The Soviet occupation regime in Latvia not only repressed its inhabitants, but also imposed a number of restrictions, including on travel abroad. A permit from the Soviet security authorities was required for travel, and violating it was severely punished. Despite the risk, many did not find the idea of a future life in Soviet-occupied Latvia attractive and were prepared to take action to get through the Iron Curtain.

In the 1950s, several Latvians reached Sweden using fishing trawlers from Liepāja, and one such episode of them took place in September 1965.

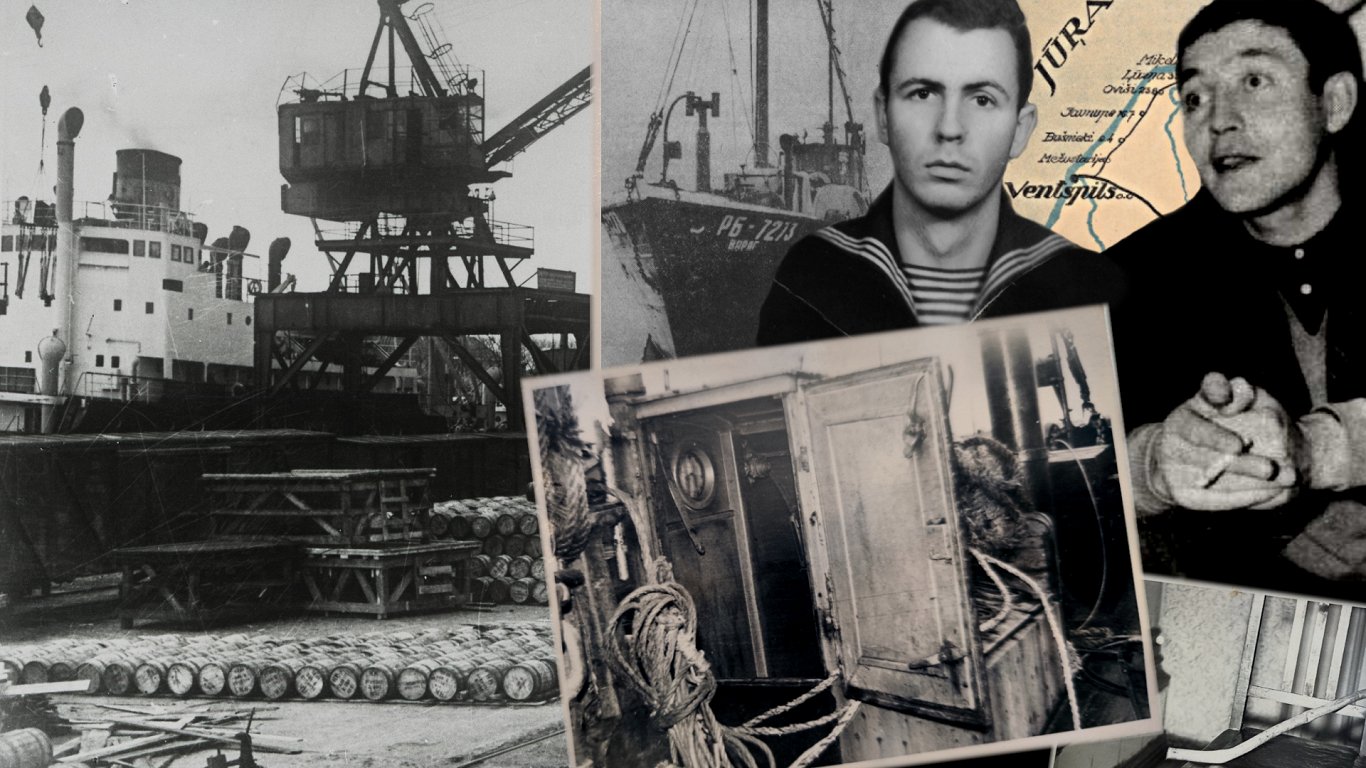

On the night of September 14, 1965, a small fishing trawler ran aground near the Swedish island of Gotland. The ship’s side was decorated with the inscription: “RB 7273 “Varjag””. This news quickly reached the news columns of many exiled Latvians, as well as the Western press in Sweden, the USA, Germany and other countries. Almost all publications reported that there were five people on board the ship. In order to get to Sweden, two crew members had hijacked the ship, while the other three members (including the ship’s captain) were locked in one of the ship’s rooms.

After the trawler was brought to safety, the two political refugees, aged about 25, were transferred to the town of Hemse, however, the Swedish security authorities initially did not provide the public with more detailed information, including the identities of the two persons. [2] After their release from temporary captivity, the other three crew members of the trawler soon returned to Ventspils.

With the trawler’s return, Soviet repressive security structures began an investigation into what had happened.

Escape plan and its implementation

As it turned out, there were five people on board the trawler: captain Tālivaldis Rozentāls (born in 1933), assistant captain Valdis Svarāns (born in 1941), mechanic Visvaldis Burkovskis (born in 1933), assistant mechanic Inārs Rendinieks (born in 1939) and a stowaway with sailing experience, Jānis Tēbergs (born in 1943).

Photo: Laikraksts Latvija, Nr. 36, 1965.

According to the testimonies of three crew members of the fishing trawler “Varjag”, the events unfolded according to the following scenario: in the early morning of September 13, the crew members arrived on the trawler at the port of Ventspils. Along with them, officers of the Latvian SSR border guard also boarded the ship to inspect it before the planned voyage. On September 13, at approximately 5 in the morning, the trawler set off on the planned fishing trip in the Baltic Sea.

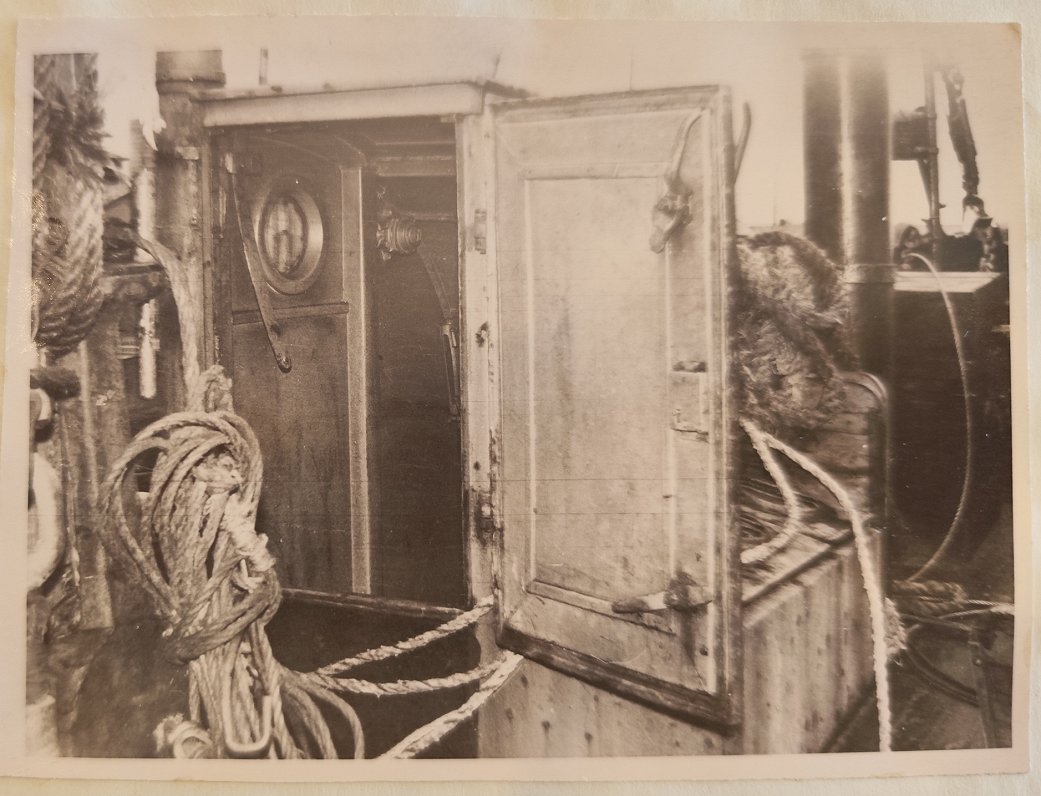

After a short time, the ship’s captain T. Rozentāls handed over the command of the trawler to his assistant V. Svarāns, but himself went to rest in the cabin, where crew members V. Burkovskis and I. Rendinieks were already located. At around 6 a.m., Rendinieks noticed that the door to the room was closed.

As it turned out, Svarāns had locked them in, at the same time changing the ship’s course and heading for the Swedish island of Gotland.

When the imprisoned crew members tried to open the door, Svarāns fired three warning shots from a gun. The imprisoned crew members called on Svarāns to release them and change the ship’s course back to Ventspils, but received a negative response. On September 13, at around 10 p.m., the “Varjag” ran aground near Gotland.

To attract the attention of the Swedish coast guard, Svarāns fired three flares. Soon, a Swedish pilot ship approached the ship and pulled it off the ground. According to the trawler’s crew, they noticed the unknown person (presumably J. Tēbergs) on deck shortly before the pilot ship arrived. The stranger, dressed in an oilskin jacket, had a black beret on his head and long sailor boots.” [3]

Swedish sailors brought the stranded fishing trawler to the port of Ronnehamn. Svarāns and Tēbergs disembarked and asked the Swedish authorities for political asylum, while the imprisoned crew members of the trawler were released after clarifying the circumstances of the incident and providing various explanations, and allowed to return to Ventspils.

The trawler’s mechanic V. Burkovskis later testified to KGB investigators that an interpreter asked whether the crew of the ship did not want to stay in Sweden, as two crew members had expressed such a desire. The rest of the crew rejected this offer.

The “Varjag” returned to the coast of occupied Latvia on the morning of September 15 with three crew members. Despite the insistent requests of the Soviet authorities, the Swedish authorities refused to extradite the two refugees and allowed them to settle permanently in Sweden.

It follows from the criminal case materials that Svarāns hid his associate Tēbergs in one of the trawler’s compartments and covered him with coal, but in order not to suffocate, he breathed through a metal tube prepared for this purpose.

Who were the daring escapees?

Captain’s assistant Valdis Svarāns studied at the Liepāja Maritime School under the Latvian SSR Latvian Fish Production Industry Administration, which he successfully graduated from in less than five years, obtaining the qualification of a helmsman for a marine transport manager. In parallel with all the necessary subjects (navigation, geography, ship construction and management, etc.), he also mastered English at a good level. In the first half of the 1960s, Svarāns also worked in the People’s Voluntary Public Order Guard Unit in Liepāja.

Almost immediately after completing his studies, the future shipmaster was drafted into the Soviet Army and sent to the Kaliningrad region, where he underwent a month and a half of military training. Upon returning to his native Ventspils, Valdis began working in the fishing cooperative “Sarkanā bāka”.

Colleagues and relatives called Valdis a hardworking and decent person. The captain of the fishing trawler “Varjag” T. Rozentāls described Svarāns positively, and moreover, he had not observed any “anti-Soviet stance” in him. As Svarāns’ mother said, in his free time Valdis was interested in literature, including works by foreign authors and Western music. Representatives of the Liepāja Maritime School also highlighted Svarāns’ good personal qualities – helpfulness, dedication, tact, kindness, etc., including noting his good results in English language courses. It should be mentioned that Svarāns actively participated in editing the English-language wall newspaper of the maritime school students.

The second participant in the escape operation, Jānis Tēbergs, was born in Riga and studied at the Riga Food Industry Technical School. As Tēbergs himself indicated in his autobiography, in 1959 he realized that his chosen profession did not interest him, and began working at the Sloka Pulp and Paper Plant.

In parallel with this, he studied at evening school in Riga. The next job in Jānis’s life was the position of sailor and mechanic at the River Transport Board. In 1962, he went to the Far East to gain work experience, but soon returned and resumed work at the Sloka Pulp and Paper Plant, and a little more than a year before his adventurous trip to Gotland, he joined the All-Union Lenin Communist Youth Union (VĻKJS). Less than three weeks before leaving for Sweden, he got a job as a sailor in the fleet of the Sea Fishing Port.

The human resources department of the Sloka pulp and paper mill gave a less positive opinion about Tēbergs. They pointed out that although Tēbergs generally fulfilled his work duties, he was fond of drinking and was often late for work, there were also problems in the family, etc. This information was also confirmed by other questioned Tēbergs family members and work colleagues.

Investigation process

After the incident, the Soviet authorities took appropriate procedural actions. As part of this, employees of the State Security Committee (KGB) inspected the ship, questioned its crew and the relatives of the two refugees, as well as acquaintances, and searched their homes. After inspecting the trawler, Soviet investigators found old blue trousers, a bent metal pipe, rubber boots, a safety vest, a signal pistol, a homemade 5.6 mm pistol, a map of the island of Gotland, two unopened bottles of “Kristal” vodka and other items, while various personal belongings (documents, photographs, etc.) were seized from the homes of Svarāns and Tēbergs, as well as 20 pistol cartridges.

Investigators also determined that Tēbergs was actually Svarāns’ cousin. [4] It was also revealed that Tēbergs arrived at Svarāns’ place in Ventspils on September 8 and stayed with him until the fateful voyage to Sweden, and that the escape operation had been carefully planned.

V. Svarāns’ mother suggested to the KGB investigators that it was Tēbergs who had initiated the escape, and as far as she knew, Tēbergs’ uncle Krastiņš was living in Sweden at the time, and had also visited the Latvian SSR in 1962 or 1963. In addition, Tēbergs’ mother had also gone to Sweden. The Latvian press in exile also reported in the autumn of 1965 that one of the escapees had a relative living in Sweden. None of the family members knew anything about the escape plans of the two young men.

The Soviet repressive authorities initiated a criminal case regarding the incident and, in accordance with Article 78 of the Latvian SSR Criminal Code, charged V. Svarāns and J. Tēbergs with illegally crossing the USSR border without a passport or permission from the relevant authorities. This article provided for imprisonment from one to three years. In the event of their return, both defectors were to be immediately arrested.

Soviet investigators intercepted a letter sent home by V. Svarāns from the Swedish city of Eskilstuna in January 1966. In it, he talked about the nuances of learning the Swedish language, the prices of various goods, especially highlighting the high cost of tobacco and alcohol products, as well as the high costs of housing and fuel. Valdis emphasized that he was satisfied with life and did not yet know anything about his future plans.

USSR note and termination of the case

Less than a week after the Latvians arrived on the island of Gotland, the USSR submitted a diplomatic note to Sweden demanding the immediate extradition of Svarāns and Tēbergs. However, the Swedish Foreign Affairs Commission had granted permanent residence permits to both refugees. Although the USSR diplomats indicated that Svarāns and Tēbergs had committed a criminal offense by hijacking a fishing trawler, the Swedes stated that they had taken this circumstance into account.

Svarāns and Tēbergs began working “in a factory near Stockholm”. In the following years, their names occasionally were mentioned by the Soviet authorities as examples of criminals and traitors, Meanwhile Svarāns started a family and settled in Sēdertēlē near Stockholm, while Tēbergs lived in Vēnesbōrja.