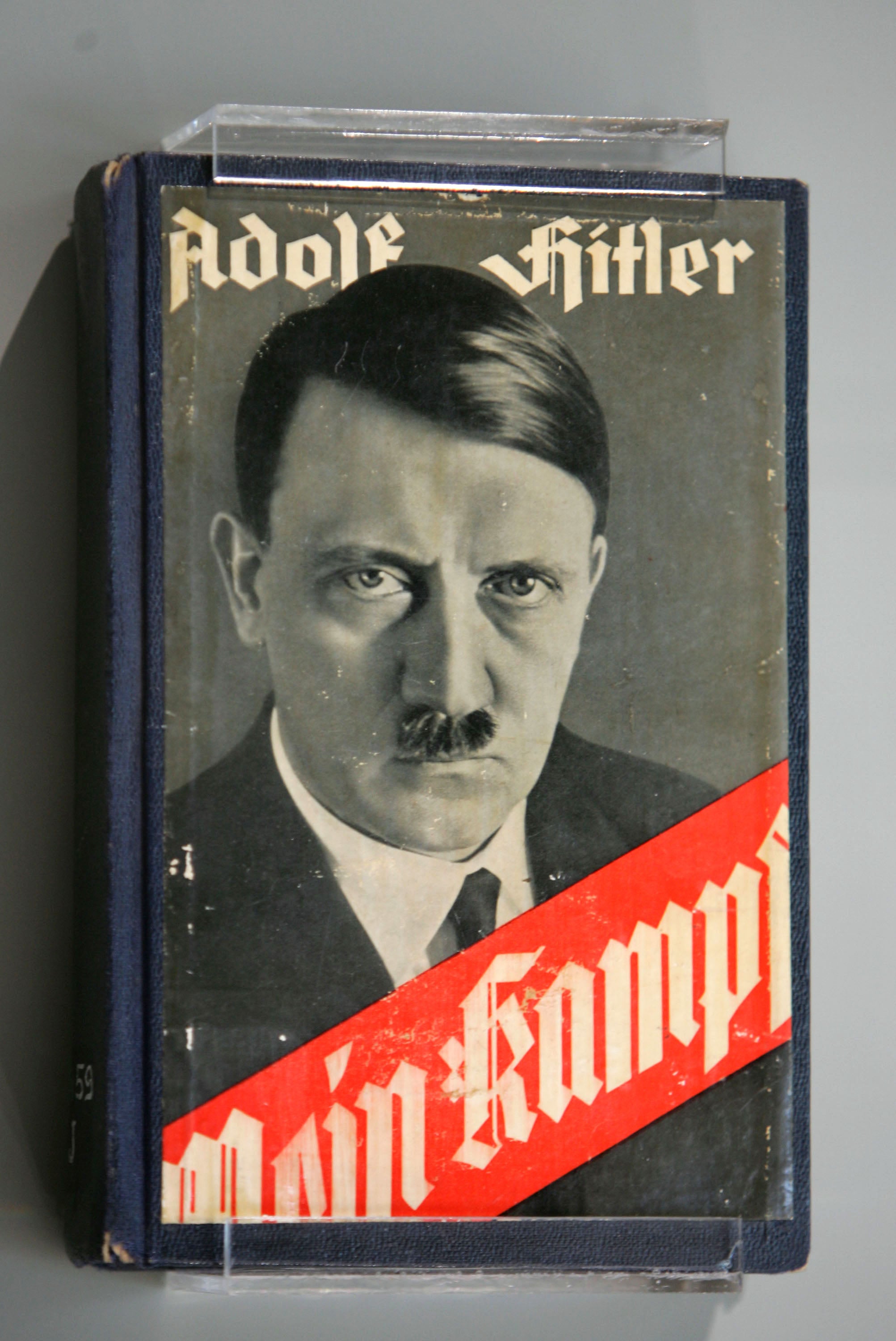

open image in gallery

Seven-hundred pages of endless distorted references to biology and race theory (Getty)

Or this, from Orban, telling an audience in July 2022 that it is acceptable for Europeans to mix with each other – but not with those arriving from outside. “We are not mixed race,” he says, “We do not want to become peoples of mixed-race.” Then stand it alongside this sentence in chapter 11 of Mein Kampf, entitled People and Race: “Blood mixture and the resultant drop in the racial level is the sole cause of the dying out of old cultures.”

And what of Elon Musk? While he was Trump’s right-hand man, he was conducting an interview with Alice Weidel, leader of Germany’s far-right AfD, in which the only criticism they could find for Hitler was that he was a “Communist”. History is clearly not their forte. Now, even as Musk is cast into the Trumpian wilderness, the X’s AI chatbot showers praise on the Fuhrer. All it was doing was reproducing much of the bile that appears on his very own social media platform.

“Mein Kampf is not special,” Strich tells me as we dart from one grisly website to the next. “There are a million different versions of the same material, the same ideology out there.”

The most intriguing aspect for me was Hitler’s loathing of the French and his respect for the English, even when expressed through suspicion. When musing about Lebensraum, about the need for Germans to find new lands in the East, he believed there was only one like-minded country with whom he could strike a deal: “For such a policy, there was but one ally in Europe: England.”

open image in gallery

Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists, addresses supporters (Getty)

In another section, he states: “No sacrifice should have been too great for winning England’s willingness. We should have renounced colonies and sea power, and spared English industry our competition.”

We know what happened in the end. Once Churchill was at the helm, Britain played a heroic role in resisting Hitler. But history has a habit of simplifying, of drawing straight lines that do not necessarily exist. It wouldn’t have taken much for the British or another country to embrace something hideous in the 1930s. And it wouldn’t take much now.

100 Years of Mein Kampf is available on BBC Sounds