The Vatican announced Sunday that its Secretary for Relations with States — the equivalent of a foreign minister — had begun a weeklong visit to India.

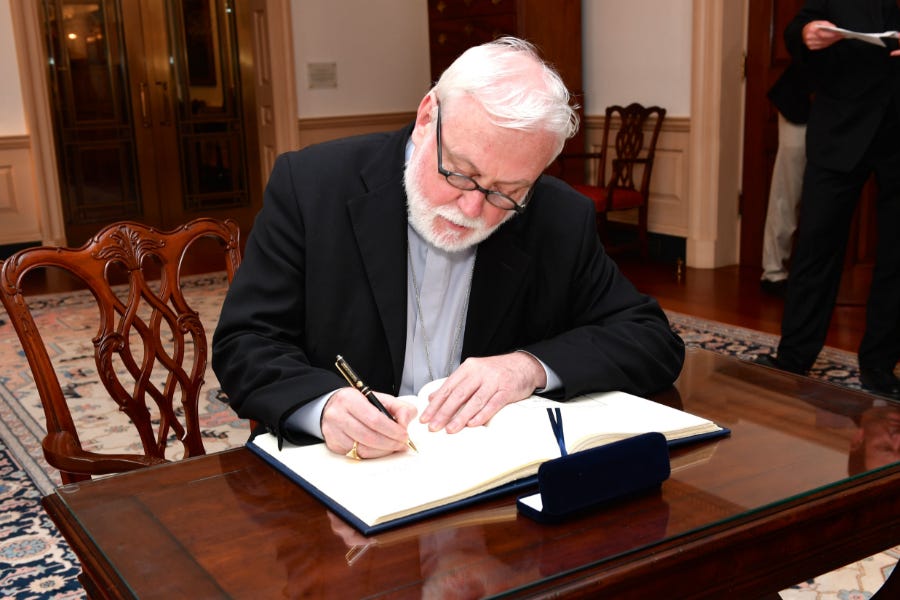

The Vatican’s Secretariat of State said July 13 that Archbishop Paul Richard Gallagher was visiting the subcontinent “to consolidate and strengthen the bonds of friendship and collaboration between the Holy See and the Republic of India.”

The diplomatic phraseology offered minimal detail. Who will the English archbishop be meeting in India? What kind of issues will he raise? And what might strengthening collaboration between the Holy See and India look like? The announcement answered none of these questions.

Nevertheless, they are pertinent because India plays an increasingly prominent role in global affairs, thanks to its growing economic might and demographic vitality. In a curious coincidence, the Holy See and the Indian government each oversee populations of approximately 1.4 billion, roughly 17% of the world’s inhabitants.

That’s not the only reason Vatican-India relations are important. Around 23 million Indians are Catholic, putting India among the top 20 countries with the largest Catholic populations. For comparison, that’s more than the Catholic populations of Belgium, Ireland, and Portugal combined.

But despite the Indian Catholic community’s relatively large size, Catholics are a tiny and vulnerable minority within a population that is 80% Hindu, 14% Muslim, and only 2% Christian.

So, what specifically might Gallagher be doing in India this week?

Gallagher’s schedule in India is not currently available, possibly for security reasons or because some appointments may not be finalized.

The big thing to watch out for is whether the archbishop secures a meeting with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who has dominated Indian political life since his initial election victory in 2014. Modi would not necessarily be expected to meet with a visiting foreign minister, so a rendezvous with Gallagher would send a signal that he personally values stronger relations with the Vatican.

Gallagher met with Modi back in 2021, when the Indian Prime Minister traveled to the Vatican and invited Pope Francis to visit India. Modi seemed to have a warm relationship with the Argentine pope. When the two men met again in 2024, at a G7 summit in Italy, they embraced and Modi renewed his invitation. Following Pope Francis’ death, Modi declared three days of state mourning in India.

A Modi-Gallagher meeting would fuel speculation about a potential papal visit to India. Currently, Leo appears to be planning just one foreign trip in 2025: to Turkey, to mark the 1,700th anniversary of the Nicene Council, a pivotal moment in early Christian history.

The competition to host Leo XIV’s second foreign visit is already heating up, with his dual homes of the U.S. and Peru arguably near the front of the queue. But India should be somewhere in the mix.

The era of globetrotting popes began with Pope Paul VI’s 1964 visit to the Holy Land. His next trip, that same year, was to India, putting the country on the papal visit map. Pope John Paul II visited India in 1986 and 1999. But no pope has visited the subcontinent since.

Slovakia, a country with just 3 million Catholics, has received two papal visits in the past 25 years (in 2003 and 2021), while India has had none. So there’s a strong case for another papal trip to the subcontinent — and Leo XIV might be open to it because he previously visited the country as head of the Augustinian order.

A visit will depend not only on Pope Leo’s diary, but also on the contending forces within India’s ruling coalition, led by Modi’s BJP. Despite the Prime Minister’s affectionate relations with Pope Francis, the BJP is a Hindu nationalist party, which insists that Hindutva, or “Hindu-ness,” is the bedrock of the country’s culture. Many Indian Catholics regard the BJP as hostile or, at best, indifferent to Christian minority concerns. Some Hindu nationalists, meanwhile, fear a papal visit could inspire conversions to Christianity.

Plans for Pope Francis to visit India in 2017 reportedly fell through after an official invitation to India failed to materialize. But things have changed since then, prompting Modi to invite the pope to visit in both 2021 and 2024.

Internal resistance undoubtedly remains, but the BJP has attempted to court Catholic voters in recent years. The party made a historic breakthrough in 2024 when it gained its first member of parliament in the southern Indian state of Kerala, which has a significant Christian population.

The BJP reportedly has its sights on the 2026 Kerala Legislative Assembly election. Traditionally, two other coalitions have dominated the state: the Left Democratic Front, led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist), and the United Democratic Front, led by the Indian National Congress. But the BJP coalition seems to believe it could break their hold and win a majority in the state.

The elections must be held before May 2026. A papal visit to India in the preceding months could therefore be an attractive prospect for the BJP. But the Vatican typically schedules papal visits outside of election periods, so it might reject this option if it were proposed.

Regardless of that specific date, the BJP seems to have a clear incentive for a papal visit that it lacked in the 2010s.

If Archbishop Gallagher fails to secure a meeting with Modi, it would be no disaster. There are other high-ranking government figures whom he could meet. The most obvious is S. Jaishankar, India’s minister of external affairs and Gallagher’s counterpart.

In any discussions with political leaders, the archbishop is likely to raise the treatment of India’s religious minorities. According to a report by the United Christian Forum, a New Delhi-based human rights advocacy group, 947 hate crime incidents took place in the 12 months after Modi’s election to a third term in June 2024. Twenty-five of the victims — all Muslims — died. The incidents were more prevalent in the 14 out of 28 Indian states ruled by the BJP.

Gallagher might also refer to the explosion of anti-Christian violence in the BJP-run state of Manipur in 2023. Sporadic clashes reportedly continue, despite the imposition of President’s Rule, or central government control, in February 2025.

Archbishop Gallagher’s weeklong visit should give him time to meet figures outside of India’s political establishment.

Encounters with Hindu and Muslim leaders could take place, perhaps arranged by the India-born Cardinal George Koovakad, the new president of the Vatican’s Dicastery for Interreligious Dialogue.

Gallagher is also likely to meet with representatives of India’s diverse Christian minority, which includes Protestants and members of the ancient Oriental Orthodox Churches.

The archbishop will also probably spend time with bishops from India’s three Catholic main Catholic communities: the Latin Church, the Syro-Malabar Church, and the Syro-Malankara Church.

The Latin Church underwent a significant leadership change with the retirement in January of Cardinal Oswald Gracias as the Archbishop of Bombay. His successor, Archbishop John Rodrigues, could be among those greeting Gallagher. Another prominent Latin Rite figure could also be on hand: Cardinal Filipe Neri Ferrão, the Archbishop of Goa and president of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences.

The Syro-Malabar Church gained a new major archbishop, or overall leader, in January 2024. Major Archbishop Raphael Thattil is currently in Melbourne, Australia, but could make it back in time to meet with Gallagher. He would have good news to report: an agreement to end the decades-long Syro-Malabar “liturgy war” appears to be holding since it took effect July 3.

Gallagher might discover that Latin Church bishops and Syro-Malabar have different perspectives on India’s political climate. Latin Church leaders tend to be more skeptical of the BJP’s overtures, because their flock is spread all over India, including in areas prone to anti-Christian violence. Syro-Malabar bishops, meanwhile, might be more open to the party because they are largely based in the more secure state of Kerala.

That said, the bishops of all three rites came together recently in support of a controversial BJP-led bill reforming the regulations governing Islamic charitable endowments.

Regardless of which Catholic leaders Gallagher ends up meeting, his visit will likely be a welcome boost for a local Church that is facing unrelenting internal and external pressures.